Originally presented as a lecture at Klezcadia festival in Victoria, B.C., June 2024.

The Zimro Ensemble was a short-lived chamber music sextet of conservatory-trained Russian Jewish musicians which left on a world tour from Petrograd in 1918. Crossing Russia, Siberia, China, Southeast Asia, and the United States over 3 years, they disbanded in New York in 1921. Professing a cultural Zionist mission, the group claimed to be touring to raise funds for a temple of Jewish culture in Palestine; its rarely-used official name was the Palestine Chamber Music Ensemble “ZIMRO.” That temple was never built, and at the end of their tours the members went their separate ways and became professional musicians in the US. My focus here will be on the few months they spent in the Dutch East Indies in 1919, waiting for a US visa and performing modernist Jewish music or classical music for audiences in elite colonial spaces. During those months, in a place with few Jews and even fewer Zionists, their mission was mostly put on hold. Instead, during that time they were living as European gentlemen in a colony undergoing radical social change, a place with deep racial inequality where Europeans were less than one percent of the population but ran everything.

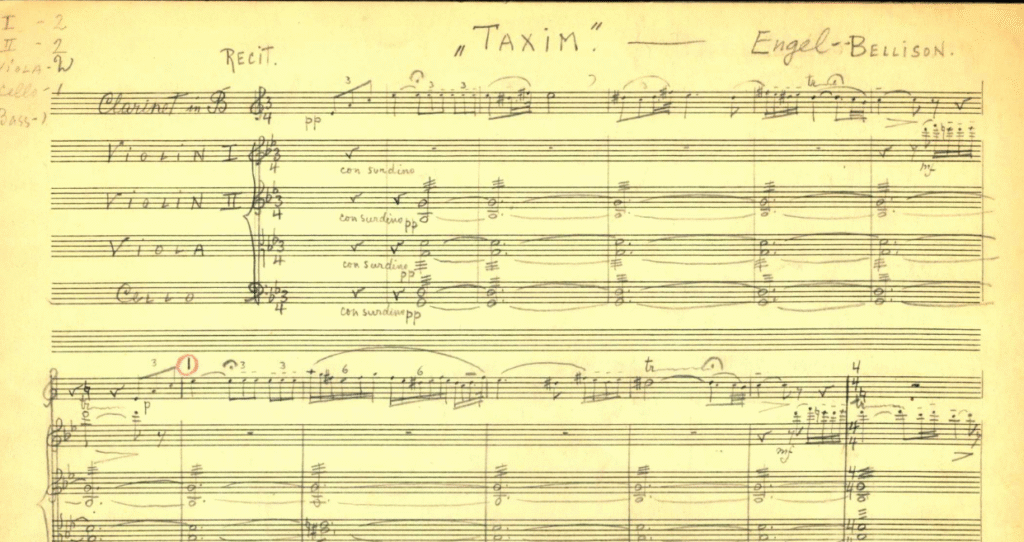

The Zimro Ensemble emerged from the St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music, a nationalistic art music movement which contained various contradictory strains of socialism, elite Russian culture and Zionism.[1] The music Zimro played during their few years of existence was a mix of standard classical works—Mozart, Chopin, Tchaikowsky—and newer works from that Society for Jewish Folk Music milieu, which often took klezmer melodies, cantorial music or Yiddish folk songs and adapted them into “elevated” forms. The founder of Zimro is generally agreed to be clarinetist Simeon Bellison,[2] who had studied at the Moscow Conservatory. The cellist Joseph Cherniavsky also took a leading role in organizing and promoting the ensemble during its existence. The other members were also trained in Russian, German and Austrian conservatories, and some (like Cherniavsky) came from klezmer families.

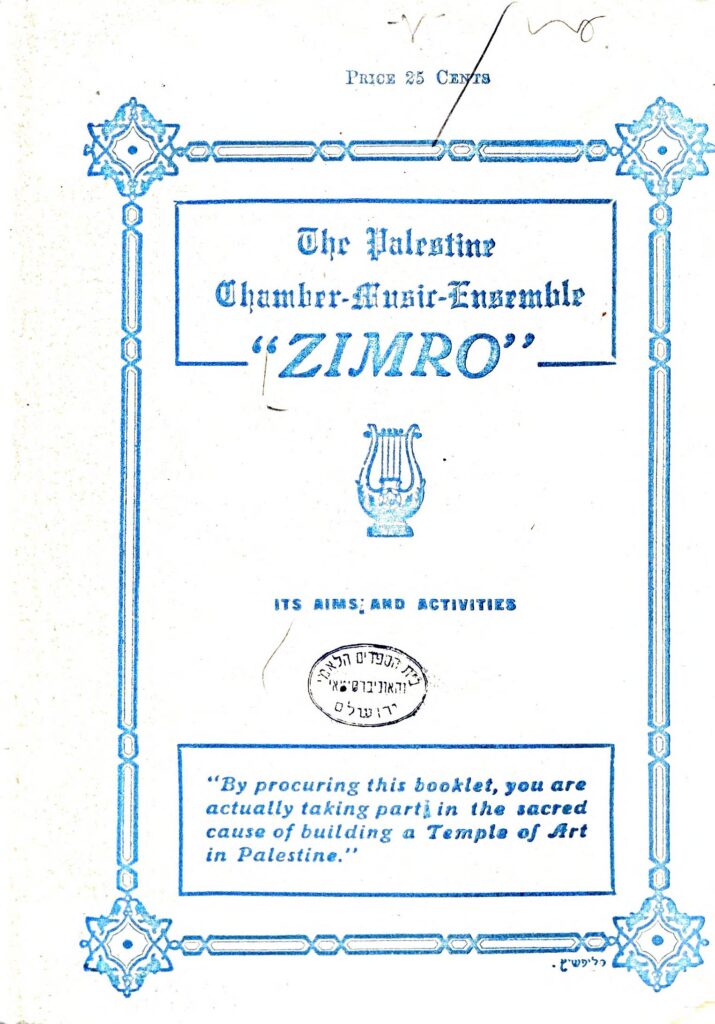

The stated mission of Zimro was spelled out in a bilingual English-Yiddish booklet they published in New York in around 1920.[3] Per the booklet, Zimro embarked on its tour with three goals:

1) To propagate Jewish Folk Music artistically cultivated. 2) To collect means by subsidy and percentage from income of concerts, for the fund which the “Zimro” Ensemble established for the purpose of building a Temple of Art in Palestine. 3) To unite all Jews, who are active in the field of art and literature, in one common bond under the name of “Omonuth” (Art), in order that they may contribute potentially to the revival of the Jewish Nation and cooperate in the development of Jewish Art in Palestine.[4]

According to the booklet, branches of art societies would be established in cities around the world, with Jewish artists using it as a basis to build “a vital, natural and constantly streaming fountain of material means to finance our institutions in Palestine.”[5] The bombastic and triumphant rhetoric of this scheme stands in contrast to the group’s slightly bitter dissolution or their portrayal in the non-Jewish press as talented but underpaid musicians who were driven out of Russia by circumstance. I have no idea how much the members of the ensemble originally believed in their mission, or at what point between being on the back of a wagon in Siberia and performing in Carnegie Hall that they abandoned it.

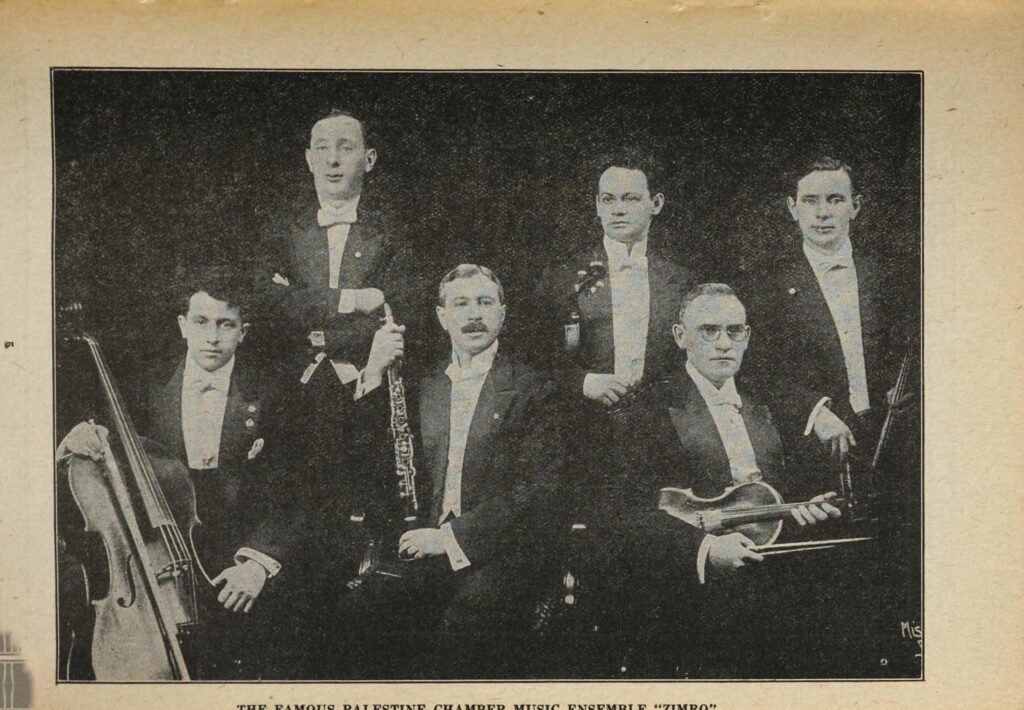

The 1920 booklet states that Zimro is made up of these six men: Simeon Bellison, clarinet; Jacob Mistechkin, first violin; Gregory Besrodny, second violin; Nicolas Moldovan, viola; Joseph Cherniavsky, cello; and Leo Berdichevsky, piano.

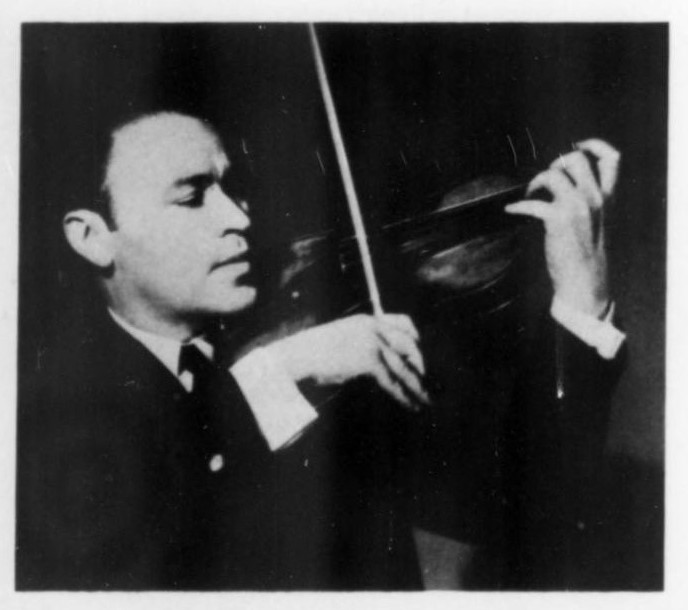

Before they arrived in the US, the lineup was a bit different. Besrodny, the second violinist, didn’t join Zimro until New York. While still in Russia, they may have had a different pianist called Nachutin, and they definitely had a different second violinist called Michael Rosenker,[6] who performed during Zimro’s journey across Siberia and their first stop in China.[7] Rosenker later become a well-known violinist and concertmaster in the US. It seems that the pregnancy of his wife Reisa made him decide to stay in Asia and not to embark on the journey across the Pacific (and to Palestine after that); he toured in China and then in the Indies with the Moscow Trio for a lot longer than Zimro did.[8]

Elfrieda Bos, first violinist Jacob Mestechkin’s wife and the first woman to play in the St. Petersburg Symphony,[9] was second violinist during the Dutch East Indies tour and the second tour in China. Lara Cherniavsky, a pianist, arranger and wife of cellist Joseph Cherniavsky, also accompanied Zimro on their entire tour along with their infant son, although she doesn’t seem to have performed with them in Asia. During their tour, the Cherniavskys also hired a nurse from Irkutsk, Marie Timofeeva, to accompany them.

