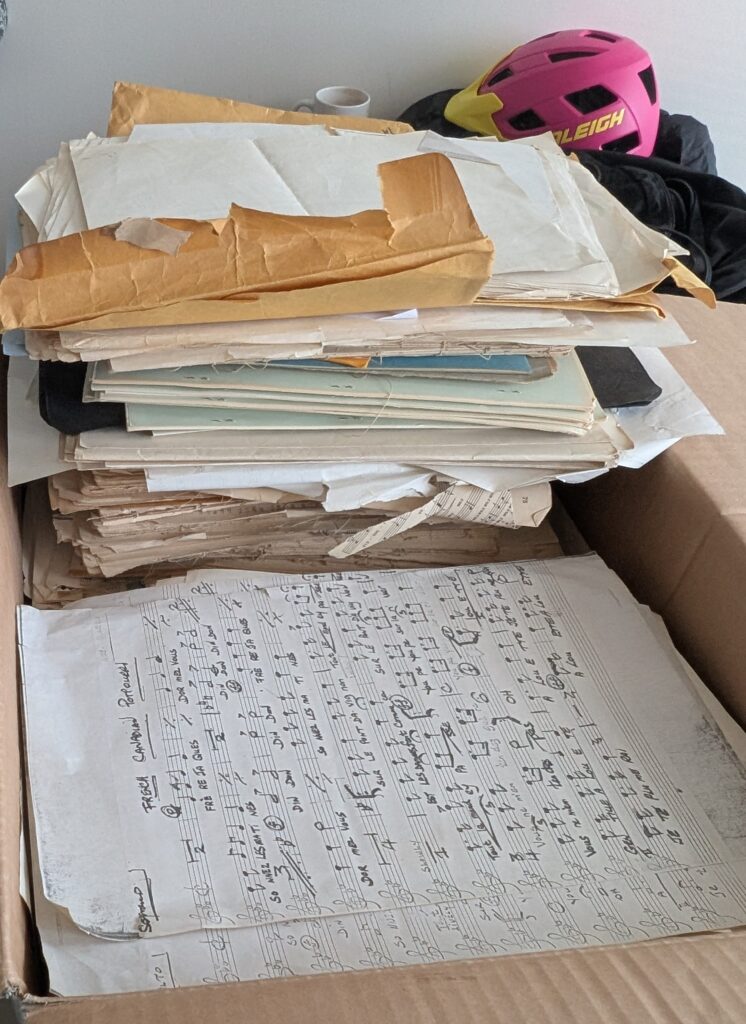

This past spring, I stopped by Montreal for a few days on my way back to Vancouver. Josh Dolgin, better known as Socalled, invited me to his office at McGill University to look over some Yiddish choral scores he inherited when the former Montreal Arbeter Ring (Workers Circle) building was being emptied out. The boxes of loose and tattered scores were a relic of the Workers Circle choir which operated in Montreal from around the 1930s to the 1990s. Lately I called him up and asked him some questions about it.

D. Tell me how you came into possession of all these scores.

J. A friend named Avi said to me, “hey, you know, there’s this building that’s closing, a Yiddish cultural building.” And I kept running into people who were saying, “oh yeah, I’ve been to this building that’s closing.” I had a party and they showed up with stamps from the building, cards, and books. They were taking stuff from this Yiddish building that was closing. I had never heard of it. It was the Workman’s Circle!

Um… Actually, now that I think of it, I realize that about 25 years ago, I did a concert there. But anyway, it wasn’t really on my radar. And it wasn’t on the radar of the Yiddish scene, as far as I knew. Like, the so-called New Yiddish scene. KlezKanada had never done anything there. The Yiddish Theatre had never done anything there. It seems like it was its own little world of the Worker’s Circle.

Now I know a lot more about the building and about the history of that organization, but … it was not on my radar of being involved in Yiddish in Montreal for 20 or 30 years. So, eventually, Avi’s like, “people are going to this building. There’s certain times when you can go and check it out. They’re trying to empty it out. They’re closing the building.” Okay, great. So I go one day.

D. And what year was this? Like, 2 years ago or something, or…?

J. Last year. Rivka Augenfeld was kind of in charge, and she’s in the scene, she’s a well-respected Yiddishist and translator and activist. Really awesome, interesting lady. And she’s at the building, and there’s this sort of chaotic emptying of this building that’s been there since the 50s. (Before that, it was in another location, it’s been around since about 1907.)

