My first post on here two years ago was about where to find old klezmer music in the U.S. Library of Congress collection. Back when I was trying to get a handle on what is out there, I came across a lot of references to 1920s Ukrainian music which was copyrighted by immigrant Jewish musicians in New York City. I was curious, but I didn’t order many of them, wanting to focus on more “Jewish” music first and Romanian music second. But now, I want to explain the process of how those kinds of scores (and later scores by immigrant Ukrainian musicians) can be obtained even if, like me, you aren’t located in the U.S. and can’t afford a plane trip to Washington D.C.

What scores?

Prior to the 20th century, music publishers and composers in the U.S. submitted scores to the Library of Congress to secure their ownership over music they had composed or arranged, often for the purpose of selling a published version. I believe it was most often a matter of sending a copy of the published music to Washington, where it was stamped and added to that year’s registry of copyrighted music.

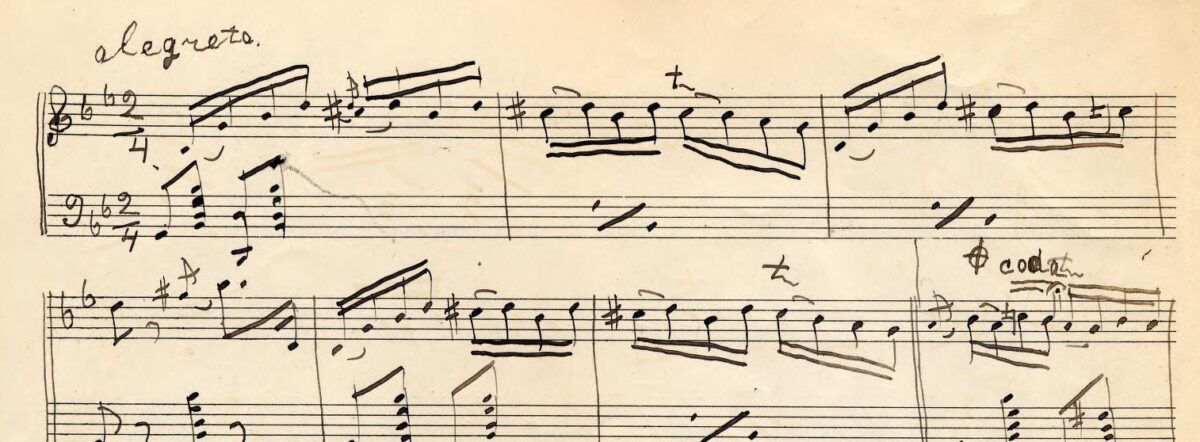

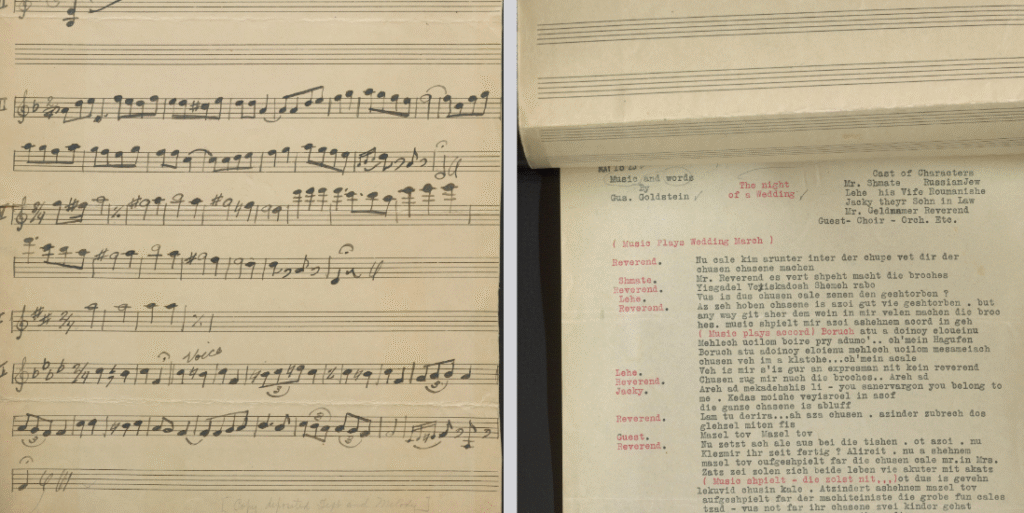

With the rise of the recording industry, this practice expanded to also include handwritten music manuscripts (sometimes with lyrics) which were never commercially published. Instead, these documented melodies or performances which were to be recorded on 78 rpm disc: a very basic score with a title matching the recording, and the name of the composer/arranger, with a date and number stamped on it by the copyright office.