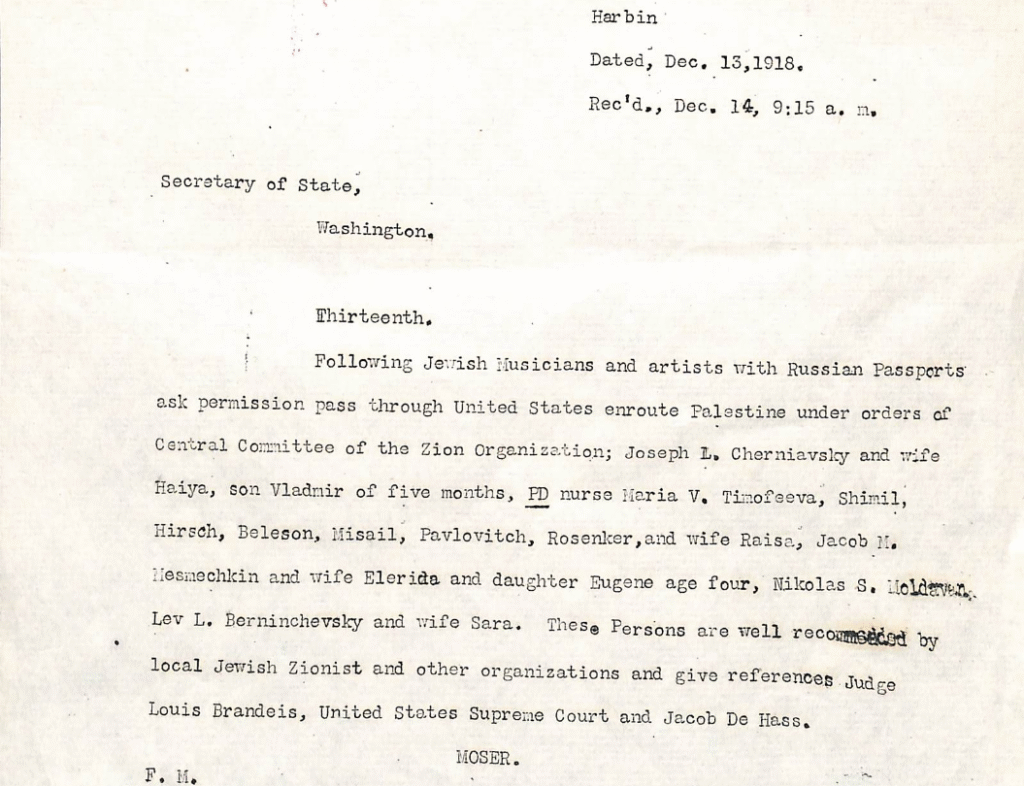

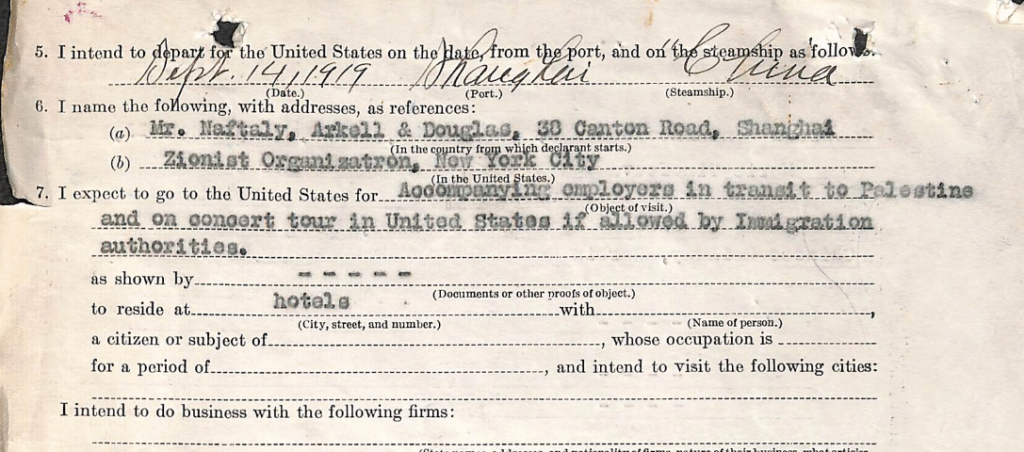

Having left Petrograd in the fall of 1918, Zimro crossed Siberia and ended up in Harbin, China by late November 1918.[10] It was from the American consulate there that they and their families made an application for a US visa in mid-December.[11] Harbin, a city on the Soviet-Chinese border originally built by Russia, just saw a social revolution put down by Chinese troops and then a huge influx of White Russian refugees. So, Zimro’s concerts there were well attended and, according to their booklet, very lucrative as well. While they continued on to Shanghai from there, their visa application made its way around the US, where it would eventually be rejected.

I’ve been aware of the Zimro Ensemble’s layover in Java for a few years now, and I read somewhere that their visa issues were related to a quarantine from the Spanish Flu, which was raging in both the United States and the Indies at that time. In Java, it was surging in the fall and winter of 1918, at the moment when the members of Zimro were still in Siberia and China.[12] It was so severe in Java in November 1918 that fields went untilled and offices were empty due to widespread illness.[13] However, after looking at the US visa correspondence for the Zimro members, and what was going on with US immigration at that time, it doesn’t seem that Spanish Flu was the main reason for their troubles. Instead it was resurgent US nativism, as manifested in the Immigration Act of 1917 and the red scare, which put limits on immigration from most of Asia, including the Soviet Union east of the Urals.

In the December 1918 letter from the American Consul to his superiors, he noted that “These persons are well recommended by local Jewish Zionist and other organizations and give references Judge Louis Brandeis, United States Supreme Court and Jacob De Hass.”[14] I’m guessing that some local notables they met during their tour told them to give these two names, including a US Supreme Court justice, as their references.

Further documents in February 1919 show that agents were sent to interview Justice Brandeis, who admitted he hadn’t heard of these musicians, and Jacob De Hass, secretary of the Zionist Organization in New York, who was in Europe at the time.[15] De Hass’s assistant, Charles Cowen, was interviewed and admitted he also hadn’t heard of the musicians.[16] Because no one could vouch for them, the department replied to Harbin in mid-February that the visas should be denied.[17] Zimro would have continued on the the United States much sooner if they had been granted a visa.

While waiting around in Shanghai, Zimro were performing and mingling among the upper class Jewish and English society there, where some wealthy art patrons funded their concerts. It was there that they met Mario Paci, who proposed their side tour to Java[18] and wrote to some notables in Java to suggest bringing the group.[19] Paci was an Italian-born pianist and conductor who had spent much of the early twentieth century in the Indies and later became an important figure in classical music education in Shanghai.[20]

In a French-language letter to his wife in January, Paci mentioned the “Sextuor Russe” (meaning Zimro) and the Moscow Trio (Rozenker’s other group).[21] He described the sad sight of their third concert in Shanghai, which was a great artistic success performed to a nearly empty hall. I should mention, in the interest of clarifying the racial attitudes of the time, that Paci also wrote racist comments in the same letter. He was praising his Iraqi Jewish patron in Shanghai and insisted that he was a real gentleman and nothing like the Arabs in Surabaya, the city in Java where he had lived before. Whether the members of Zimro shared such attitudes, I don’t know. But they would soon be leaving China to enter the highly racist world of the upper class Dutch East Indies.

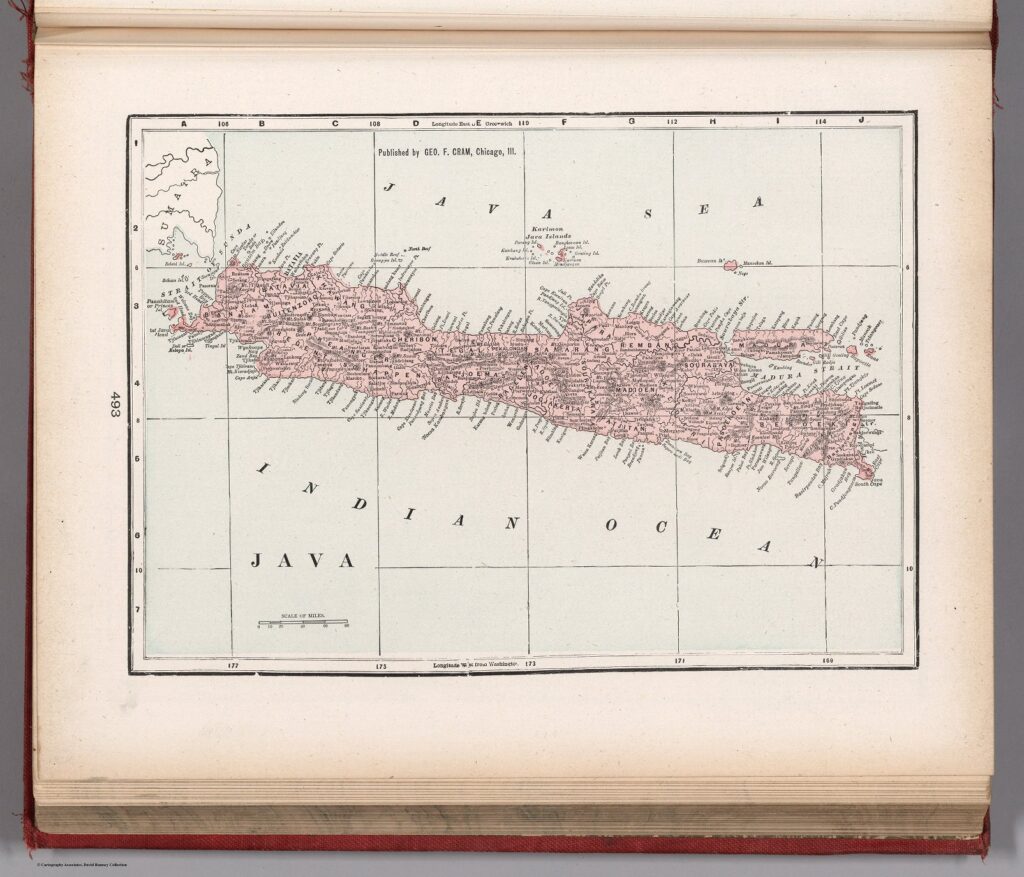

Before describing the tour in Java and Sumatra, I’ll give a bit of historical context. The Dutch East Indies, today called Indonesia, was under Dutch control for centuries but only started to see industrialization and mass European immigration in the early 20th century. During and after World War I, there was radical social change and labor unrest. Many more Indonesians began to receive a European education than ever before and the Indonesian National Awakening became a mass movement for the first time.[22] If you want to read a very accessible book on European life there at that time, Kees van Dijk’s The Netherland Indies and the Great War (from 2007) is available as a free ebook. For a history of the rise of the Indonesian anti-colonial movement, I recommend Takashi Shiraishi’s An Age in Motion: Popular Radicalism in Java, 1912-1926, published in 1990, which is a bit harder to find, but is a great read.

In that era, despite being more than 98% of the population of the Indies, native Indonesians had the lowest legal status. At the top of the racially stratified legal system were Europeans, which also included mixed-race people with European and native ancestry (Indo people). In the middle were so-called Vreemde Oosterlingen (Foreign Orientals), which included Chinese and Arabs; and at the bottom were so-called Inlanders, which included all local Indonesian ethnic groups (Javanese, Batak, Minangkabau, and so on). The latter two categories were not citizens and had few political rights. Urban Indonesians worked as coolies, domestic servants, factory workers and in the lowest rungs of the civil service.[23]

In Surabaya, where Zimro first performed, it was only in the 1910s that Indonesians were even allowed to wear shoes or jackets in public, to sit on chairs instead of on the floor, or to speak in Dutch to Europeans. These changes resulted from their entry into the industrial workforce and increased social mixing.[24] Previously all of those things were formally forbidden as part of the system of racial differentiation. In some places the local aristocracy were exceptions to this, and lived luxurious lifestyles as part of the colonial system. Only strict social control, censorship, police violence and mass arrests kept this system of minority rule going.

It is in that context that the members of Zimro arrived; they probably encountered Indonesians more often as servants than as an audience. Their Russianness or Jewishness likely didn’t set them apart much from other Europeans, except in the context of the red scare which I will discuss later. The Dutch system was by this time very used to incorporating newly arrived Europeans into their system of domination. They arrived from overseas, worked a few years, and went back, while having Indonesian servants or working in businesses that brutally exploited them. The nationality or personal beliefs of those Europeans wasn’t particularly important to how this system worked.

As for the classical music world in the Indies, it was also racially divided. Not intentionally, but as a byproduct of the whole system where natives were formally excluded from European spaces and institutions. Western musical education among native Indonesians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was limited to a select few who had received a European education. These mainly came from aristocratic families or were the children of colonial government employees. In the 19th century it was mainly in missionary schools, whereas in the early 20th century it was part of the training of Indonesian students in native teacher training schools (kweekschools). Many of these kweekschool gradutes became the composers and intellectuals of the early nationalist movement in the 1920s.[25]

By World War I, some educated young Indonesians did embrace European music in the same way they started to wear western clothing and publicly speak in Dutch: to assert themselves as deserving equality in the modernizing world. The word of the day was kemadjoean, renewal or modernization, and gerakan, movement. These youths played marches and and danced polkas and waltzes in their clubs.[26] Other Indonesians embraced Hawaiian-influenced kerontjong bands and other local fusion genres played with Western instruments. Indonesians also performed and enjoyed a wide variety of indigenous musical forms, including Gamelan ensembles, Tembang Sunda, and so on. But at the level of elite classical music Zimro were performing in, Indonesians were still very much excluded. Elite European buildings where such music was played, which included social clubs, hotels, restaurants, theatres and concert halls, often had formal or informal rules to keep them out, not to mention that their cost was far beyond the usual wages paid to native workers. Elite Muslim Indonesians, who might have been the few who could have afforded it, also rejected such spaces because gambling, pleasure-seeking and alcohol consumption took place in them.[27]

Europeans in the Indies, on the other hand, formed a growing market for music and musicians.[28] Urban bourgeois Europeans in particular, whose households were run by Indonesian servants, had plenty of time to devote to artistic and charitable pursuits.[29] There were art circles, chamber music clubs, and music and theatre foundations in most cities with an established European presence. These would have been the primary audience for the concerts of Zimro and other European groups touring in Java.

In Dutch colonial newspapers on the Delpher database I found dozens of articles about Zimro’s tour; I couldn’t find a single article about it in the Malay language newspapers read by Indonesians and Chinese Indonesians on equivalent sites like CRL’s Southeast Asian Newspapers.

Colonial Dutch newspapers are also a problematic and unreliable source. The Dutch press was supported by the plantation economy and regularly published racist content against Indonesians and justified violent repression against them. The worst offenders here are probably de Preanger-Bode from Bandung and Het Nieuws van den dag from Batavia; some other papers like de Locomotief in Semarang and Soerabaiasch Handelsblad in Surabaya had a more liberal outlook, despite still being invested in the colonial system. These papers often engaged in wars of words about politics and society, which sometimes even came up in the coverage of Zimro’s tour. By the way, when I give quotes from these papers I’ve translated it from Dutch, but I’m not a fluent reader of it, so please excuse any mistakes.