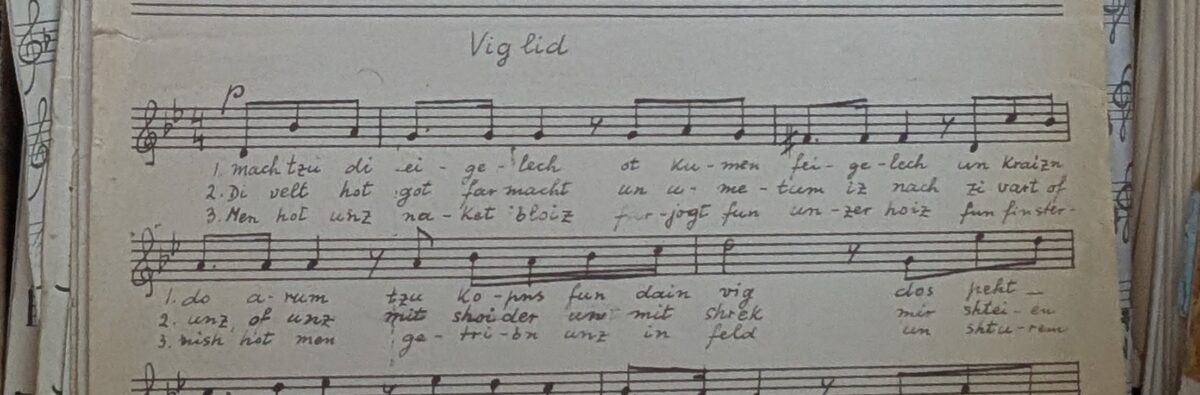

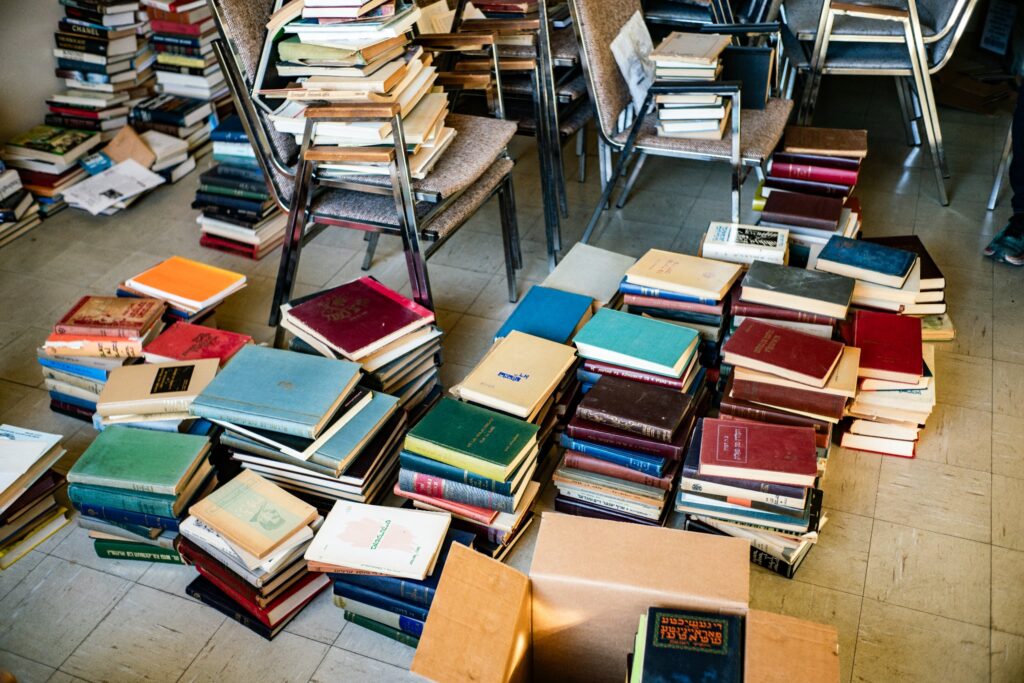

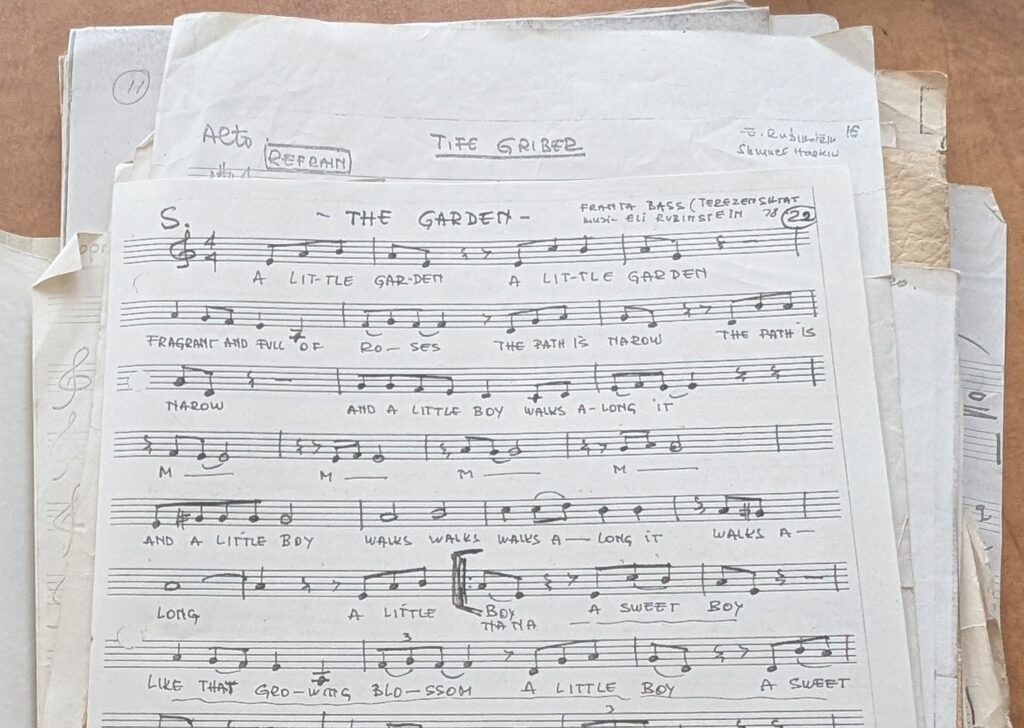

And so I show up, and there’s people going through books, and taking the shelves, and taking desks, and chairs, and it’s just like… this building that’s full of Yiddishkeit. Full of books, full of accounts of the burial organization, and a library of Yiddish literature and, like, all sorts of texts. And people are like, “oh, you gotta go upstairs and check out the closet. I think you’ll be interested in something in the closet.” So I go upstairs, and open the closet, and sure enough it’s full of Yiddish choral sheet music. From the Yiddish Worker’s Circle Choir. And all their papers are in total disarray. Basically stuffed into this closet.

And it’s in this room that was cool, it was named after these heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising [Erlich and Alter]. There’s portraits of them on the walls, and there’s a microphone, and a lectern, and a piano. And it’s like, they would have concerts there. And in the closet is this… this insane pile of papers, which you’ve seen. And basically, it was like, “oh, you want them? Okay, take them.” So, thanks to Rivka and Avi.

I bundled up the papers and took them home for a while, and then I realized, hey, this could be an amazing project for the students at McGill who I was planning to teach a class about archiving, Yiddish archives, and being a zamler. And about collections, going back to YIVO and the Strashun Library in Vilna. I thought, oh, wow, I could work it into this class, I’ll get the students’ hands dirty, actually, with an unorganized new archive of an incredible repertoire of Yiddish song based in Montreal.

D. And how does Maia enter into it? Because I tried asking her about it, and she said, “oh yeah I was there too!”

J. Maia from the Jewish Public Library?

D. What’s that? No, this is Maia from Brivele [a Yiddish music duo from Seattle].

J. Oh, right! Yeah, so… she knew about it before I did. Like, a bunch of people that weren’t even from Montreal at all were like, “oh yeah, I’ve been to this building that’s closing.”

Josh and I discussed various people who had come in and looked at the things in the Workmen’s Circle building, including people who happened to be in town for KlezKanada in August 2024, and local Yiddishists.

J. They were in contact with the Jewish Public Library. So the Jewish Public Library came in and did a pass, and took probably the coolest stuff.

D. Yeah.

J. The most beautiful books. The most beautiful portraits from the walls, I hope. But they had a pile for the Jewish Public Library, so that’s good that it went to them.

There was another group of… uh, do you know Shlomo? There’s this person named Shlomo who is really awesome, a kind of religious Yiddishist. Who, I think just graduated from translation program at McGill, a young person, but super dedicated. So Shlomo was sort of collecting a ton of stuff that would stay in Montreal.

I saw what was going on, and I saw that it was a bit haphazard. And that there was more material than any one person could take. Even if, with the best of intentions, they wanted to keep this stuff. So I got on the phone with Aaron Lansky down to the Yiddish Book Center, and I said, yo, there’s this Worker’s Circle place closing, and it’s packed to the rafters with Yiddish books. Uh, can you help out? And he said, oh, sure. And so he paid for the rental of a van, and Avi and I drove about 600 books down to the Yiddish Book Center. So at least that’s together in one place down there.

And then, after I sort of saw that there was a collection here, at least in the choir department. It would be cool if it was all kept together. If at least there was one copy of everything … I put out a call saying, hey, everybody who was there taking [music] stuff, could you just send it to me so I have a copy of everything, and I’ll send everything back to you. There’s copies of everything, so probably I have another copy, but there are also handwritten things.

D. Yeah.

J. So I just wanted to have the handwritten, original copy of each piece of paper. And frankly, I mean, I guess we’ll get into this, it’s a kind of a huge job that I’ve only scratched the surface of with this one term with my students, and just working by myself. To try to establish just what is in the thing. Like, that’s sort of the… to me, the first step is to just get a copy of everything, put it in alphabetical order. And then know what we’ve got.

D. All right, so… You got it, and then you brought it to McGill, basically, and then… who have you talked to? Because I think you mentioned a while ago that you talked to different people after you had it, and you wanted to make sense of it. People who were maybe around back then, or who knew about it?