Because of this connection between copyright manuscripts and recordings, if the historic recording is already available to us, it’s not exactly a case of uncovering lost music. In fact, the very plain score may be a worse way to learn a dance tune than listening to the recording. But seeing the score and reading the lyrics is still helpful for understanding and performing the music. It can also reveal which artist was behind a particular recording which may have been released under a generic record company orchestra label, or a partner who was involved in the arrangement or industry side of things but was not credited on the disc label.

In the klezmer world, we’re lucky that the Library of Congress has a special digital collection called the Yiddish American Popular Sheet Music collection, which contains almost 1500 published scores and copyright manuscript scores. Sadly there is no equivalent for Ukrainian music, which is very poorly represented on the LOC’s digital collections (as are most other heritage musics). But the scores exist in paper form and can still be called up and scanned in person, or ordered for a fee by anyone willing to pay. I’ll explain how, but first I want to explain how to know what to look for.

The early Ukrainian folk music recording industry in the U.S.

I won’t try to give a complete accounting of the Ukrainian folk music history of the U.S. I’m just thinking about my corner of it as a fan of old Ukrainian fiddle music and as someone who has been researching immigrant Jewish musicians who recorded for multiple ethnic markets.

Ukrainian music scores copyrighted by immigrant Jewish musicians, as with the Abe Schwartz score above, are more accessible than those of immigrant (Christian) Ukrainian musicians from that era. Those Jewish musicians—mini-celebrities of the old New York klezmer world like Schwartz, Naftule Brandwein, and Lt. Joseph Frankel—recorded hopaks, kolomeikes, Ukrainian folk songs, etc. with their Jewish orchestras, often in the same session as recording Jewish dances. In other cases, Ukrainian-born Jewish singers like Meyer Kanewsky recorded Ukrainian-language songs under a pseudonym, which were sold to a Ukrainian audience.

Abe Schwartz in particular copyrighted hundreds of non-Jewish dance tunes and songs due to his role at Columbia Records after WWI, leading bands playing ethnic music for multiple markets but also in identifying and bringing on new talent. In the Max Leibowitz vs. Columbia Records court case (which I hope to write about another time), it’s made very clear that dance melodies were identified as upcoming recordings, and Schwartz sent in the paperwork and sold the rights to the record company. In most cases he had not composed them and was simply trying to give the company a strong claim to what they were recording.

From the little I understand of the Ukrainian music industry in New York, non-Jewish bandleaders and soloists started to become more prominent by the mid-1920s. Pawlo Humeniuk made his first record in 1925, soon followed by the vocalist Eugene Zukowsky and others. A wider range of Ukrainian music was recorded by these musician than their Jewish predecessors, due to the particular tastes of the artists and audience: comic scenes in Ukrainian, village fiddle music, etc. But I wouldn’t see the two trends as being completely distinct or in competition. Industry middlemen figures like Schwartz seem to have worked with, and submitted copyrights for, Ukrainian recording artists well into the 1930s and 1940s and many of the recordings of the Ukrainian artists found a market among immigrant Jews as well.

How to identify and order scores

There are a few steps to identifying and ordering copyright music manuscripts from the LOC. Basically:

- Identify a 78rpm recording, type of piece, arranger or recording artist

- Search it in the U.S. copyright registers

- Make a note of the composer, title and number and fill out a digitization request form with the Library of Congress

- Weeks later, pay the final digitization fee and get the scanned scores through a filesharing service.

Identifying a Recording or Artist to search for

Because of the cost and staff time involved, I recommend doing a wide search to figure out what exists, and then narrowing it down to a dozen or two scores to order at a time. Here are some places to look:

Music streaming platforms & old recordings

Hearing digitized versions of 78rpm records and poking around online is exactly how I got onto this whole thing of ordering klezmer copyright manuscripts. I don’t think there’s one centralized place to find all of the Ukrainian American 78rpm discs digitized and streamable. Aside from commercial streaming platforms, reissue CDs like Ukrainian Village Music, and youtube, there is UAlberta’s digital collection of old Ukrainian music and the Internet Archive’s Ukrainian audio selections. Like I said earlier, the title of the 78 rpm side usually matches the copyright because of the business reason for submitting it. Just remember that they have to have been recorded in the U.S., not Canada, the U.S.S.R., etc.