As an aside, a rare Indonesian figure who was interested in the classical musical history of that era was composer and cellist Amir Pasaribu, son of a government functionary from Sumatra and graduate of Dutch-language schools. (He’s also a distant relative of a friend of mine, whose father met him once as an old man in Suriname, where he lived much of his life in exile.)

Born in 1915, Pasaribu was too young to experience this era of music firsthand. But among his early teachers in the 1930s were expatriate Europeans, including a Russian cellist Nicolai Varvolomeyev. During the 1940s and 50s, at a time when Indonesia was newly independent and turning away from Dutch culture, Pasaribu interviewed older musicians about their memories of the early 20th century.

According to one of Pasaribu’s articles, several waves of Russian classical musicians appeared in Java during the late colonial era. After an earlier wave of Italian musicians, a group of Russian conservatory music instructors arrived in 1915; members of the Moscow Trio (who ex-Zimro member Rozenker played with) settled in Solo as music teachers soon after; an opera troupe led by Feodorof in 1920, and another assorted group of Russian musicians who came down from Shanghai in 1925, including Pasaribu’s own teacher Varvolomeyev; and finally Doblowotsky’s balalaika orchestra in 1930.[30] Today, with wide access to digitized versions of colonial newspapers, we can add to that list a much larger number of touring Russian acts who came and went during the 1910s and 1920s.[31]

As for the Jewish population of Java, today it is almost nonexistent, but 100 years ago it was also a very small population without many communal institutions. In 1919 there were probably 2000 Jews in the Indies, with three quarters living in Java.[32] The biggest group was in Surabaya, a bustling port city on the eastern coast of Java where Zimro came to play their first concert, with small communities in the other big cities: Batavia, Semarang, and so on.[33] Before 1910 Jews generally came alone, intermarried and assimilated, but with urbanization and modernization in the 1910s, a small established Jewish community gradually took shape.[34] In 1919, aside from Dutch and German Jews, most were English-speaking Jews from Cochin, Aden or Iraq, with some from Singapore and Malaya; Eastern European Jews only started to arrive as a group in the late 1930s,[35] which helped to swell the number of Jews in Surabaya to 3000 in 1941.[36]

According to some accounts, the European and Baghdadi Jews didn’t interact much in Java, because of cultural and language barriers.[37] I’m also not sure how members of this diverse Jewish population were treated in the racial hierarchy. Certainly European Jews were treated as Europeans, but I’m not sure if the Baghdadi Jews had the same status as other Arabs (so-called Foreign Orientals). If they were British subjects, they may have had a special status.

So, Zimro arrived at a time when there was barely a local Jewish community. They probably didn’t encounter many other Russian Jews. They likely didn’t meet many Zionists either. There was an organization, the Netherlands Indies Zionist Union (Nederlands-Indische Zionistenbond), which had been recently founded and which took donations for their Temple of Culture cause at a few of Zimro’s concerts, but by all accounts it was a fairly marginal organization. As I said before, I actually think Zimro’s main audience on their tour were Dutch or other Christian Europeans who saw them as Russians and saw the Jewish aspects of the performance, or their political programme as secondary, if they were aware of it at all.

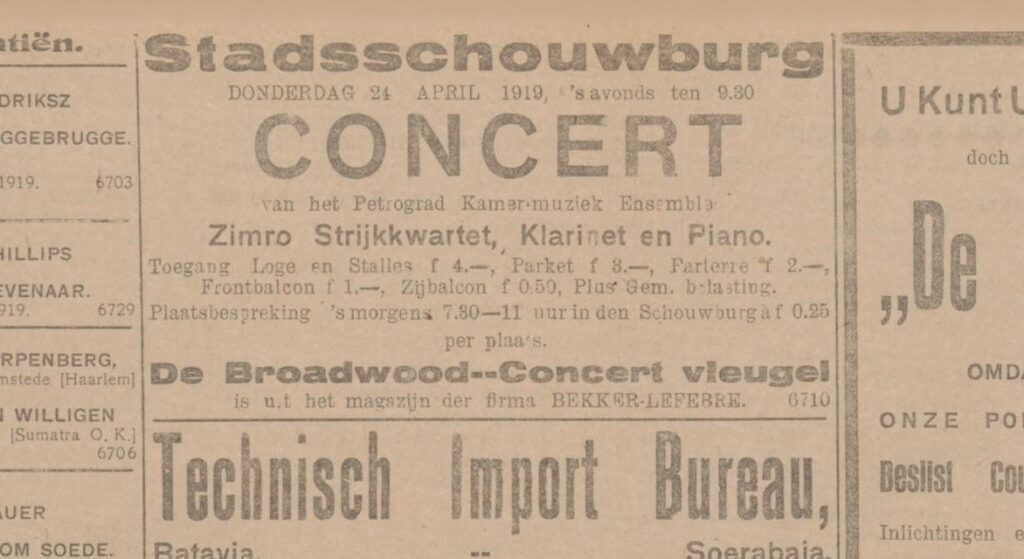

Next I’ll talk about Zimro’s arrival and first tour in Java, which took place from late March to early May 1919.

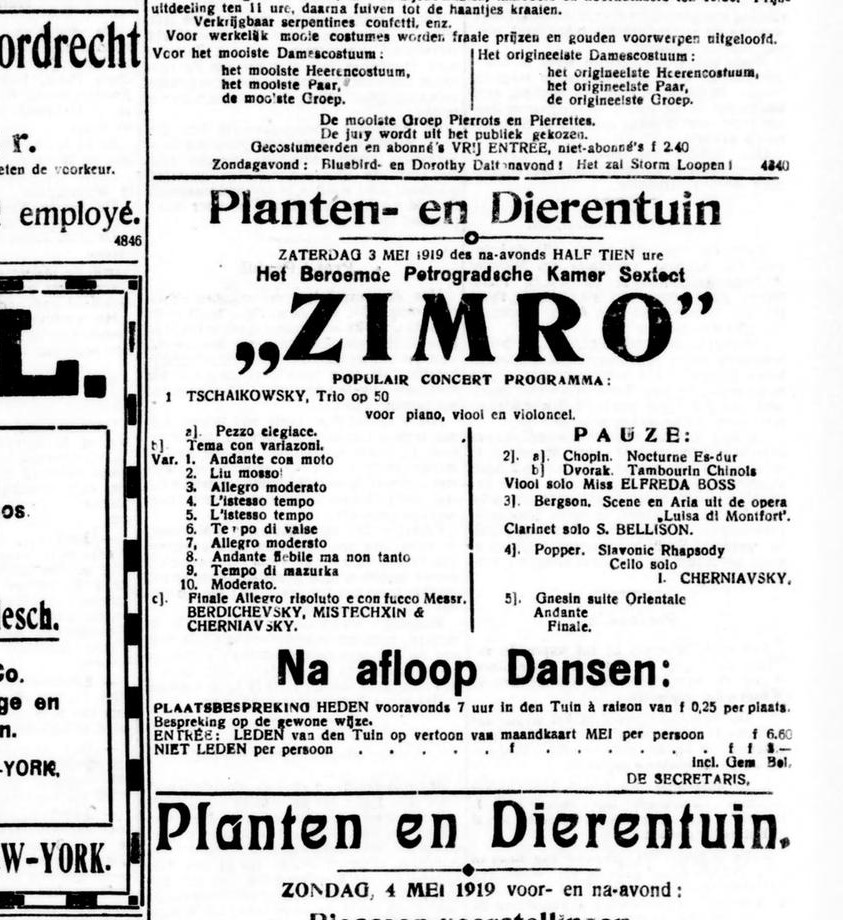

Probably because of the efforts of Mario Paci, newspapers in Java already knew that Zimro was on its way by March 12th, when an article appeared in Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad noting that a group called the Petrograd Sextet was on its way from Shanghai and hoped to play the city opera house on the 23rd.[38] I’m not sure if that concert took place. Like many articles about them in the colonial press, the writer did not seem to understand or care that it was meant to be a specifically Jewish or Zionist ensemble, and described them as yet another expatriate Russian group turning up in the Far East. Most of Zimro’s concerts featured Russian and other European classical music, rather than their specialized Jewish repertoire, which probably added to this perception. Newspapers called them the Zimro-Sextet, Petrogradsche Kamer Sextet Zimro, or most often simply de Zimro’s.

As for Indonesians, they are barely mentioned at all in this newspaper coverage (maybe twice across more than a hundred articles about Zimro). But of course they were there, so we’re missing part of the story. As Europeans in the Indies did not consider Indonesians their equals, they were not considered a partner worth mentioning in the performance and discussion of European art culture, even though it couldn’t happen without them.

Surabaya – March 29

The earliest concert I could find clearly documented was in Surabaya on March 29th, 1919. Zimro performed for the Surabaya Kunstkring (art circle), where Peci had performed before.[39] Surabaya, then as now, was a huge, diverse and bustling city in East Java, second only to the capital Batavia (which is now Jakarta). As I mentioned, it was the main centre of Java’s Jewish population—mostly English and Arabic-speaking Baghdadi Jews—as well as Muslim Arabs, who were mostly from Yemen. It also had many Europeans, a huge Chinese population, and the native majority of Javanese and Madurese. It was also a hotbed of anti-colonial radicalism; future Indonesian president Sukarno was a student in a Dutch school there in 1919.

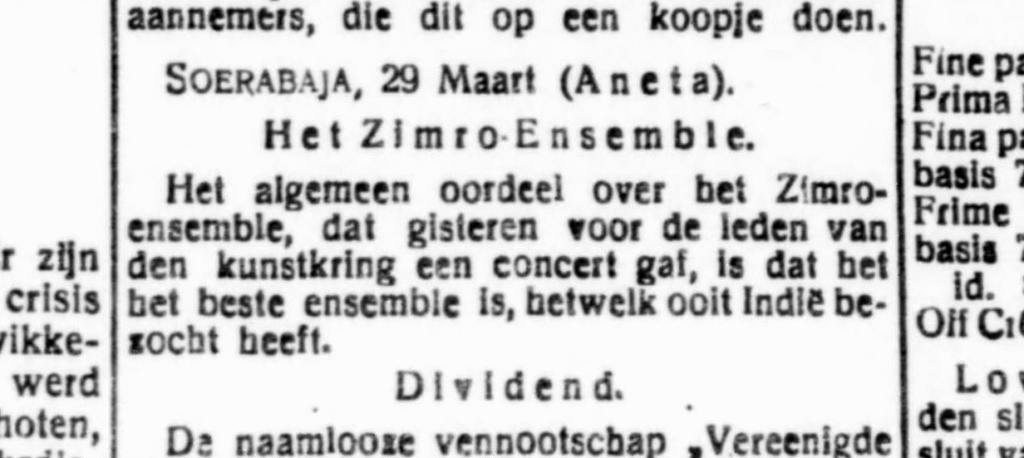

In this first concert, Zimro were already impressing audiences. A short review of Zimro’s concert sent around on the wire service ANETA (seen below) called Zimro the best ensemble that had ever played in the Indies.[40]

Surakarta – April 12

From Surabaya, Zimro set off towards the west, probably by train. Their next concert I could find was at the Harmonie society in Surakarta in central Java on April 12, at the invitation of the Kunstkring there.[41] Surakarta, known informally as Solo, is a city in central Java known for being the seat of classical Javanese culture and was ruled by a hereditary monarch. Zimro’s concert there received a stellar review in de Locomotief. The paper’s Surakarta correspondent wrote that that they considered it to be one of the first true chamber music performances in Java, that the performance of Brahms was so subtle and showed deep unity of thought. The reviewer added, “It is a pity that the room was only very sparsely occupied. Presumably a result of too little advertising.”[42] From there the review turns to the complaints common in these reviews:

Just a few more comments in connection with the concert. Can’t the billiard room be closed for future such classical concerts? The tapping of billiard balls was extremely annoying and appears to be a pointedly rude, firstly towards the artists and secondly towards the audience. […] The walking back and forth between the attendants and the occasional opening of water bottles and the like is also extremely disruptive.[43]

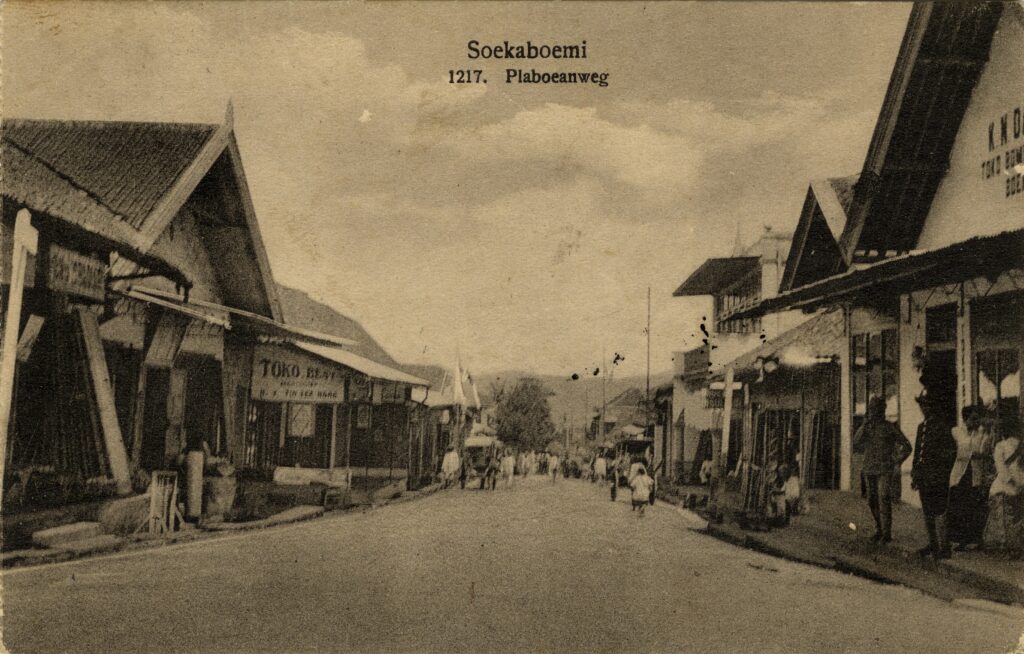

Sukabumi – April 19-20

The next stop on their tour was in Sukabumi, a small city in the tea plantation part of West Java with an almost entirely Sundanese population, but also a small European and Chinese population. I didn’t find out much about the concert, but the ANETA wire service reported on it:

The Zimro sextet gave a concert on Saturday for a grateful but small audience. On Sunday it expected more and gave another concert, but then for only twenty people.[44]

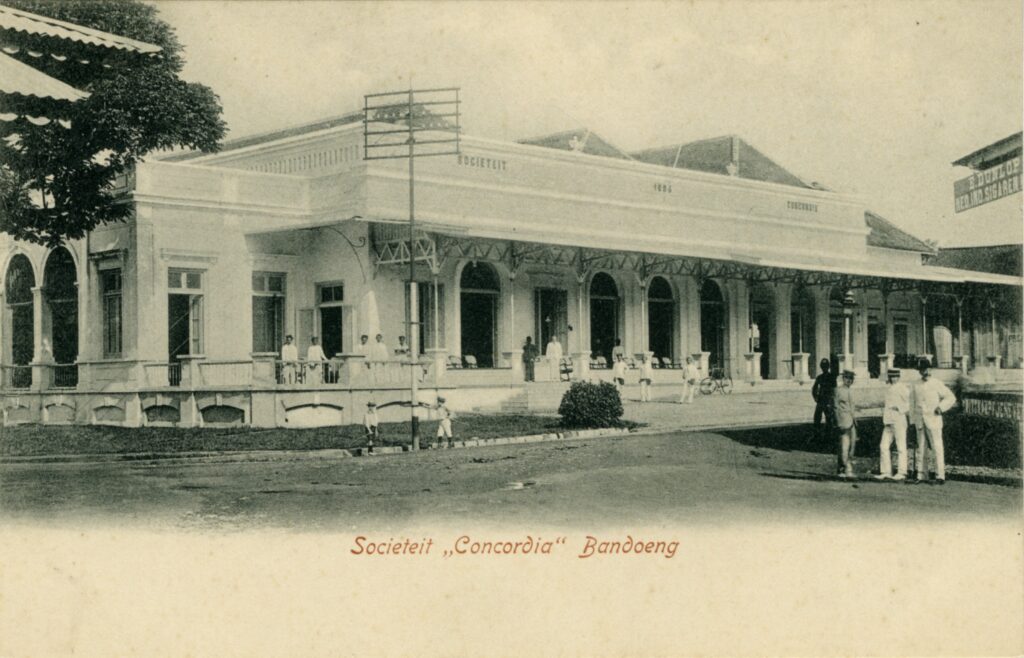

Bandung – April 21

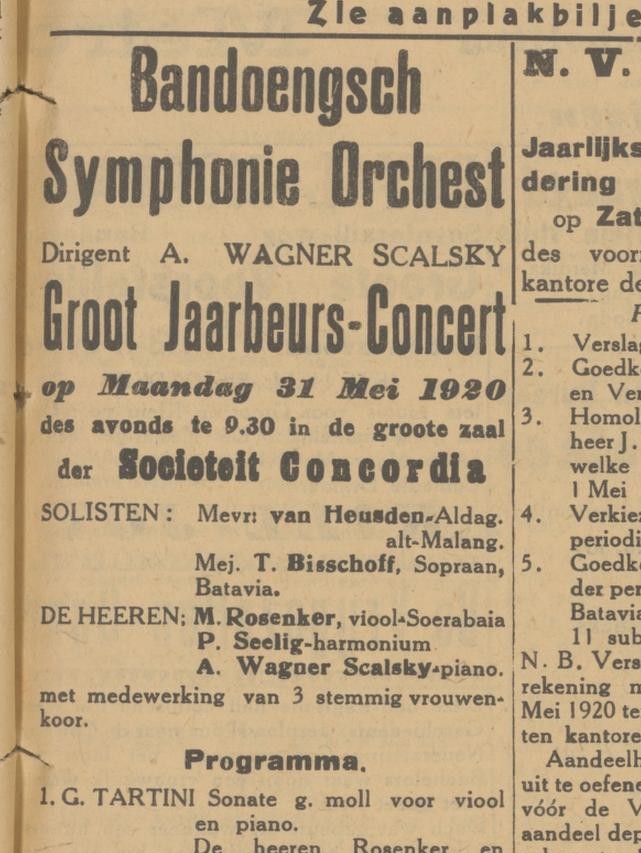

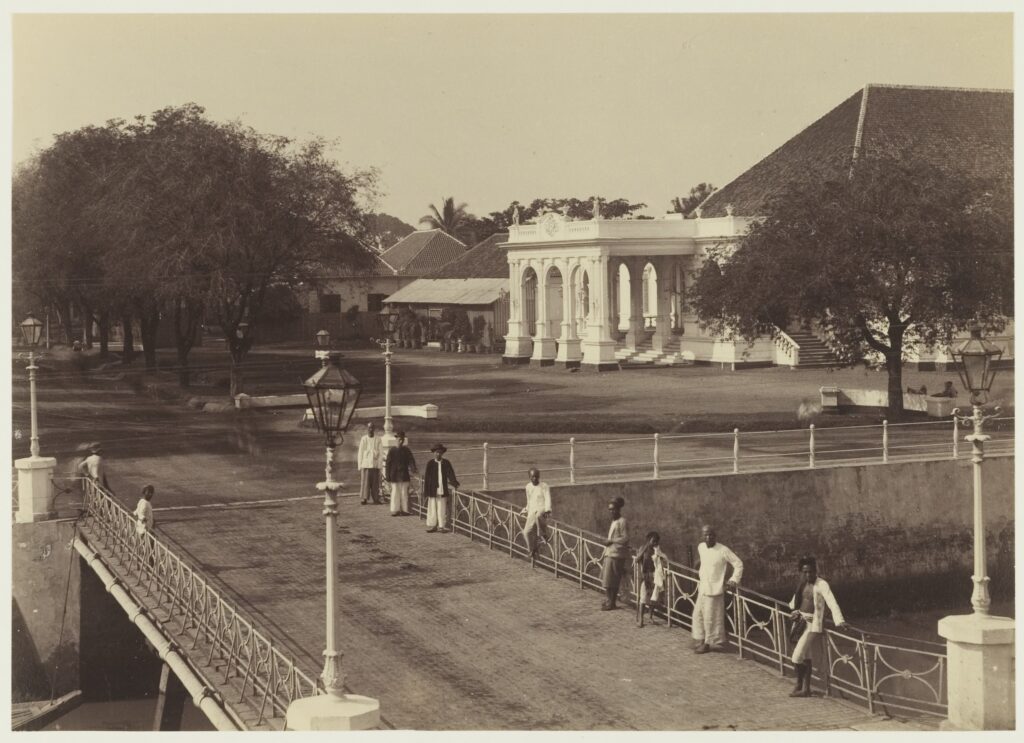

Their next show was at the Societeit Concordia building in Bandung, one of the biggest cities in Java with a large European and Chinese population. This concert venue, a whites-only club seen in the photo below, was demolished in 1926 and rebuilt with a new Art Deco design. After Indonesian independence, it was famously used as the venue for the 1955 Asia-Africa conference of nonaligned nations (the ‘Bandung Conference’).

Per a review in the local Preanger-Bode, it was as sparsely attended as their recent shows in smaller cities. The reviewer started by saying “Easter Monday was a bad day for the Zimro-Sextet to give a Chamber music evening in Bandung. There were only 40 people scattered in the large hall; Bandung was tired of going out.”[45] The writer objected to Russian repertoire like Glazunov intruding on the Mozart and Handel, but marveled:

Who in the Indies, where people live on general program music, has ever heard this five-piece? It is beyond the reach of our resources and artists from abroad do not bring along a clarinetist to bring out such vintage works by Mozart. If war and revolution had not driven the forces out of the old continent, we would not have remembered the existence of those artistic treasures, nor the pleasure they gave us long ago.[45]

Batavia – April 24-27

Zimro’s tour went from East to West across Java; eventually making their way to the capital Batavia. At that time it had around 250 thousand residents, much less than the 10 million or more it has today. It was a bustling and diverse city, with its own distinct minority culture (Betawi people). It was also the site of most government offices and the Governor General’s residence, although the administrative capital was technically in nearby Buitenzorg. As Zimro’s first concert date in the capital approached, someone called Ezerman wrote to the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad to praise the group and urge readers to attend.[46] I suspect this may have been J. L. J. F. Ezerman, a famous Sinologist.[47] Giving top marks for the concerts where he saw them play in other cities, he lamented that touring as a sextet was so much less profitable than touring as a duo in this market, and that “in smaller places people are not very receptive to this genre of art.”[48]

Unfortunately, the first Batavia show was not well attended either. The review the next day in Nieuws van den Dag accused dilettantes of ruining the music industry in Java, complaining that the seats were mostly empty despite the excellent musicianship. It noted that this kind of flop had happened several times lately when top-notch artists had arrived on the island.[49]

As in other cities, the reviewer was blown away by the interplay of the members of the quartet and their subtle interpretations. The reviewer from the Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad was more critical, judging the clarinet incongruous at some times and the choice of violin solo to be pandering to the audience.[50] Zimro’s second classical concert at the opera house in Batavia on April 27 was much better attended.[51]

Batavia – May 1

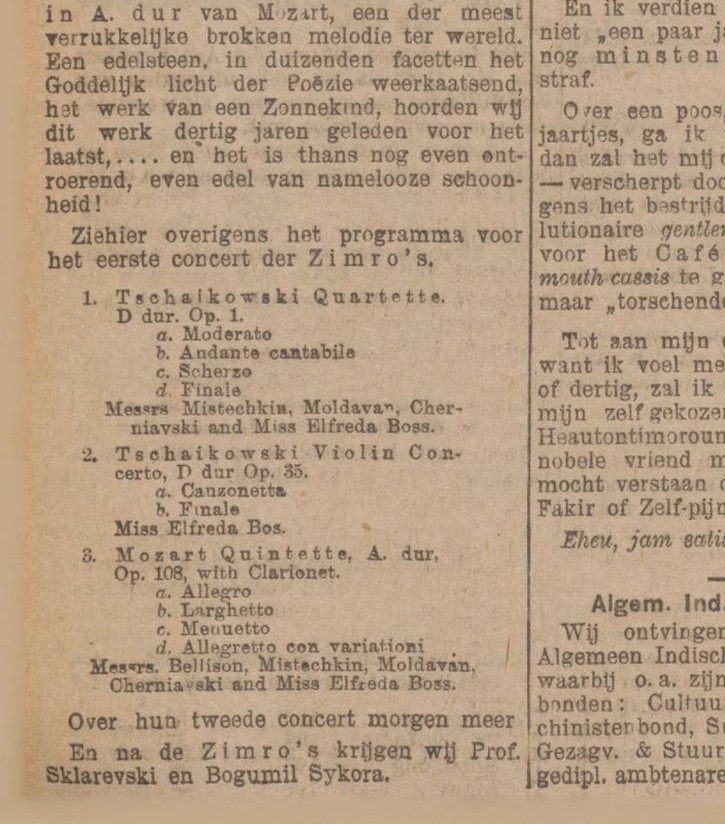

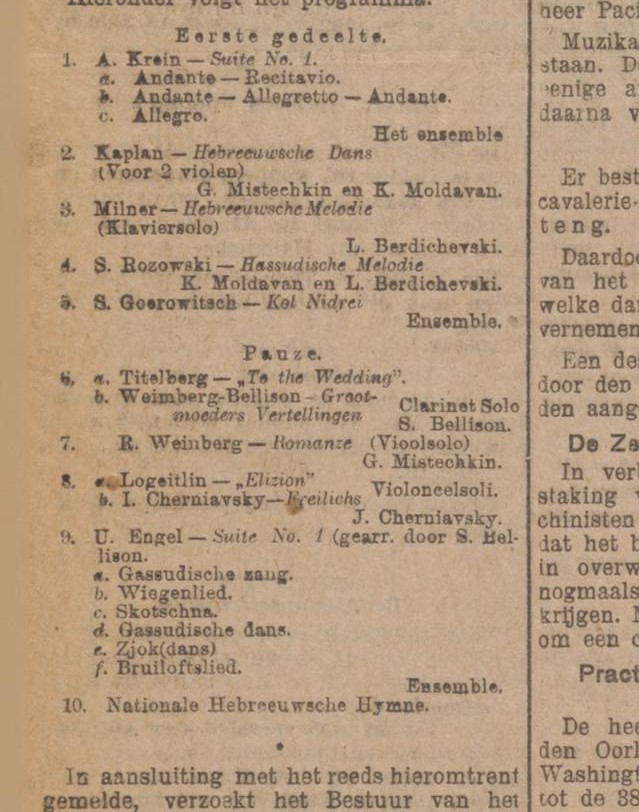

Zimro’s first public Jewish music concert in Java, as far as I can tell, was on May 1st in Batavia.[52] The concert programme was printed in the press, so we know that it consisted of Society for Jewish Folk Music compositions by figures like Krein, Engel and Rosowsky.