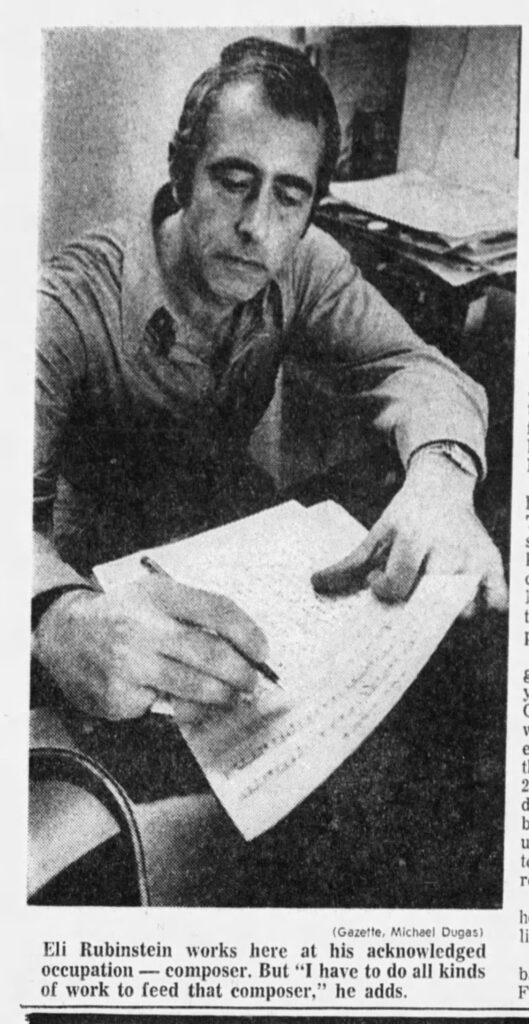

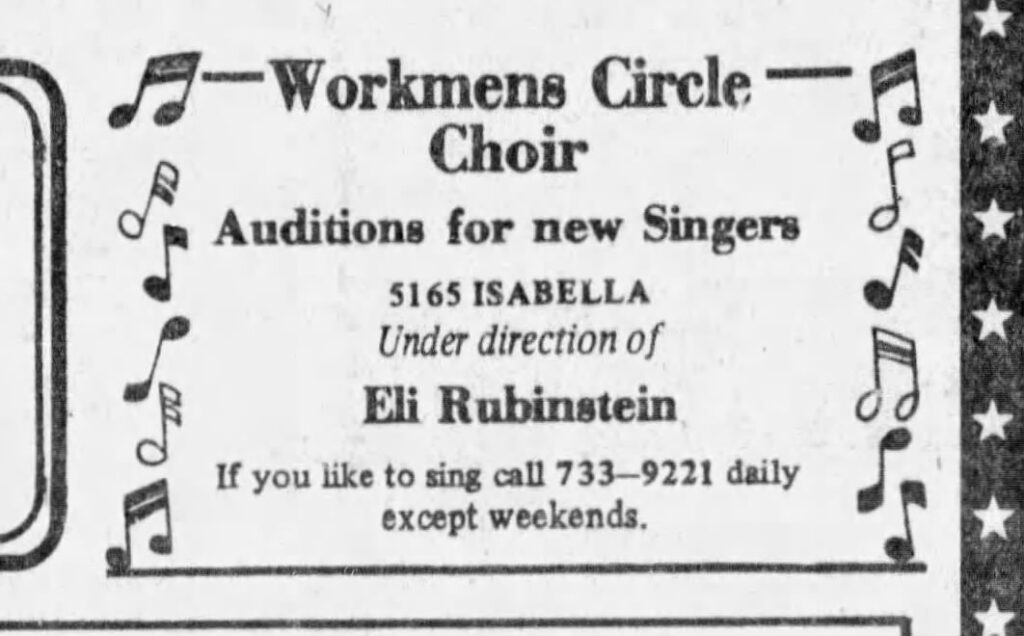

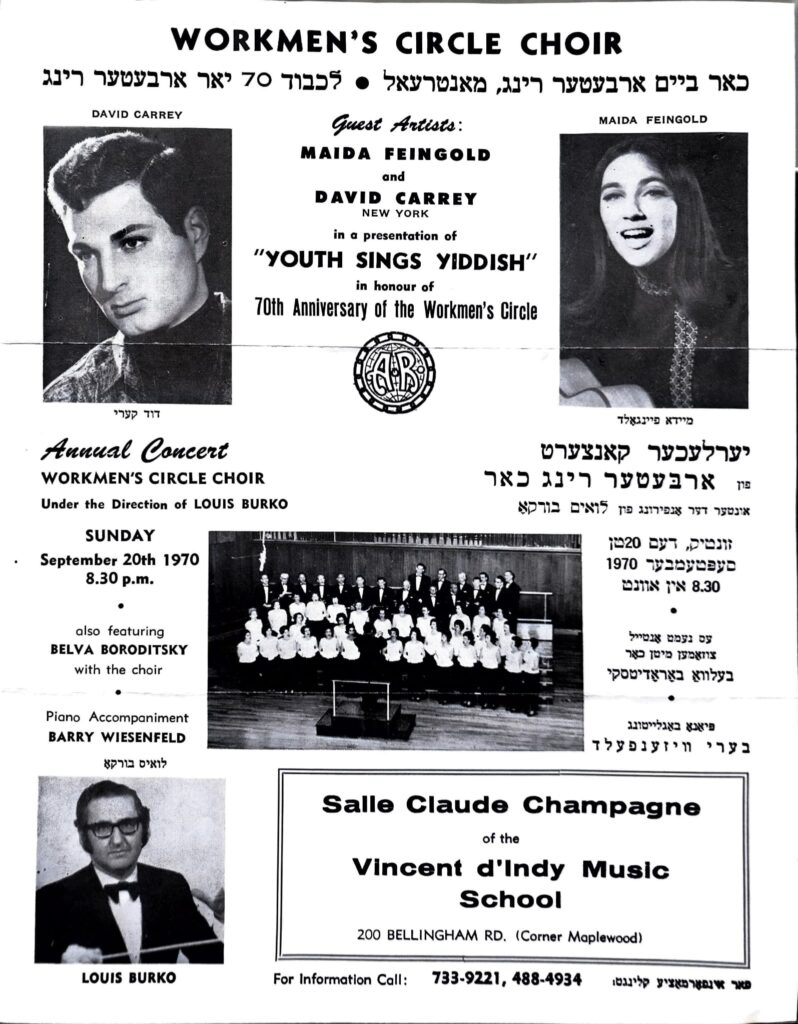

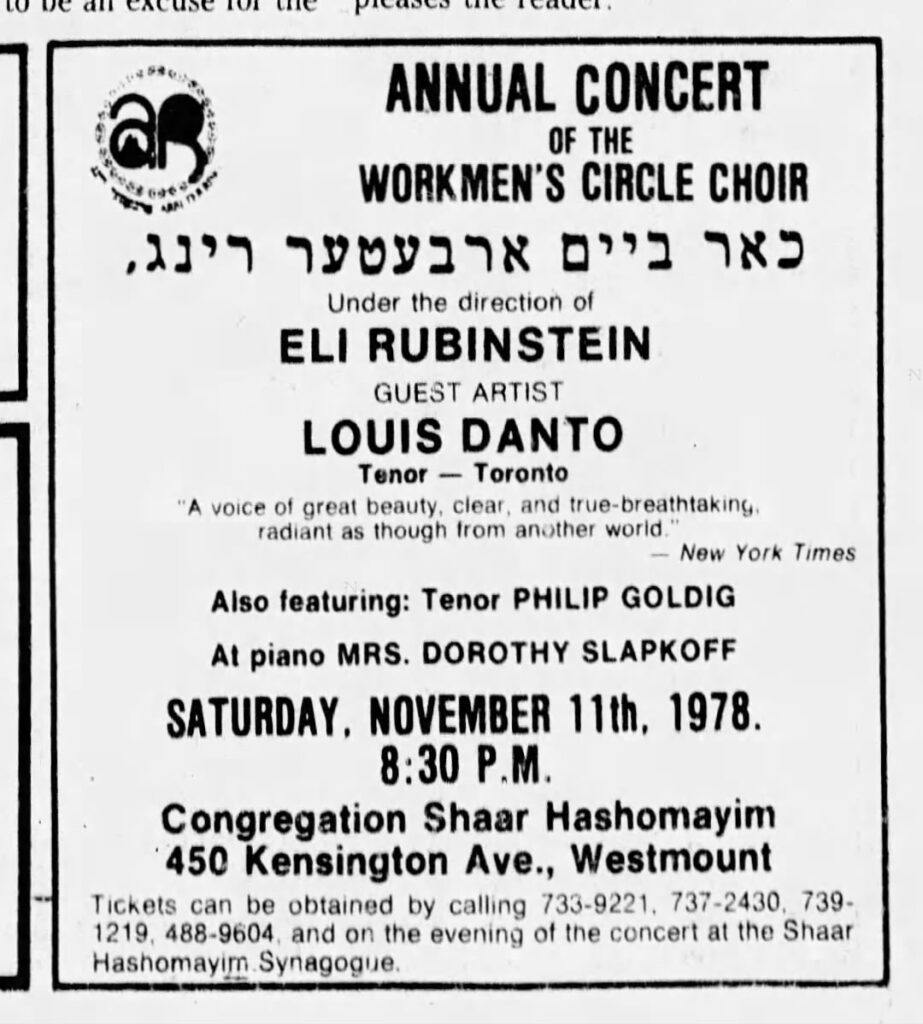

J. Right. Well, looking through the collection, I pretty quickly realized that there were basically two main choral directors over the course of the choir’s existence. A guy named Louis Burko, and a guy named Eli Rubinstein. Or Rubinshtayn. So, I tried to track down any information about either of those two people.

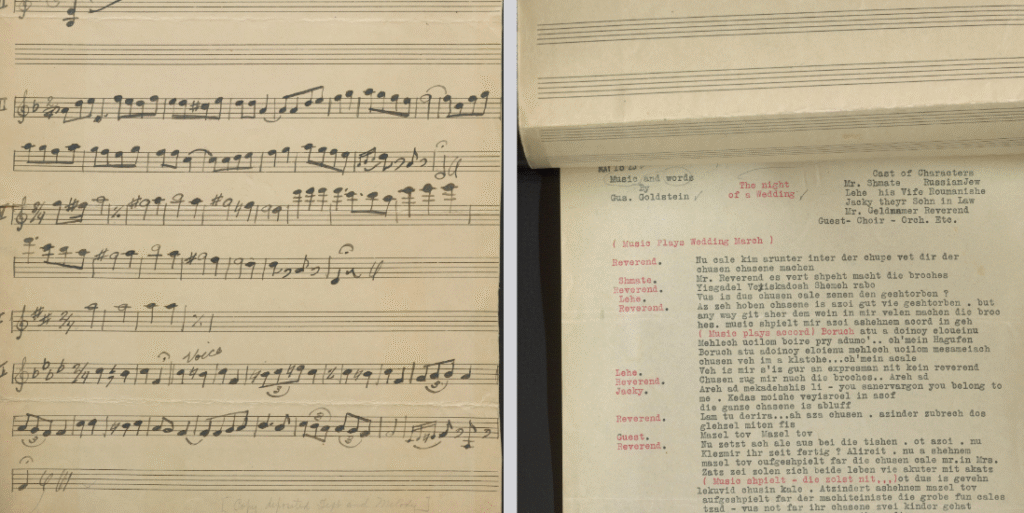

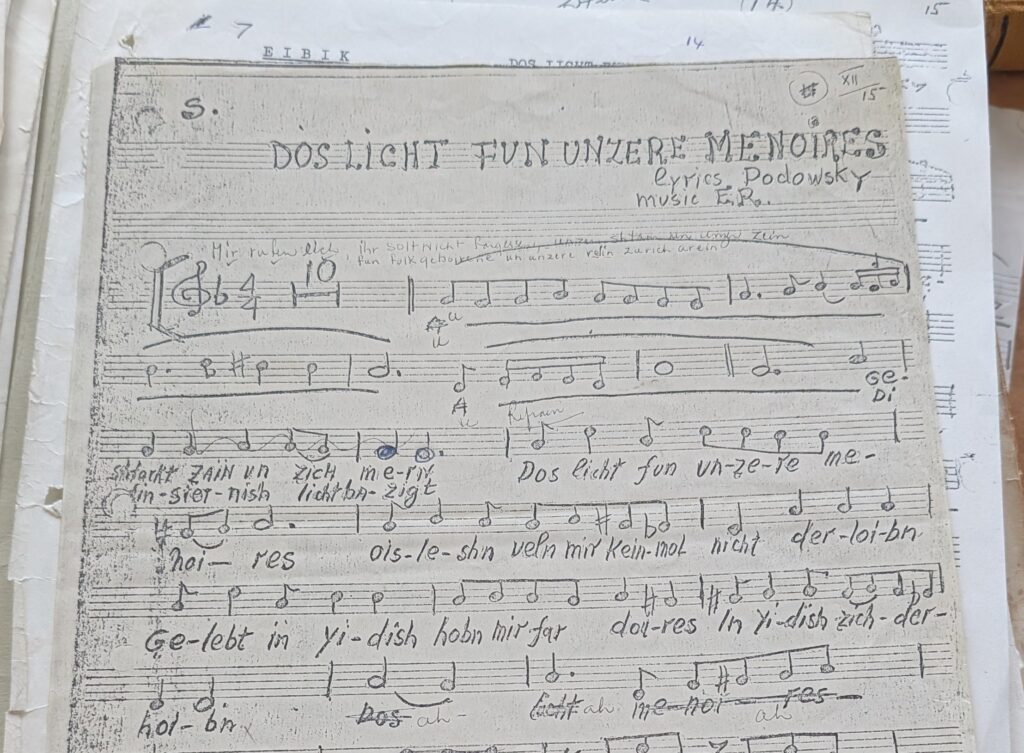

Eli Rubinstein was a very prominent voice in Montreal Yiddish music. Like, professional Yiddish music, or even kind of amateur Yiddish music. Whenever there was a choir, he was involved. And he was the main composer, the sort of in-house composer for the Montreal Yiddish Theatre. So there’s pictures of him, there’s his works, there’s a bit of a trail from him. Especially at the Montreal Yiddish Theatre archive. They’ve got a whole Eli Rubinstein collection there, photographs of him. Unfortunately he passed away. His wife is still alive. I’ve tried to track her down.

Through this whole process of me being not from Montreal and being interested in Yiddish music. It’s just been kind of amazing how compartmentalized every little subset of the scene is, and how nobody talks to each other, and how everybody kind of protects their little world. I mean, just the Workers’ Circle building, like… There was this whole building that none of us knew about, and that we could have been doing concerts at. We could have been working with older people, working with survivors, and working with members of the Bund and stuff. We would have been very interested to do that. And keep the building, you know, and keep it going. There’s a revival of the interest in this. In this culture, the poetry, the philosophy, the literature, the music.

D. Yeah.

J. Actually, we could use—Montreal could use—a place like that.

Um, okay, so… Rubinstein. He’s a very interesting character. You can look him up. From Romania, went to Israel for a few years. Almost 10 years, maybe, where he had big success. Like, with a radio orchestra, and writing hit tunes and stuff, he wrote this hit tune called, uh… Lach Yerushalaim. Which is an awesome, like. Camp… kind of campy, kitschy, early 60s Israeli pop song. It was a big hit. It’s been recorded by a million artists in Israel. Like, people really know that song.

And then, somehow, and I don’t know why, because I didn’t get to speak to him or read any of his papers or anything: for some reason, he moved to Montreal, where he right away met the Yiddish Theatre lady here, Dora Wasserman. The famous Dora Wasserman. And they hit it off, and he was a very professional musician and composer, so it makes sense that he met her.