Record Company catalogues

Record company catalogues were pamphlets or booklets sent out in the 78 rpm era so people or stores could know which new records were available for order. There were general annual catalogues by label (Columbia, Victor, etc.) and each one also put out monthly pamphlets aimed at particular ethnic markets: Jewish, Romanian, Greek, Ukrainian, etc.

There isn’t one centralized place to view all of them. But, because they were mailed out all over the place, they appear in many digital collections. The New York Public Library has this excellent LibGuide which lists many places to find them. In these lists you can get an idea of what was out there.

Discography of American Historical Recordings

The Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) is an amazing resource for trying to explore and contextualize 78 rpm recordings and musicians from that era. It’s worth searching by dance types (eg. kolomyjka, hopak), personal names (eg. Pawlo Humeniuk), or Marketing Genre (eg. Ukrainian, Ukrainian-Ruthenian).

Spottswood volume 2

If you can find it in a library, Spottswood’s Ethnic Music on Records Vol. 2: Slavic will also have a very thorough listing. There is a partial preview on Google books.

The information is similar to DAHR, which sources a lot of its info from Spottswood.

Searching in the Copyright Registers to see if it exists there

After you get an idea of what you want to look up, you have to find the entries in the copyright ledgers, thick books which were printed several times a year by the U.S. copyright office. Music copyrights were listed in their own volumes separately from other types of items. The entries are generally written in the latin alphabet (which can cause problems with transliteration) and are organized alphabetically by the title of the copyrighted piece. Not every recording is copyrighted in this way, especially if they were a redo or imitation of something which had already been recorded and copyrighted. Ignore the renewal or recording notices; you want to look for the original copyright submission which will have numbers like E 652946 or E unp. 73121.

Although they exist in print form and on databases like HathiTrust, in my opinion the easiest place to search old U.S. copyright registers is on the Internet Archive. There’s a special collection called Copyright Registers where they are all digitized and searchable. Select “search text contents” and start looking up keywords. It will highlight the digital results in each book for you. Keep these open in a tab if you want them because it’s easier to copy and paste from this search pane later.

When I was looking for klezmer copyright scores, I also searched for typical dance genres, keywords (Jewish, wedding, etc), likely typos and alternate spellings, and so on. Such keywords might bring up other similar music copyrights you weren’t aware of (including ones that never ended up being recorded). And it’s worth spelling transliterated terms in multiple ways. For example, we get different results by searching for kolomyjka, kolomeyka, and kolomeika.

Ordering the scores, payment & receipt

When you have a list of scores, you have to contact the LOC’s Duplication Services. (Or, if you live in the D.C. area you can go and scan them in person for free at the Performing Arts Reading Room, but you’d have to negotiate with them in advance as the materials are not held on-site.)

Download this PDF Duplication Services Order Form and fill out a new form for each 10 items you request. Then email the PDFs to DuplicationServices@loc.gov and it’ll get the process started. With an official request, the Duplication Services will call up the boxes and look for specific scores for scanning. I recommend Digital Photocopy (PDF) which costs $1.50 per page (plus research fees if applicable); you don’t need expensive high resolution scans for this purpose. All the scans I got at that quality were very legible. In some cases the initial estimate was much more than the final cost I was asked to pay.

They may email you to ask for clarification, and with the 3 times I’ve ordered, it’s taken weeks for them to get back to me with the actual files. They generally can’t find all of the scores; they just charge less and indicate which ones they couldn’t find. For my three orders, I paid $38 for my first order of 15 items, and $155 and $185 for my later, much larger orders of ~45 items. The last one was in early 2024 so the price may have changed by the time you try it. The files are sent by a time sensitive dropbox-type service called Media Shuttle.

Conclusion

It’s a strange process, but I think this method is worthwhile for digging up old folk music scores which were never published and are spread out among random boxes in remote storage somewhere. It’s especially helpful when trying to piece together a song or comedic performance in dialect which you’ve only heard on an old scratchy recording. But I’ve also found it interesting to see how the klezmers from back then wrote down their handwritten scores, even if I’ve heard the recording many times. It makes me see the shape of the melody in a new way.

The examples I gave here were for Ukrainian fiddle music, but I think the same approach could be used for other types of heritage music which were recorded and copyright in the U.S.

Dan Carkner