A reviewer “M.” in Nieuws van den dag (probably editor Jan Mulder) got very strange and lyrical about the event: “As the exiles sit by the streams of Babylon, so the Hebrew musicians sit by the stream of the modern world, and sigh and weep for what has been lost.”[53] He projected this melodrama onto the music:

It may be a group that, through Zionist action, wants to regain the land of the Fathers, but the Jewish spirit remains like one wandering the earth, and its endless longing […] could be heard in the music yesterday evening, laments […] more for what was, than for what has not yet come.

Since we know a lot of the music was modern arrangements of klezmer melodies, to me this seems a bit excessive, although I don’t doubt Zimro’s playing was very emotive. I interpret the flowery review as an example of Dutch Christian stereotypes about Jews. The end of this review also contains a rare mention of a non-European audience; as the event was opened up to government clerks and students who would would otherwise not be able to afford it, the reviewer mentioned an ex-MULO student with poor Dutch and a native clerk in Javanese dress standing up to thank the artists.[53]

Another review of this concert eventually made its way by mail to the Sumatra Post in Medan, where it was printed on May 16th. That reviewer, writing under the pseudonym Scripsi, explained the background of the group, before launching into this interesting take on what makes this Jewish music different:

Work by Jewish composers, who in their own country and in their regions such as Moscow, Odessa, etc., felt Jewish national life more painfully than a man like, for example, Meyerbeer, who fared a lot easier. Also: a wide variety, because in addition to the religious melody there are higher art forms as well as the simple, the suite, the romance, the dance tune, the national song. Which the Jewish composers in and from Western Europe did not give us, because they, being assimilated and free in society, were little aware or unaware of the dispersion of the people and of exile, […] [54]

Although the review says they suspected many listeners would eventually get bored of this type of music, they found it rather exotic:

The melody is strange to those who are used to Western music. It is not easy to follow because it cannot be predicted. The progression of a motif is impossible to guess, it is always a surprise in the musical sense. […] This introduces peace and simplicity to the character of the Hebrew music, sometimes also a great degree of sobriety, childlike joy and exaltation, as David must have once shown […][55]

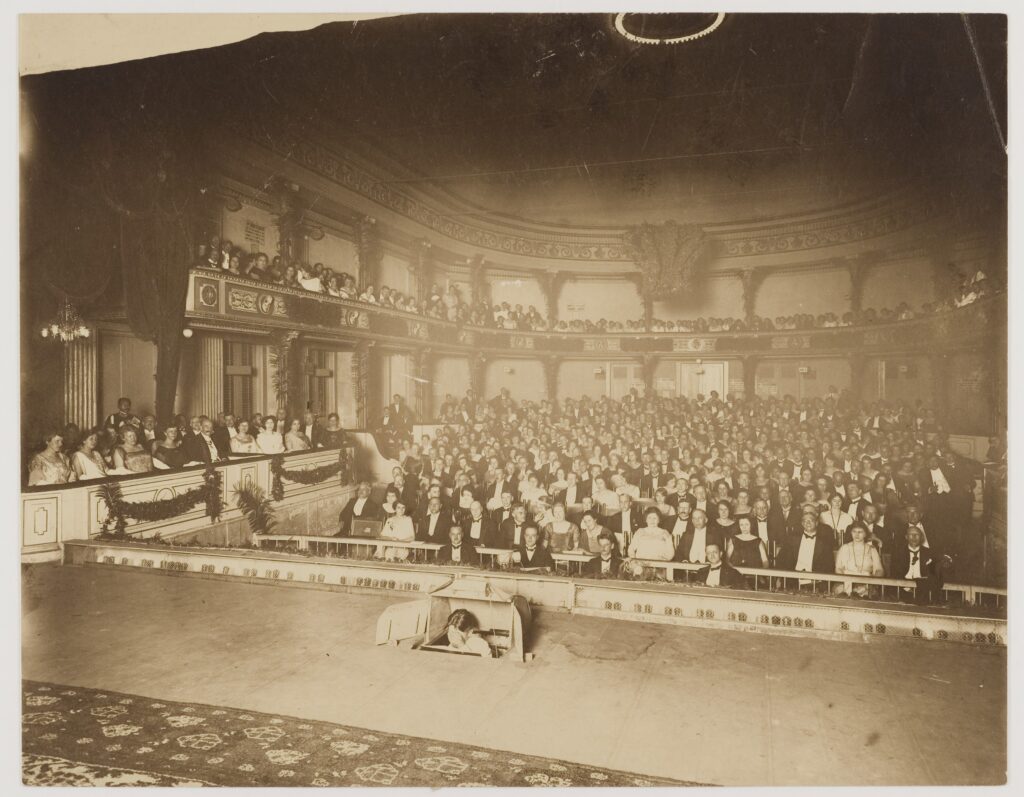

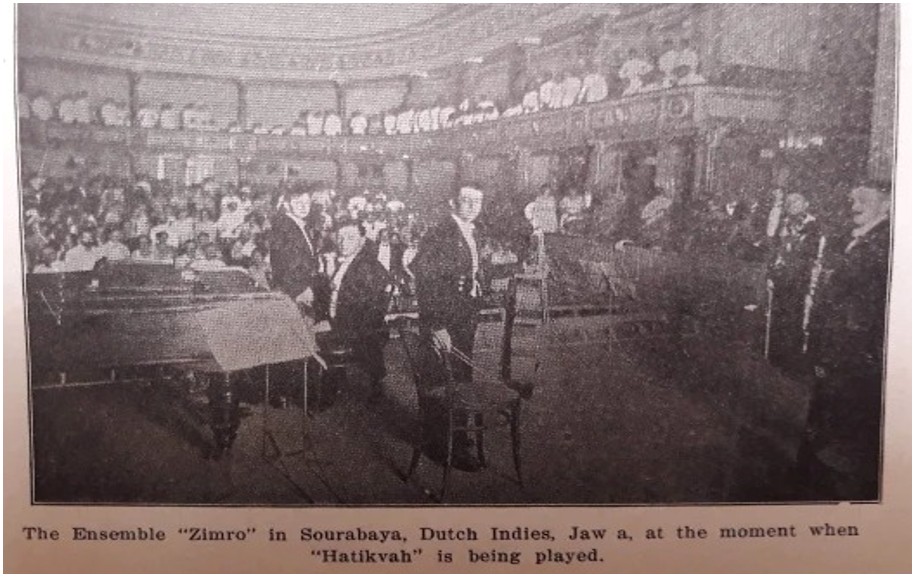

This undated photo, taken from behind the stage at a Zimro concert, was in their 1920 booklet. It’s the only photo I’ve seen so far of their tour in the Indies. Although the caption says it is in Surabaya, I suspect it is actually from the Jewish music concert at the Batavia Opera House. The balcony details look similar and Hatikvah was on their May 1 programme.

I wish the photo was clearer. In the photo we can see five of the members of Zimro, but not Elfrida Bos. In the audience, on the lower level, we can see what looks like mostly European men and women. What’s more interesting is that on the upper level it seems to be all Javanese or Arab men, who are all wearing the typical white jacket and black petji caps worn by modernist Muslim Indonesians. Between colonial newspaper reviews, Zimro’s booklet and anything else I could find, this is a rare documentation of non-Europeans having anything to do with their tour.

It’s a shame I couldn’t find more, but it makes me suspect that attendance may have been mixed at some of their other shows too. If I had to guess, I would say that the largest opera-house shows like the one photographed above likely had more mixed attendance, whereas smaller ones in whites-only social clubs likely did not.

The last thing I’ll mention is the caption, which must have been written with the American Zionist reader in mind. It says “The Ensemble ‘Zimro’ in Sourabaya, Dutch Indies, Jawa, at the moment when ‘Hatikvah’ is being played.” What significance would Hatikvah have held for a room full of Dutch socialites and aristocratic Indonesian Muslims? As far as I can tell from the newspaper reviews of this tour, not much.

Buitenzorg and Batavia – May 2-8

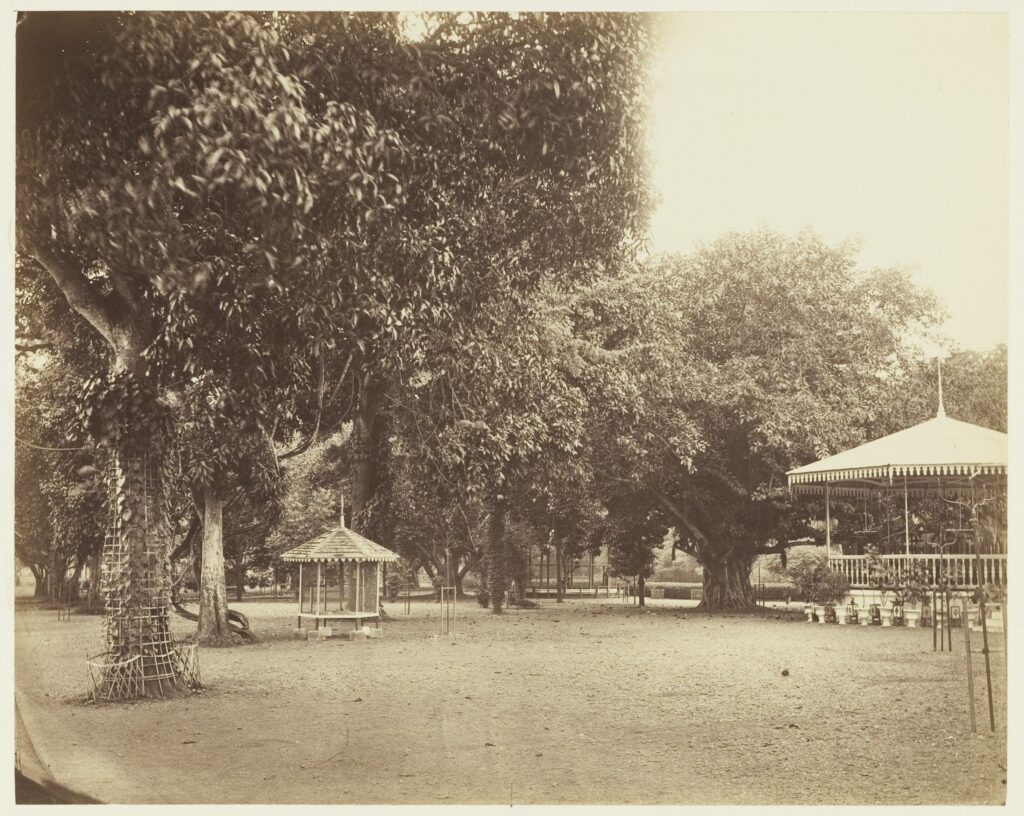

After that, Zimro stuck around Batavia for another week giving more classical music concerts. On May 2 they played a concert in nearby Buitenzorg (today Bogor in the Jakarta metropolitan area) attended by Governor General van Limburg Stirum’s wife, Lady Catharina Maria Rolina van Sminia.[56] Clearly Zimro had reached the peak of colonial society.

Zimro then played a few concerts at the Zoo and Gardens in Batavia. The first was on the evening of May 3rd.[57] The second was a morning concert at the same place on May 5th; it was tentatively postponed to the 8th when Elfrida Bos fell ill.[58] In the end, it went ahead on the 5th without her and with a rearrangement of the repertoire;[59] Mistechkin, Cherniavsky and Berdichevsky played Tchaikowsky trios for most of the concert, followed by assorted classical and Jewish pieces.[60]

On the 6th, de Preanger-Bode, printed an interesting editorial appeared which mentioned Zimro in the context of other Russian acts. It’s interesting so I’ll quote it at length:

Slavic Music. The artists who came during the war years remained “in the market” for a long time. The “Far East,” and Australia, and the link between them, our Indies, became their field of work. The good ones had nothing to complain about, they will have to admit that true art is highly appreciated there. The revolution in Russia has driven out several more. The result has been that the music world has become heavily dependent on the Russians, […] It is a busy musical life these days. One of the good consequences of this is that we we no longer have to stick to the stereotypical program music, there’s a blend to please everyone. There is already specialization. The Zimros in particular performed old chamber music and gave Batavia a specifically Hebrew evening.[61]

Elfrieda Bos recovered enough to play another concert for the Music and Theatre Association at the Batavia opera house on May 8th.[62]

It was also at this time that Zimro heard that they would be granted a visa to enter the United States, which had been approved in a May 2nd telegram from the Passport Office in the US to the American Consul in Shanghai;[63] a few days later, the news seems to have reached them in Batavia. The terms of the visa were for transit to Palestine, not settlement in the United States.

This was printed in multiple Indies papers via the ANETA wire service; the bulletin also noted that they would not be able to leave for two months and that they would continue their tour in Java.[64]

I mentioned that Indonesians are invisible in this coverage. But the experience of Zimro members are also barely present. The triumphalist descriptions given in their booklet printed in New York are hard to reconcile with the coverage in the colonial Dutch press. And I’m not aware of whether any of the members wrote memoirs that covered this period, even if most of them became famous musicians in America. The colonial press coverage often feels more like a performance of elite knowledge and competition between editorial personalities, rather than being deeply engaged with Zimro’s music.