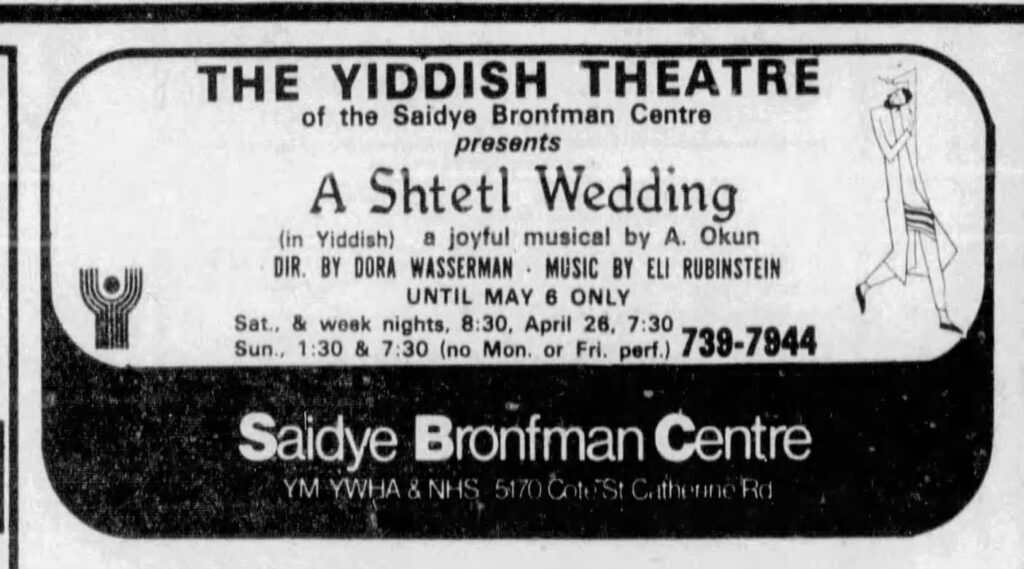

He was looking for work in the Yiddish world, the Jewish world, and so he right away started composing for Yiddish Theatre. Wrote a ton of songs and a ton of shows for them. The apex of that was a show called A Shtetl Wedding, which is a full musical. You might have the vinyl of it, because I find that record everywhere.

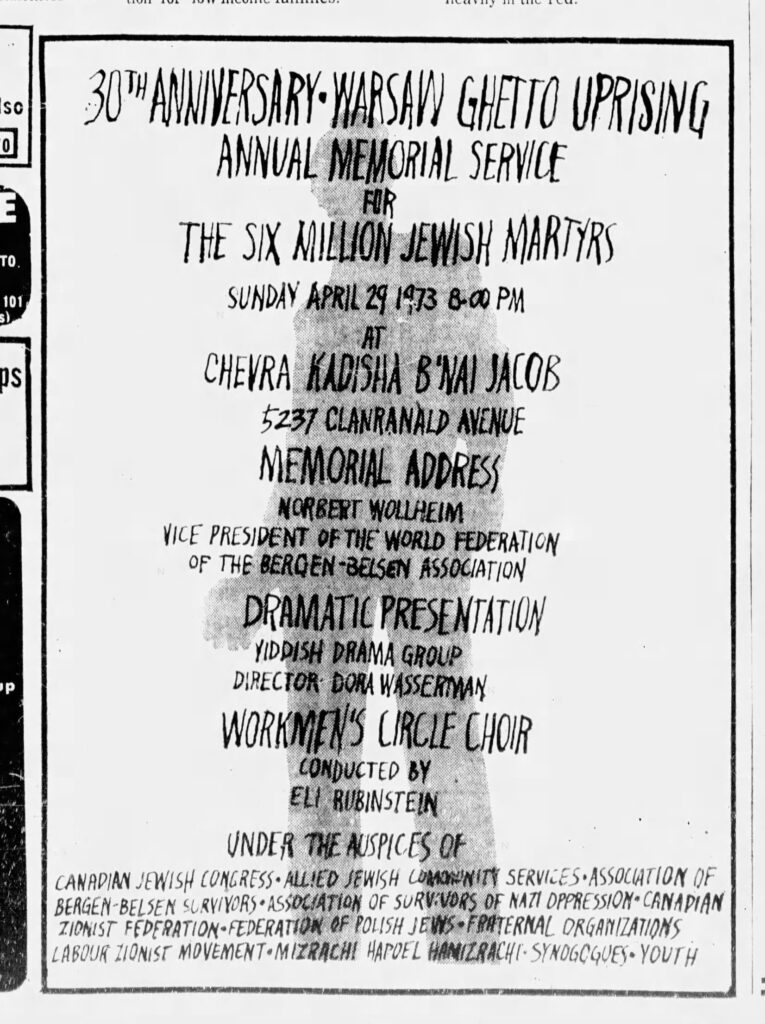

D. No, I don’t have that, but I found newspaper advertisements for it when I was searching his name, it’s just, wall-to-wall. Big advertisements, so you can tell it was a big deal. And ads for him leading concerts, for the Worker’s Circle Choir, for this choir, and for that choir.

J. So yeah, that’s Eli Rubinstein. And, till recently, I guess, probably till the 80s, at least, and the 90s he was still working at it. Uh, he eventually got trained as, a… I think a dental technician or something? He got some real job, finally, and so he started being less active, you see him, sort of, being less active in the choir world.