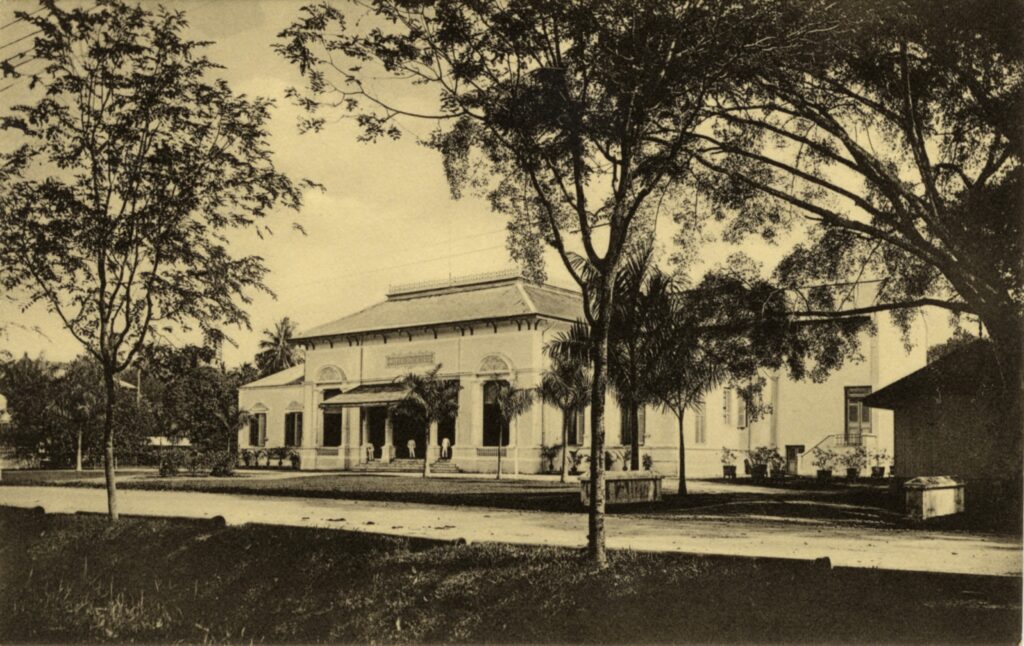

Semarang – May 9-10

Next Zimro headed east again to visit cities they had missed on their first tour from Surabaya to Batavia. On this second tour, around May 9 or 10 they headed to Semarang, the third of the major port cities in Java after Batavia and Surabaya, which is located on the north coast in Central Java. Also a diverse city with a large Chinese and European population, Semarang was rapidly industrializing and expanding during this time, and was the epicenter of the colony’s communist movement. It had been the base of Henk Sneevliet, considered the father of Indonesian communism and exiled from the colony a year earlier, and the headquarters of left-wing parties like the Indische Sociaal-Democratische Vereeniging (Indies Social Democratic Association) and the Sarekat Islam Merah (Red Islamic Union), both precursors to the Indonesian Communist Party which was founded in 1920.

On May 10th Zimro once again performed their special Hebrew music concert in Semarang. (I’m not sure if it was their first concert in town.) The liberal paper De Locomotief wrote a long article previewing their arrival a few days earlier, explaining how Zionism was gaining more and more sympathy worldwide due to the suffering of Russian Jews and explained to readers that they would get a rare glimpse of village music from Russia by its own practitioners.[65]. The paper even had a few Jewish editors in this era (most famously Jozef Emanuel Stokvis) which may explain the tone, although I’m not sure if they were directly writing this.

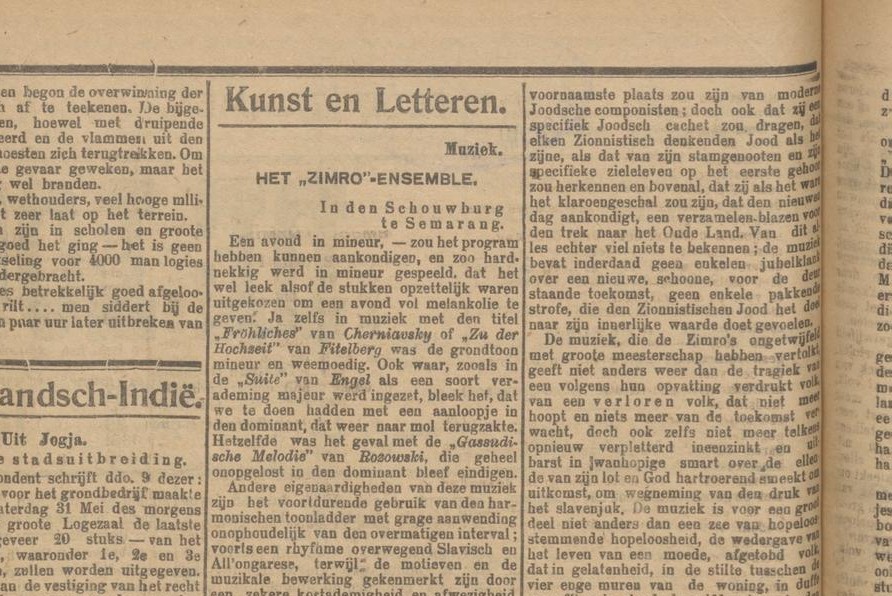

The concert was followed by a particularly interesting review by two anonymous critics from De Locomotief, which was refreshing after the purple prose seen in M.’s review on May 2nd. I think the first half is one of the most perceptive reviews I found of this tour. It begins:

“An evening in a minor key” could have been the evening’s title, played so loudly and stubbornly in a minor key that it seemed as if the pieces had been deliberately chosen to give an evening full of melancholy. Yes, even in music with the title “Fröhliches” by Cherniavsky or “Zu der Hochzeit” by Fitelberg, the key was more minor and melancholic.[66]

At first it seems like another complaint by someone unfamiliar with Jewish music. But the critic takes another angle:

What makes this Hebrew music anyways? It is also wrong to interpret the minor atmosphere that surrounds this music and which serves as an expression of subjects as being connected with something that can be referred to as Jewish martyrdom. Rather, the melancholy sound emanating from these works reflects the martyrdom of the Russian people, to which the composers belong. It is the suffering of this people, which is expressed in the music in harmonies specific to the people and the inescapable melancholy, which is certainly not a specific Hebrew sentiment, but Slavic – expressed here in tones is entirely in accordance with the social environment of old regime Russia.[67]

They go on to write that —yes, some old Hebrew melodies have been adapted here, but articulated and harmonized according to Slavic sensibilities, so that much or all of the original effect of the Jewish melodies are lost. He compares this to local Javanese music harmonized with Western chords; it still gives a very different effect from typical Western music, and if performed in a certain way can evoke a so-called Oriental feel, but isn’t itself a specimen of so-called Oriental music.

Another critic wrote the second half of the review and took a very different angle. They say that the music, while impressive, is not successful in its mission because the music is too morose to inspire a nationalist movement:

The musical rendition brings to mind an old, bent, broken man, in the last days of his long life, complaining about the loss of his former greatness and prestige, but not thinking one last time about regaining their greatness. Such a view is, I believe, not suitable for giving the Zionists confidence in their movement […][68]

Like M. from Batavia, I wonder if this critic is projecting a bit too much onto these arranged klezmer pieces. I would be curious to know the background and political views of this anonymous critic, even as I find it less insightful than the first review. It concludes:

While they are young, they bear the burden that has weighed on them for centuries and centuries and are the deeply-felt musical interpreters of it, making their musical performance a piece of tragedy that extends to an entire race. Indeed, the Zimros have managed to bring the desolate fate of the Jews of Eastern Europe into deeply poignant expression. And it is no coincidence that, if we have correctly observed, it was the Armenians, who could best sense the misery, were the first to rise from their seats when the performers played the Zionist national anthem as the closing song.[69]

May 11 – Jogjakarta

They continued south their tour in central Java to Jogjakarta, where they played in a small hall on May 11th.[70] Yogyakarta is a lot like nearby Surakarta, which Zimro had visited the month before; a city of classical Javanese culture ruled by a hereditary monarch. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a review of this show.

Around May 17th a strange claim was circulated in various papers in Java. De Preanger-Bode and Het nieuws van den dag reference a recent article in the Soerabaijasch Handelsblad complaining that the Indies government had recently surveilled members of Zimro, suspecting them of being Bolshevik infiltrators.[71] The red scare was in full force in Java as it was in America; colonial authorities were convinced that Soviet spies were already in league with Indonesian nationalists. De Preanger-Bode considered the surveillance of Zimro justified and said “better safe than sorry,” while Het nieuws van den dag ridiculed it as misguided, although they proposed plenty of other people to be investigated instead. Unfortunately, that era of Soerabaijasch Handelsblad isn’t digitized in the usual places so I can’t read the original article. The colonial secret police kept meticulous records, so the facts of the surveillance are probably sitting in an archive in the Netherlands.

Batavia – May 17-25

Zimro returned to Batavia to play another series of concerts. The earliest I could find was at the Batavia Zoo and Garden again on May 17.[72]

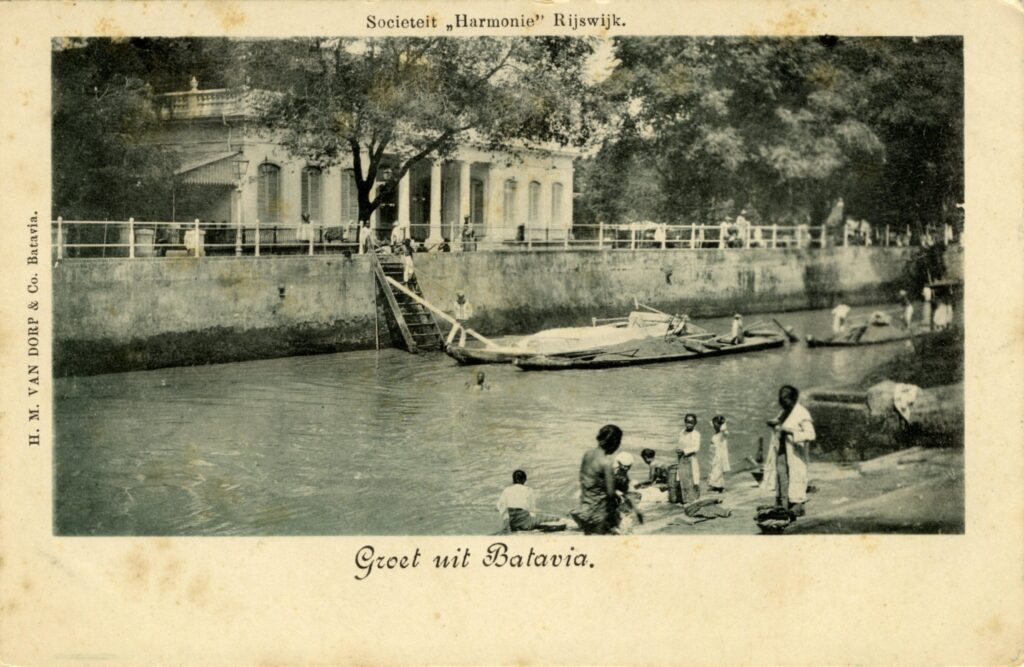

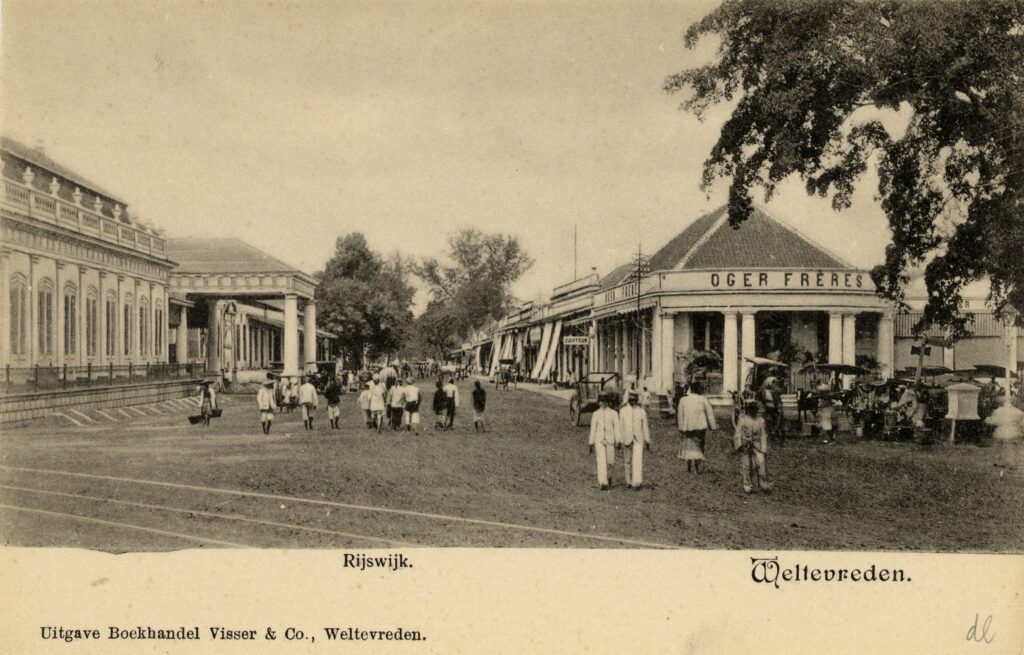

They played on May 22nd at the Societeit Harmonie in Weltevreden (today Sawah Besar in metropolitan Jakarta), which may have been the most elite space Zimro entered during their trip. Designed during the period of Napoleonic rule in Java, the Societeit Harmonie was the oldest and most famous European social club in Java, used for decades as the venue to accept foreign dignitaries.[73] Unfortuntely, I couldn’t find a review so I don’t know more than that.

Discussion in the papers also continued about the secret police surveillance of Zimro. De Preanger-bode once again justified it as necessary and wise:

Lately we discussed the caution of the Indies government, which controls the movement of the Russians pouring in here, and we wrote that we, in contrast with the disapproval of the Soerabaiasch Handelsblad, also considered surveillance of the members of the Zimro-sextet to be fully justified. We believe that the musicians mentioned here bring nothing other than their art. However, the board must take into account the fact that revolutionary agents prefer not to travel without a mask. They are also not used to stating their true nature on their cards: “Mr….ovsky; Bolshevist”. Control over all Russians stranded here is therefore necessary. One can only demand that this supervision be as inconvenient as possible. In the meantime, in connection with the above, we learned that several Russians have already been arrested in the ports because something was not right.[74]

The Fox News of its era!

By late May, Zimro was getting ready to leave Java and played several “farewell” concerts. The first of these was on June 25th with singer Maria Elizabeth Russer, wife of Petrus Sitsen, a well-known construction contractor and patron of the Batavia kunstkring.[75]

At around the same time, papers in Semarang covered a different kind of effort involving Zimro. It related to a volcanic mudflow from Mt. Kelud in East Java on May 19th, a disaster which had killed over 5,000 people and displaced many others. The colonial Resident,[76] the mayor of Semarang, and a committee representing the various ethnic groups in the city, were calling for Zimro to return and play a charity concert to help victims of the disaster.[77] It was eventually scheduled for June 4th at the city opera house.[78] It was also billed as a farewell concert from Semarang.[79]

Surabaya – June 2

As part of their farewell tour they played in Surabaya again on June 2nd.[80] I couldn’t find much about it.

Semarang – June 3

Their June 3 concert in Semarang was one of the two from this tour mentioned in the 1920 booklet. It was another of their Hebrew music evenings and one of the few fundraising for their supposed cause. In it, the treasurer of the Netherland India Zionist Union S.S. Rappoport called it a “tremendous moral and financial success” and tallied the income at 3600 guilden.[81] I couldn’t find coverage of it in the Dutch papers, so maybe it was a private concert limited to donors.

Semarang – June 4

The next day, the June 4 benefit concert at the opera house in Semarang had a mixed repertoire, with a first act of Western European classical music, and a second act of Russian empire music; Zimro closed with Alexander Spendiaryan’s Crimean Sketches (1903), based on Crimean Tatar themes.[82] De Locomotief’s critic found it an excellent concert, noting “The Kol Nidrei by Bruch, a cello solo by Mr Cherniavski, was one of the most beautiful songs of the evening, in which the cello sung in a deep and moving voice. Finally, a strange ensemble number by Spandiarow, wild and restless, with song and dance motifs from a world that is far away from us.”[83] In the end the concert raised 1800 guilden for the mudslide victims.[84]

Weltevreden (Batavia) – June 6

Zimro returned to Batavia to play one last show on June 6th in Weltevreden.[85] I couldn’t find much about it, but I think it was the last show they played on their two month tour of Java.

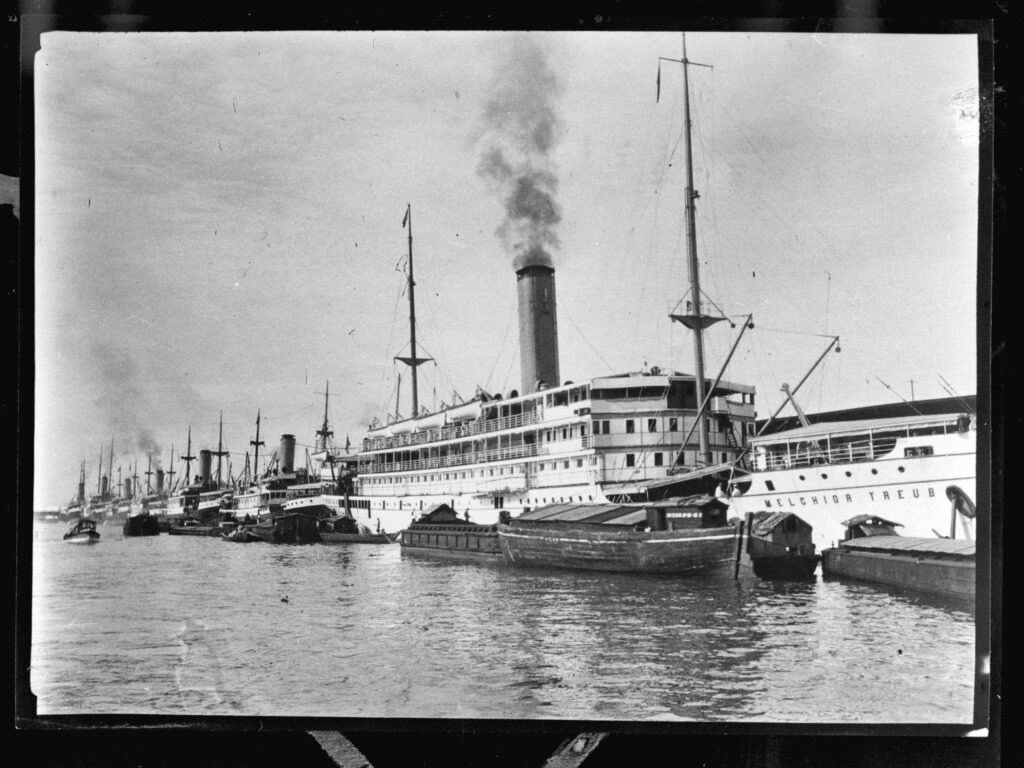

The Dutch press in Sumatra, observing the tour in Java at a distance, had occasionally printed commentary and wire reports about it. On May 22nd the Sumatra Post confirmed that plans were finally being worked out for a local tour. The kunstkring in Medan had agreed on a guarantee for a Zimro concert there,[86] with the Deli Courant reporting that they would be performing around June 10th.[87] They sailed aboard the S.S. Melchior Treub from Batavia to the east coast of Sumatra, not far from Singapore and the Malaysian peninsula, and went inland to Medan on the 10th.

Medan – June 11

Zimro’s only concert in Sumatra was the one in Medan on June 11th at an exclusive club called the Witte Sociëteit (or white society). A bit on the nose!

Medan, the biggest city in Sumatra, was a pretty rough boom town with tobacco plantations and other extractive industries, and was seat of the Deli Sultanate. This mundane notice published in that day’s paper gives a feeling of the setting: “We are requested to politely appeal to the goodwill of the car-owning public, namely not to drive cars into the club grounds after a quarter past nine (the start time); and above all, to refrain, as much as possible, from honking.” The concert did not include their Jewish material and consisted of Mozart, Tchaikowsky and other classical pieces.

Deli Courant reviewed the concert the next day; they found Zimro to be technically impressive, saying that Elfrida Bos rose to the task when faced with difficult solos, although they were ambivalent about the Tchaikowsky pieces.[88] They noted that the heat in the venue seemed to be causing tuning problems which the group did their best to cope with. The Sumatra Post also reviewed their concert, lamenting that such an excellent chamber ensemble was leaving so soon and would almost certainly never come back.[89] They also commented on the heat in the room. While they were less impressed with Elfrida Bos, they found Mistechkin to be a masterful musician who left his colleagues very little space to do anything on their own. For some reason the Post also published another piece ridiculing the editor of the Deli Courant for disliking Tchaikowsky and saying she was “tired of life.”[90]

By the night of this concert it was already known that Zimro would not be able to appear at the rest of its planned Sumatran dates: June 12th in Tebing-Tinggi, June 14 in Simalungun (at Pematangsiantar), and June 15 in Tanjung Balai–all three are fairly backwater towns southeast of Medan in the region between Lake Toba and the Straight of Malacca. They also abandoned the notion of playing in Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, and other places on the way back to Shanghai, which they now wanted to depart for immediately to make a planned sailing to North America. They had offered to return their advances for the other concerts, but were rebuffed.[91]

Aboard S.S. Melchior Treub – June

Zimro returned to the coast to catch the S.S. Melchior Treub to Singapore; while aboard it they played a charity concert once again for disaster victims, this time for the Smeroefonds,[92] which had been founded in 1911 to repair the damage of another eruption in East Java in 1909, but which now acted as a general disaster relief fund.[93]

From there they took another passage to Shanghai, where they may have spent two or three weeks. An article mentioned their farewell concert in Shanghai on July 10th.[94]

Zimro sailed from Yokohama to Victoria, B.C. on the Empress of Russia, arriving on July 28th. From there they went across Canada, probably by train, to Montreal and then to New York, entering the US on August 3rd.

During the two years after their arrival in the United States, Zimro were celebrated by elite art music and Zionist circles. The group seems to have been as much of a novetly in the US as in the Indies; they may have been the first ensemble to play Russian Jewish art music at that level.[95] During this time Prokofiev composed his Overture on Hebrew Themes (1919) for the group’s Carnegie Hall debut.

It was during this time that Zimro published the bilingual booklet that I mentioned earlier. But Zimro disbanded in 1921, apparently when Bellison was invited to join the New York Philharmonic as first clarinetist.[96] None of them went to Palestine despite it being the pretext for their admission to the US. The other members also settled in the US and joined various classical, theatre or radio orchestras. Neil Levin believes that they had intended in good faith to continue to Palestine but that they had “succumbed individually to the musical as well as practical temptations offered by America—and especially by New York.”[97] I do wonder if ‘good faith’ is a meaningful description.

A series of exchanges in the Hebrew Standard in late 1921 give us a rare glimpse into the end of Zimro. In September, in his Personalities column, the writer J.K. reminisced about the dramatic arrival and promise of the group in New York two years earlier. He mentioned spotting Cherniavsky playing in a Jewish theatre in New York and remarked on “the rather sorrowful fact is that the Zimro Ensemble should have been forced to wander from its path. And yet there was really no other result possible for their enterprise.”[98]

A few weeks later, Cherniavsky replied in a letter to the editor. He denied that he had been leading a quartet in a theatre and said:

As to the Zimro, although I heartily agree it is a “sorrowful fact” that the Zimro was unable to continue on its way, it was not at all due to the inability of Jewish music to hold “American music lovers,” but to the truly deplorable circumstance that there is not one rich Jew who cared to become patron to the ensemble.[99]

He continued:

The ideal to build an art temple in Palestine, that brought us together and that took us over the world for three years, burns as strongly in my heart. We were forced to stop. But as soon as I see the way clear, and if there is only an answer to my call, the work will be resumed—and let us hope to a successful end.[100]

But Bellison and Cherniavsky never reconstituted the group.

I’ll conclude with a few of my own thoughts of my own on this tour.

First, Zimro’s passing embrace of Zionism and its use to emigrate from the early Soviet Union to the United States. Although in-depth studies do address it,[2] promotional materials for Zimro tribute concerts and albums tend to gloss over this aspect. For example, a YIVO Facebook post from a centenary celebration concert in 2019 says:

a special centenary concert celebrating the Zimro Ensemble’s historic global tour in 1919. The Zimro was a sextet of virtuoso musicians who championed early Jewish-themed classical music. Theirs is the story of the immigrant experience and international musical ambassadorship in the early 20th century. […] This program will coincide with the anniversary of Zimro’s sold-out Carnegie concert that concluded their tour through Siberia, the Far East, and America

Another tribute group from the UK, the Zimro Trio, frames it as such on their website:

In 1917 a group of Russian Jewish musicians set out from St Petersburg on an intrepid journey lasting two long years. They were called Zimro. A group of six classical musicians (string quartet, clarinet and piano), Zimro was formed by one of the foremost clarinettists in Russia, Simeon Bellison. They toured Jewish communities throughout Eastern Europe and the Far East, visiting the far flung corners of Russia, Siberia, China, Japan, Indonesia and Alaska before finally arriving in America in 1919, where they met up with their close friend and colleague, the composer Serge Prokofiev.

It’s one way to look at it, and indeed they were in a sense ambassadors to modern Russian/Jewish art music in places that had little exposure to it. But I wouldn’t say they seem like ambassadors by choice. They were ready to exit China immediately if they could in late 1918.

Back to their ‘mission’. To me it’s made worse in the context of fundraising for it in racially segregated colonies. Bellison continued to make Zionist art a part of his artistic vision later on, so maybe he was the biggest believer among them. The Society for Jewish Folk Music basically ended at around the time they were leaving in 1918, with its key members dispersing around the world. In that way Zimro weren’t exactly carrying on the mission they were charged with, although they became like mascots for various regional Zionist organizations instead. Beyond that it’s hard to characterize their actual relationship to the ‘mission’ or what interactions they had about it along the course of their three years of traveling. Almost everything in print feels tailored to the propaganda of their cause, which in the end they abandoned.

Second, the reception of Zimro by the public in Java and Sumatra. Today, this tour simply wouldn’t take place at all, due to the hostility of Indonesians to Zionism. But in their time it doesn’t seem that many people in the Indies even understood the significance of Zimro’s mission or ideology. I would say, in most cases newspaper writers did not pay attention to the Jewish nature of the ensemble and saw them primarily as yet another group of Russian emigrés. In the reviews of their Hebrew Evening concerts, there was recognition of the significance of their ideology in relation to music and Russian Jewish history. But then, with a few exceptions the tone tends to be pitying sympathy but also the condescension and stereotyping of Western European Christians.

As for the opinions of any Indonesians who saw the concerts or had to work to support this tour, we also know essentially nothing. Elite Indonesian Muslims of the kind who may have been in their opera house concerts often spoke Arabic and studied in Cairo or Mecca, and were very aware of international politics. Even working class Indonesians, who may not have been literate and who may have never left their local district, were influenced by anti-colonial movements and religious movements and had plenty of opinions. It’s hard to know.

Third, the money from their mission. We know from many examples in our North American history that many utopian schemes from that era either collapsed or had unintended bad consequences. In that sense it’s far from unique. I don’t know enough about historical currencies and charities to understand exactly how much money they raised in different countries (Rubles, Gulden, US Dollars) or where that money ended up since the Temple of Art project never happened. All the printed materials made a big deal about the fact that it was being put aside by local organizations, not collected by Zimro, so I doubt they pocketed it. That would be a different, and honestly funnier story. Maybe it went into the general revenues of the Jewish National Fund or some other project. On balance, a bad scheme in my opinion: a smoke-and-mirrors campaign which took money out of places that could probably have used it.