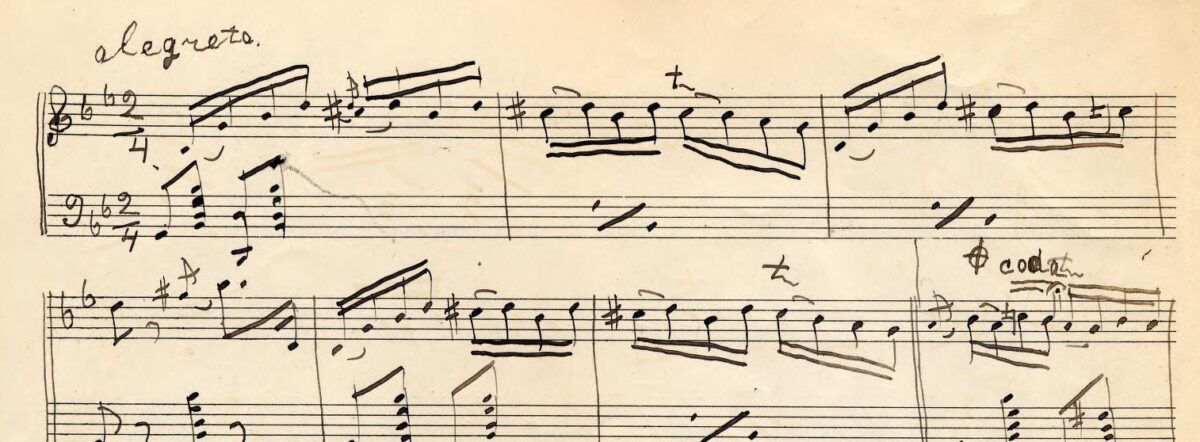

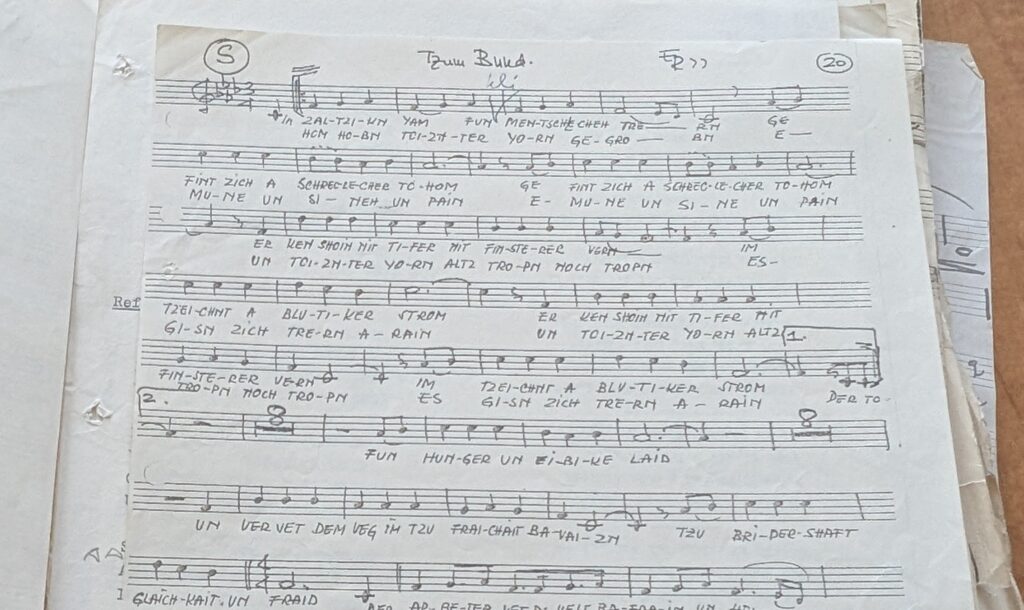

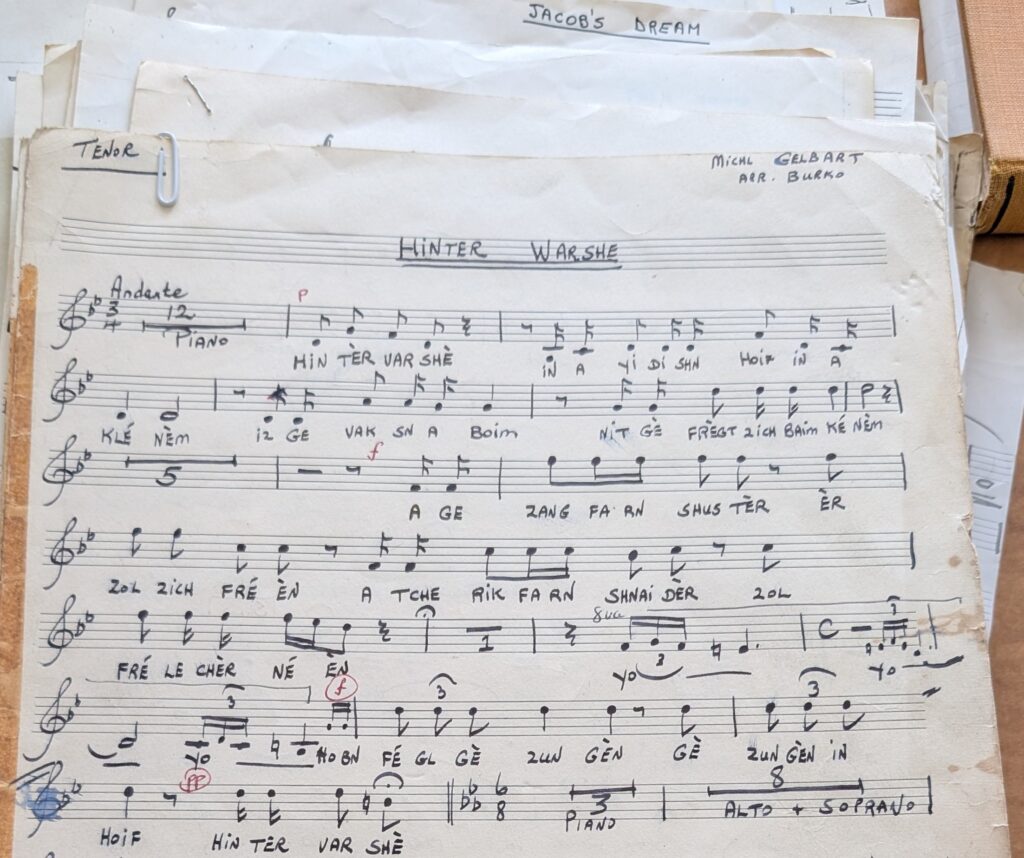

Um, so that’s… that’s one of the handwritings that I see a lot of [in the choral scores].

But before Rubinstein was a guy named Lou Burko. And his handwriting is beautiful. It’s really juicy, and just assured and clear. And he was a super trained musician from…

D. Yeah, I found a bit about Burko, he studied music somewhere, in Canada or the US, right? Like, in the 50s or something, right?

J. Yeah, I think at McGill. Right. In the 50s, but even before that, I think he was born in Poland. But yeah, came to Montreal pretty soon, and studied.

(We consulted the notes from Burko’s son, and it seems he was born in Poland in 1931 and was brought to Montreal as an infant.)

J. He really was kind of a frustrated conductor. And composer. He would have been happy to be Leonard Bernstein. I think he studied with Bernstein, at Tanglewood. He was a young conductor there, I think studied under Bernstein for a second.

So, I managed to track down his son Benji Burko. He was happy to talk to me about Lou Burko. I did a whole big interview with him. In fact, I could send you that, if you want.

D. Sure. Yeah.

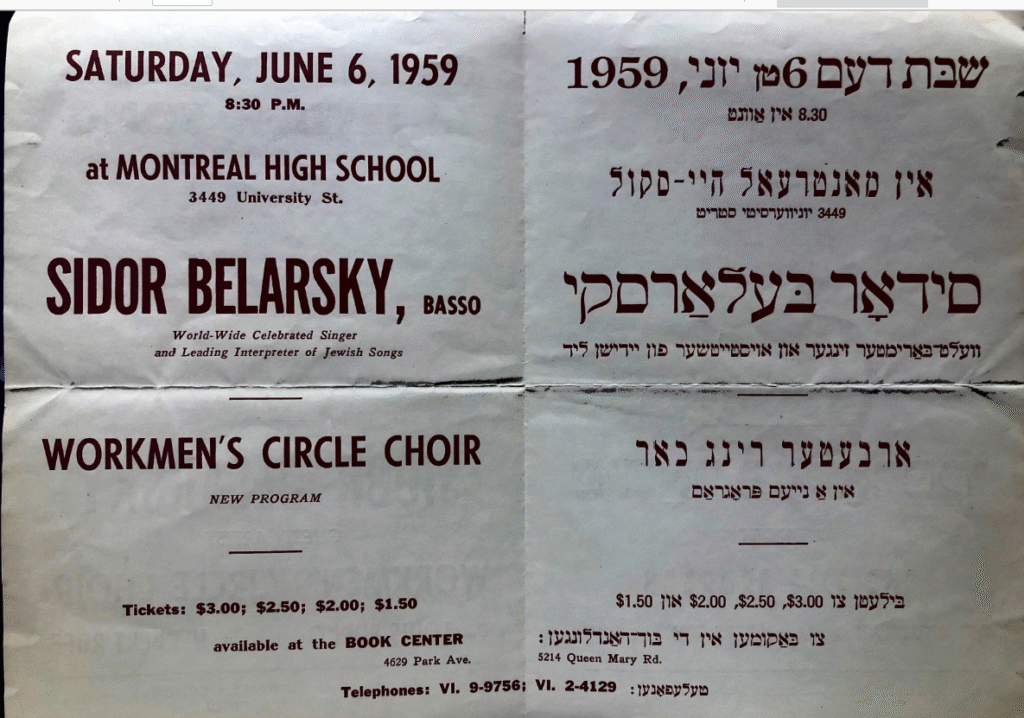

J. Very nice guy, also musical. So, Lou Burko was the conductor before Rubinstein. Probably the height of his tenure there was during Expo 67, when the Worker’s Circle choir performed at the Israeli or Jewish pavilion, I’m not sure what it was called.

Burko, you’ll hear from the interview, was slightly frustrated by the Worker’s Circle choir, because it was an amateur choir, and he was a serious cat, and he wanted to be a real conductor. So, working with these amateurs was a little bit annoying for him, but he worked it with a bunch of choirs, and it was handy also because he could get 100 voices together if he needed to. He’d get these enormous choirs together, putting together the Worker’s Circle choir with the other community choirs and stuff like that. And then eventually, he got a job at a synagogue. [Shaare Zion. -D.]

He worked there for 40 years, and that was sort of his main bag. He wrote a ton of music, they published a book of his songs.

D. So what kind of songs are these?

J. He was absolutely a beloved choir director there. Uh, so those are settings of cantorial pieces and synagogue music. Um, but here, for this [Worker’s Circle] choir, he’s writing charts for Yiddish songs. Four-part harmony charts.

One step that I’m getting to is putting a paperclip when I get four parts, when I get all 4 parts … but until then, it’s just a sea of papers. And really, it’s like somebody shuffled the papers, you don’t find things that go together. But then as you’re going, it’s like, oh, hooray, here’s a soprano part for Arum dem Fayer… and then finally, you get all four parts, it’s very exciting.

So those are the two main conductors and arrangers, but I do know that there were other ones. Which I managed to piece together, based on programs. I think you probably took pictures of the programs?

D. Uh, just one or two of them, actually.

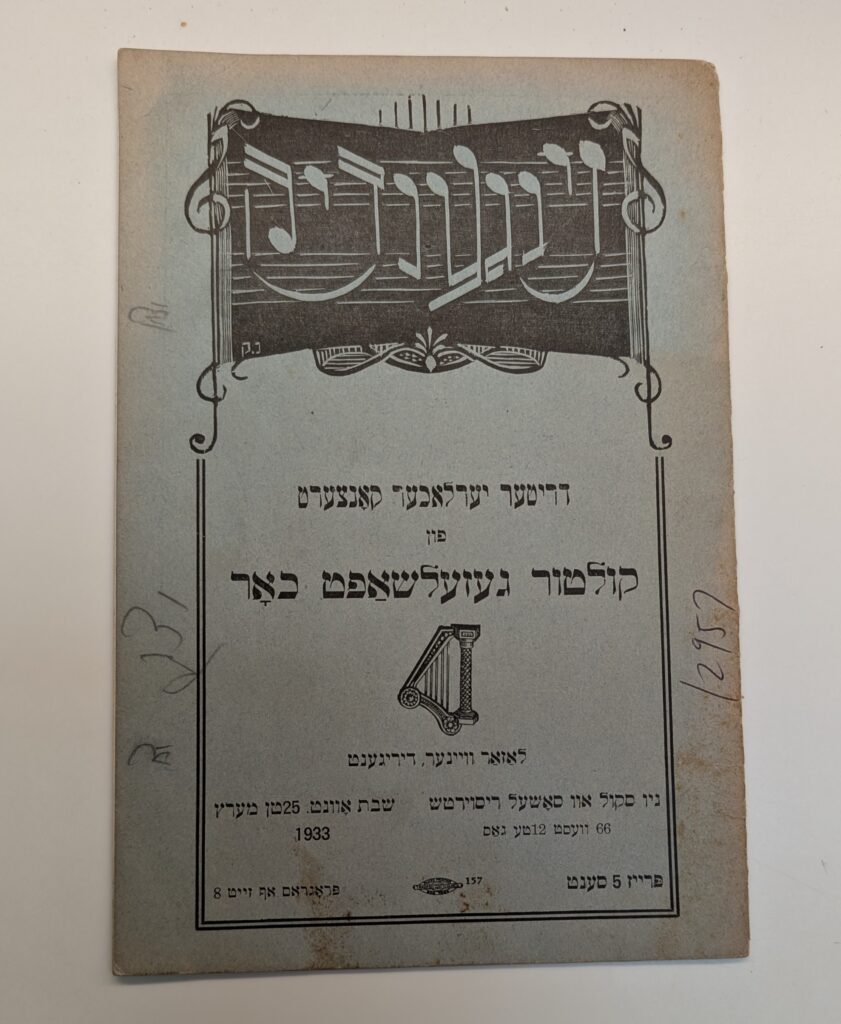

J. Yeah. And… those only really start in the sort of late 60s. But I’m pretty sure the choir, and maybe we could go more into this, I’m pretty sure the choir started at least in 1937. That could be when the choir really started.

The Arbeter Ring started in Montreal in 1907. And there’s a program saying the 20th anniversary of the choir, I think that’s 1957. So I think it started in 1937. And then I think that history is sort of tied into the history of the buildings, which I am also trying to piece together. Basically, the first building was on St. Laurent, where the Sala Rossa is now. The Sala Rossa… became a Spanish cultural center, but before that, it was the Worker’s Circle Building.

D. Yeah.

J. And it was a whole… like, it was a universe of activity. There were schools there, there was a gym. There were choirs, there were classes for adults and kids, and a kindergarten, and offices for the Bund and offices for this and that, I still cannot wrap my head around all the sort of competing forces of Jewish socialism. Were they communists? That were Zionists? Were they Zionists that were anti-Stalinists? Were they… like, there’s just all these great gradations.

Eventually, it sort of, I think, gets… like, simplified. And the Worker’s Circle building that I went to that was closing had such a vast spectrum of books from, the most Zionist books to the most anti-Zionist books. From the most, secular Yiddishist books to absolutely religious books. So I think people just sort of… As the population shrank, and as people left Montreal, I think it did consolidate a lot of those competing interests.

But I’m still just trying to wrap my head around that. And the camps, there’s a camp for this, and a camp for that, and a camp for not this, and not that, and they all… they broke up. They broke up at a certain point. Like, the Camp Kinder Ring, or whatever. I don’t know.

The best book about [secular Yiddish choirs]. Marion Jacobson. I don’t know if you know that name. Wrote the book on labor choirs, like, the labour, Worker’s Circle, Bund choir movement.

D. Did she write a thesis about it or something, right? Is that her?

J. It’s … it’s a thesis, it’s not a book, unfortunately, but it’s a thesis.

D. Yeah.

After talking about getting me a copy of the thesis, Josh turned to talking about his impression about how this choir fit into other Yiddish art choirs, especially more famous ones in New York City.

J. Like… what’s the word? I’m looking for? Uh, when you’re a snob. Like, there’s… there’s this, snobbery in the discourse of Yiddish song, like what’s serious Yiddish song? What’s a real choir, you know?

D. I see.

J. Like, you know… what’s his name? Like, Vladimir Heifetz, and Maurice Rauch, and all these sort of serious musicians.

D. Yeah.

J. And serious professional choirs, they sort of poo-pooed and looked down on these Worker’s Circle community choirs. By today’s standards, I bet these community choirs were amazing. Like… you know, they would have had a very professional accompanist playing the charts, they would have really practiced… everybody would have known Yiddish, they would have had these incredible conductors, Rubinstein and Burko. For example in Montreal were these incredibly trained, you know, top-notch professional musicians, probably in the choir there were a ton of trained singers.

So it’s just funny to see what’s considered serious music as we go along. Now we have these sort of… really ragtag choirs, where we put them together the best we can. People rehearse twice a month, if you’re lucky, or something. But just in the discourse, in the literature, there’s barely a mention of any of these choirs. Um, but this repertoire is interesting. So, sorry, what’s your next question?

D. Yeah, before you get into that, so, did you meet anybody who knew Rubinstein, who’s around, who’s not yet passed away?