Fourth, I made a lot of use of photographs of Java from the KITLV collection, which is a huge digital collection from the Netherlands focusing on Indonesia and the Caribbean. I find these photos fascinating, but I sometimes also think they are a lie. The thousands of photos of orderly tree-lined streets and art deco buildings, or Europeans posing sternly with Indonesian servants, does not really represent the social change, pain and dynamism of that era. There are other photos in there which do show Indonesian daily life, but often in stereotyped or posed scenes. The ability to show the exact buildings and streets someone visited in 1919 is tempting, but sometimes I feel like it is conveys a highly misleading view of the past.

Fifth: on being European in the Indies, and how little it mattered that someone was Russian or Jewish. Zimro probably didn’t want to be in Java too much in the first place, but that was true of many Europeans working there in that era. It’s how the Indies system worked in that time, which is very different from our conception of settler colonies where Europeans arrived and took on a new identity as citizens of the colony. The Indies imported thousands of Europeans on a temporary basis in the interests of keeping a system going where under 0.5% of the population ran everything and extracted massive amounts of wealth. And when those people left having made some money, they invariably carried the experiences and attitudes with them, for better or worse. I couldn’t find any trace of what impression this left on the Zimro members. Although the fact that Joseph Cherniavsky briefly went to work in South Africa in 1949 feels a bit connected to me.

Finally, the concept of a group of artists working under a very specific personal narrative, only focused on that and passing through wealthy and exclusive spaces insulated from the many problems of the world, in an era of almost unimaginable suffering and cruelty. Putting aside all the things I do appreciate about Zimro, such as their musicianship and dedication to Yiddish art music. It still leaves a bad taste in my mouth, and makes me think about how we shouldn’t be as musicians and cultural workers a century later.

[1]. James Benjamin Loeffler, The most musical nation: Jews and culture in the late Russian empire (Yale University Press, 2010) p.183-190.

[2]. Neil W. Levin, “The Russians Are Coming!—The Russians Have Stayed! A Little Known Episode in the History of the New Jewish National Music School: The Tour of the Palestine Chamber Music Ensemble ‘Zimro'”. In Jüdische Kunstmusik im 20. Jahrhundert: Quellenlge, Entsehungsgeschichte, Stilanalysen, edited by Jascha Nemtsov, 73–90. Jüdische Musik 3. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 73. Charles P. Schmidt, “Bellison, Simeon,” in Grove Music Online, Accessed May 19 2024.

[3]. The Palestine Chamber-Music-Ensemble ‘ZIMRO’: Its aims and activities = Palestina Kamer-Muzik Ansambl Zimrah: Tetigkeyt un Oyfgaben (Pinski-Massel Press, New York, n.d.).

[4]. The Palestine Chamber-Music-Ensemble ‘ZIMRO’, p. 1. The Yiddish version phrases it slightly differently; propagandiren (propagandize) instead of propagate Jewish art music; the Temple of Art is a kunst-tempel,and

[5]. The Palestine Chamber-Music-Ensemble ‘ZIMRO’ p.3.

[6]. Loeffler, The Most Musical Nation, p.373.

[7]. Anne Mischakoff Heiles, America’s Concertmasters (Sterling Heights, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 2007), p. 286-7.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Frédérique Petrides, “Women in Music,” October 1938, as reproduced in Jan Bell Groh, Evening the score: Women in music and the legacy of Frédérique Petrides (Fayetteville : University of Arkansas Press

[10]. The Palestine Chamber-Music-Ensemble ‘ZIMRO’ p.9-10.

[11]. Charles K. Moser, letter to the Secretary of State (unpublished letter, Harbin, 1918). From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[12]. Kees van Dijk, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War, 1914-1918 (Leiden: Brill, 2007) p.547. See also Ravando Lie, “Learning (or failing to learn) from the lessons of the 1918 Spanish Flu.”

[13]. van Dijk, The Netherland Indies and the Great War, p.593.

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. Edward Newman, letter to Division of Passport Control (unpublished letter, New York City, 1919). From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[16]. Edward Newman, letter to Division of Passport Control (unpublished letter, New York City, 1919). From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[17]. Phillips, letter to American Consulate in Harbin (unpublished letter, Washington D.C., 1919). From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[18]. “Het Zimro-sextet,” De nieuwe vorstenlanden, Surakarta, April 7 1919, p. 2.

[19]. “Het Zimro sextett,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad Batavia, April 19 1919, p. 1.

[20]. “Mario Paci: An Italian Maestro in China.” Accessed on May 21 2024.

[21]. “Mario Paci, Shanghai, letter to Sara Paci, Java, 1919 January 21-25,” accessed on May 21 2024.

[22]. van Dijk, Kees, The Netherlands Indies and the Great War: 1914-1918 (KITLV Press, Leiden, 2007) p.579.

[23]. Susan Abeyasekere, Jakarta: A History (Oxford University Press, Singapore, 1987), p.100.

[24]. Van Dijk, Netherland Indies and the Great War, p.23-4.

[25]. R. Franki S. Notosudirdjo, “Musical Modernism in the Twentieth Century” in Recollecting Resonances (Brill, 2014), p. 129.

[26]. Van Dijk, Netherland Indies and the Great War, p.24.

[27]. Purnawan Basundoro, “The Two alun-alun of Malang (1930–1960),” in Freek Colombijn and Joost Coté, eds., Cars, Conduits, and Kampongs: The Modernization of the Indonesian City, 1920-1960 (Brill, Boston, 2015), 280-2.

[28]. R. Franki S. Notosudirdjo, “Musical Modernism in the Twentieth Century” in Recollecting Resonances (Brill, 2014), p. 139-40.

[29]. Frances Gouda, Dutch Culture Overseas: Colonial Practice in the Netherlands Indies, 1900-1942 (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2008) p.158.

[30]. Amir Pasaribu, Analisis Musik Indonesia (PS, 1986), p. 82. Also discussed in R. Franki S. Notosudirdjo, “Musical Modernism in the Twentieth Century” in Recollecting Resonances (Brill, 2014), p. 140.

[31]. Many examples from 1919 are given in this article: “Delische Brieven. Medan, 24—9—’19 Russiana.” De locomotief, Samarang, October 4 1919.

[32]. Hamonic Gilbert, “Note sur la communauté juive de Surabaya,” in Archipel, volume 36, 1988. Villes d’Insulinde (I) pp. 183-186; Jonathan Goldstein, Jewish Identities in East and Southeast Asia (De Gruyter: Oldenbourg, 2015), 184.

[33]. Hamonic Gilbert, “Note sur la communauté juive de Surabaya,” in Archipel, volume 36, 1988. Villes d’Insulinde (I) pp. 183-186

[34]. Jonathan Goldstein, Jewish Identities in East and Southeast Asia, 184. See also Leonard Chrysostomos Epafras and Rotem Kowner, “From a Colonial Settlement to a New Identity: The Rise, Fall and Reemergence of the Jewish Community in Indonesia,” in Jewish Communities in Modern Asia: Their Rise, Demise and Resurgence (Cambridge University Press, 2023), p.163-85.

[35]. Hamonic Gilbert, “Note sur la communauté juive de Surabaya,” in Archipel, volume 36, 1988. Villes d’Insulinde (I) pp. 183-186.

[36]. Jonathan Goldstein, Jewish Identities in East and Southeast Asia, p.177.

[37]. Chrysostomos Epafras and Rotem Kowner, “From a Colonial Settlement to a New Identity,” p.168-169.

[38]. “Een nieuw Sextet,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad Batavia, March 12 1919, p. 1.

[39]. ibid.

[40]. “SOERABAJA, 29 Maart 1919. Het Zimro-ensemble,” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, March 31 1919, p. 5.

[41]. “Het Zimro-sextet,” De nieuwe vorstenlanden, Soerakarta, April 7 1919, p. 2.

[42]. “Uit Solo,” De locomotief, Semarang, April 16 1919.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. “Telegrammen,” De Preanger-bode. Bandung, April 22 1919.

[45]. “Kamermuziek,” De Preanger-bode, Bandung, April 22 1919.

[46]. “Het Zimro sextett,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad Batavia, April 19 1919, p. 1.

[47]. “Comptes rendu,” in Archipel, no. 101, 2021, p. 265.

[48]. “Het Zimro sextett,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad, April 19 1919.

[49]. “Concert-avond. Het Zimro-ensemble, Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, April 25 1919, p. 1.

[50]. “Concert Zimro Ensemble,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad, Batavia, April 25 1919, p. 1.

[51]. “De Zimro’s,” De locomotief, Semarang, April 28 1919.

[52]. “Hebreeuwsche Muziekavond,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad, Batavia, April 30 1919, p. 2.

[53]. “Hebreeuwsche muziek-avond,” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 2 1919, p. 1.

[54]. “Uit Batavia,” De Sumatra post, Medan, May 16 1919, p. 1.

[55]. Ibid.

[56]. “Buitenzorg, 3 Mei (Aneta.) Het Zimro-ensemble.” De locomotief, Samarang, May 3 1919.

[57]. Advertentie. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 3 1919, p. 7.

[58]. “Uitgesteld concert,” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 5 1919, p. 2.

[59]. “Zimro-sextet te Buitenzorg,” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad Batavia, May 5 1919, p. 2.

[60]. Advertisement. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië. Batavia, May 2 1919, p. 4.

[61]. “Slavische muziek,” De Preanger-bode, Bandung, May 6 1919.

[62]. “Zimro Concert.” Bataviaasch nieuwsblad, Batavia, May 7 1919, p. 2.

[63]. Philips, letter to American Consul General in Shanghai (unpublished, May 2 1919). From the collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

[64]. “Weltevreden, 8 Mei (Aneta). Het Zimro-ensemble.” De locomotief, Samarang, May 8 1919.

[65]. “Stadsnieuws, Semarang 7 Mei. Het Zimrosextet,” De Locomotief, Semarang, May 7 1919.

[66]. “Kunst en Letteren. Muziek. HET „ZIMRO”-ENSEMBLE. In den Schouwburg te Semarang.” De locomotief, Samarang, May 12 1919.

[67]. “Kunst en Letteren. Muziek. HET „ZIMRO”-ENSEMBLE. In den Schouwburg te Semarang.” De locomotief, Samarang, May 12 1919.

[68]. Ibid.

[69]. Ibid.

[70]. “Zimro.. ” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 12 1919, p. 3.

[71]. “VAN DEN DAG.” De Preanger-bode, Bandoeng, May 17 1919. “Op de bolsjevisten-jacht.” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 17 1919, p. 1.

[72]. “Planten- en Dierentuin.” Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, Batavia, May 17 1919, p. 2.

[73]. Susan Abeyasekere, Jakarta: A History (Oxford University Press, Singapore, 1987), p.54-5.

[74]. “Voorzichtigheid,” De Preanger-bode, Bandung, May 22 1919.

[75]. Zimro concert.. Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, Batavia, 26-05-1919, p. 2.

[76]. “Hulpverschaffing.” Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, May 28 1919, p. 6.

[77]. Stadsnieuws. Voor de slachtoffers van de Kloet.” De Locomotief, Semarang, May 27 1919.

Nederlandsch-Indie. Een sinister record.” De Preanger-bode“. Bandoeng, May 28 1919.

[78]. Stadsnieuws. Het Zimroconcert.. De Locomotief, Semarang, May 28 1919.

[79]. Afscheidsconcert der Zimro’s. Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, June 2 1919, p. 2.

[80]. Soerabaja, 2 Juni (Partic. *). Het Zimro-ensemble.. De Locomotief, Semarang, June 3 1919.

[81]. The Palestine Chamber-Music-Ensemble ‘ZIMRO’, p. 28.

[82]. Kunst en Letteren. Het Zimro-Concert.. De Locomotief, Semarang, 04-06-1919. Geraadpleegd op Delpher op 02-06-2024,

[83]. “Stadsnieuws. Het Zimro-Concert voor de Kloetslachtoffers,” De Locomotief, Semarang, June 5 1919.

[84]. Stadsnieuws. Zimro en de Kloadslachtoffers, 10 JUNI.” De Locomotief, Semarang, June 10 1919.

[85]. “De Zimro’s.” Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, Batavia, June 7 1919, p. 2.

[86]. “Het Zimre-sextet.” De Sumatra post”. Medan, May 22 1919, p. 11.

[87]. “Als Duitschland weigert?.” Deli courant, Medan, May 26 1919, p. 1.

[88]. “Het Zimro-concert,” Deli courant, Medan, June 12- 1919, p. 1.

[89]. KUNST. Het Zimro-ensemble.. De Sumatra post, Medan, June 12 1919, p. 10.

[90]. „Wer nicht die Sehnsucht keant” De Sumatra post, Medan, June 13 1919, p. 5.

[91]. “Het Zimro-concert,” Deli Courant, June 12 1919.

[92]. Liefdadigheids-concert aan boord s.s. „Melchior Treub”.Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, June 16 1919, p. 2.

[93]. “Java, 1919: Colonial Disaster Relief,” accessed on June 2 2024.

[94]. “’Zimro’ Sextette: The farewell concert,” The Shanghai Times, July 12, 1919 Accessed in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[95]. Levin, “The Russians are Coming,” p.83-88.

[96]. James Loeffler, The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire (Yale University Press, 2010), p.241.

[97]. Neil W. Levin, “The Russians Are Coming!” p.84.

[98]. J.K., “Personalities,” in The Hebrew Standard, September 9 1921.

[99]. Joseph Cherniavsky, letter to the editor, in the Hebrew Standard, September 30, 1921.

[100]. Ibid.