J. Sure. I mean, do you know, Bronna Levy?

D. Not personally, but I know who that is, yeah.

J. Okay, so Bronna is a Yiddish singer from town, who I’ve known for 30 years. Like, when I first started getting into it, I met her, we had a band together. So, I’ve known her for 30 years. And she’s been in the industry. Since she was a kid. Her mother was in it. Her mother is on the Shtetl Wedding record. So they absolutely knew Rubinstein. I mean, all the old-school Yiddish Theatre people knew and can talk about Rubinstein.

Yeah, we used to sing one of his, a couple of his tunes. Because he writes really catchy tunes. A cool Rubinstein thing that I just happened upon by accident is that he sort of arranged and conducted this record by a guy named David Carey. Have you heard of him?

D. No.

J. Um. Who… I’m actually in touch with his brother, who is [Henry] Carey. And their mother was a woman named Layke Post, who was sort of tapped by Isa Kremer, of all people. To carry on Isa Kremer’s legacy, before she moved to Argentina. So, Layke Post is this incredible, trained opera singer who sang Yiddish songs. Really fucking awesome. I have a bunch of recordings of her.

And her sons also sang Yiddish songs. David Carey became a famous Yiddish singer in the 70s. Uh, which was a weird time to be a Yiddish singer, but he put out a record then, like this LP that is arranged and conducted by Eli Rubinstein. So he must have [known him]. I don’t know how they met, or how that happened. David Carey, you should look him up, died of AIDS early on, he was a victim of the AIDS epidemic. He’s really… exactly in that moment. In New York City, gay… died very young. Amazing singer. You’ll find his record, I guess, up on YouTube and stuff.

But yeah, there you go, and he’s on the back cover, Eli Rubinstein. So I sort of see him popping up here and there. I know Bronna Levy, she grew up hanging out with Eli Rubinstein.

D. And did you meet anybody who was in the choir?

J. That’s a good question. Um, no.

D. No? Okay.

J. I’ve asked people… Actually, just lately, somebody said, oh yeah, my grandfather was in a Yiddish choir, I’m pretty sure it must have been this choir. But no, haven’t spoken to anybody. Yeah. I mean, somebody that I would interview. There’s Anna. I don’t know if I really did a proper interview with her. This was her office, actually, at McGill. The Yiddish teacher at McGill. Anna Gonshor. Um, I’m sure Rivka Augenfeld, she might have even sung in the choir. And this guy named Saul [who was involved with the Worker’s Circle].

D. Yeah. So, when I was looking in the newspaper, like, on newspapers.com. All mention of the choir kind of disappears, in the 90s at some point. It’s like, there’s less and less notices—”oh, we’re playing this event,” and then it’s just, nothing. So is that how it comes across to you, that it just kind of fizzled out in the 90s? Do you know what I mean?

J. That’s about it. I found a CBC interview. Actually, at the Jewish Public Library. Um, I might have it. Let me see here… Okay, so anyway, it was basically the late… I think it might have been 91 or something. And it was a piece about the choir, and I guess Rubinstein was still conducting it. Um, yeah, and that’s it. I mean, it just kind of fizzled out in the 90s. Uh, I don’t have an account of that, of the demise of the choir. Really from anyone. I haven’t really done that kind of research for it, so I hope you find some shit out about what happened to the choir.

D. Yeah, I mean, that’s pretty recent, so you gotta figure there’s people around who were there, you know?

J. Right. Pretty recent, but even 35 years, there’s a lot of damage to people that are 70. In the 90s.

D. Yeah, but it’s not to say they’re necessarily that old at that time. They could have been in their 40s or 50s, you know?

J. Right. Eh. I think that’s why it went down, because they didn’t have younger people. They only had people from the real generation of the 50s and 60s, those are the people in the choir. You know what I mean? But don’t quote me on that.

D. Alright. Uh, what else? So, getting into the scores. What’s your overall view? If you were trying to explain what’s in the scores to somebody who hadn’t seen it yet how would you describe it? Because it’s quite a mess. But obviously you’re starting to notice stuff, right?

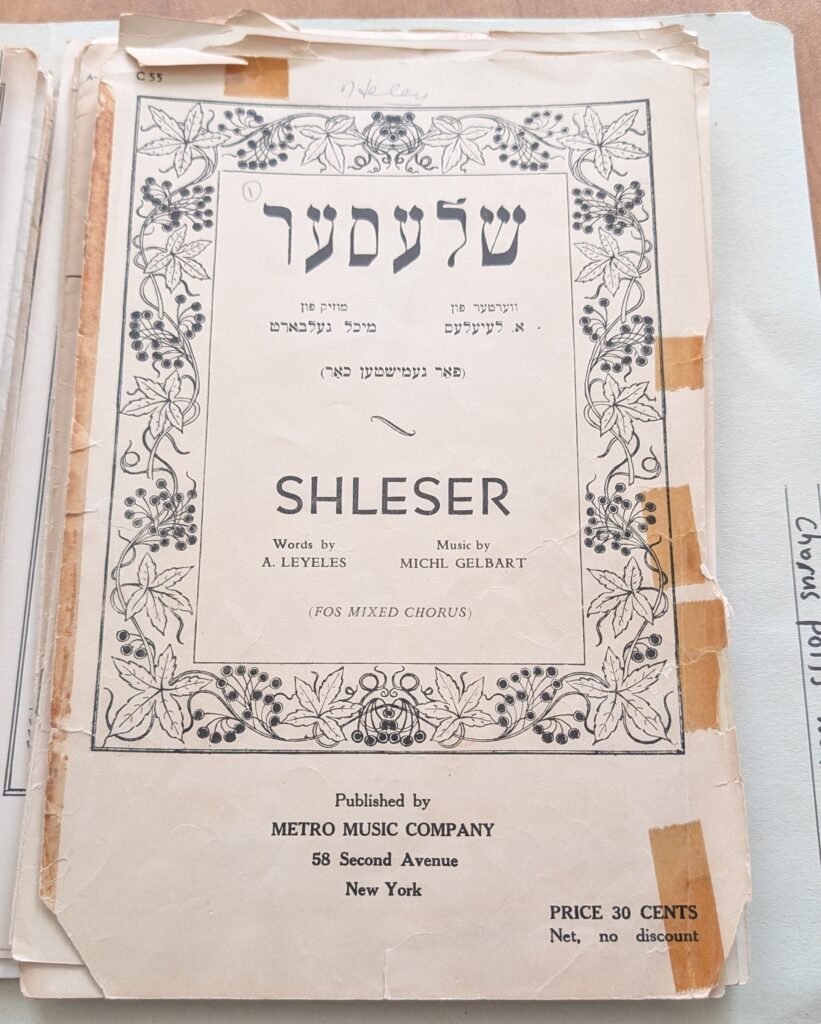

J. Yeah. I mean… Um, what makes this a unique collection. Are the original arrangements by the in-house people, by Burkow and Rubinstein. So that’s what makes it interesting, because, frankly, the repertoire looks pretty standard. It’s a lot of the Yiddish songs that you’ve heard of. I can’t say that definitively, because I’m just scratching the surface of the collection.

But from what I’ve seen so far, it seems to be a collection of popular Yiddish folk songs. Like, composers, songwriters that are important in the repertoire, like Gebirtig. Uh, or Warshawsky. But then there’s also settings of poetry that are probably original songs by Rubinstein. And Burko. More Rubinstein than Burko, I think. Burko had less…

D. Yeah.

He was less interested in being a composer. He was more about arranging and conducting. So there’s original music by Rubinstein, for sure, arranged for four parts. There is not one piano chart. There’s no accompanying parts. I haven’t found them yet. There’s still a huge box that I haven’t gone through, so maybe that’s in there, but maybe it was just that Rubinstein knew the parts and could play the chords and accompanied it, just like that.

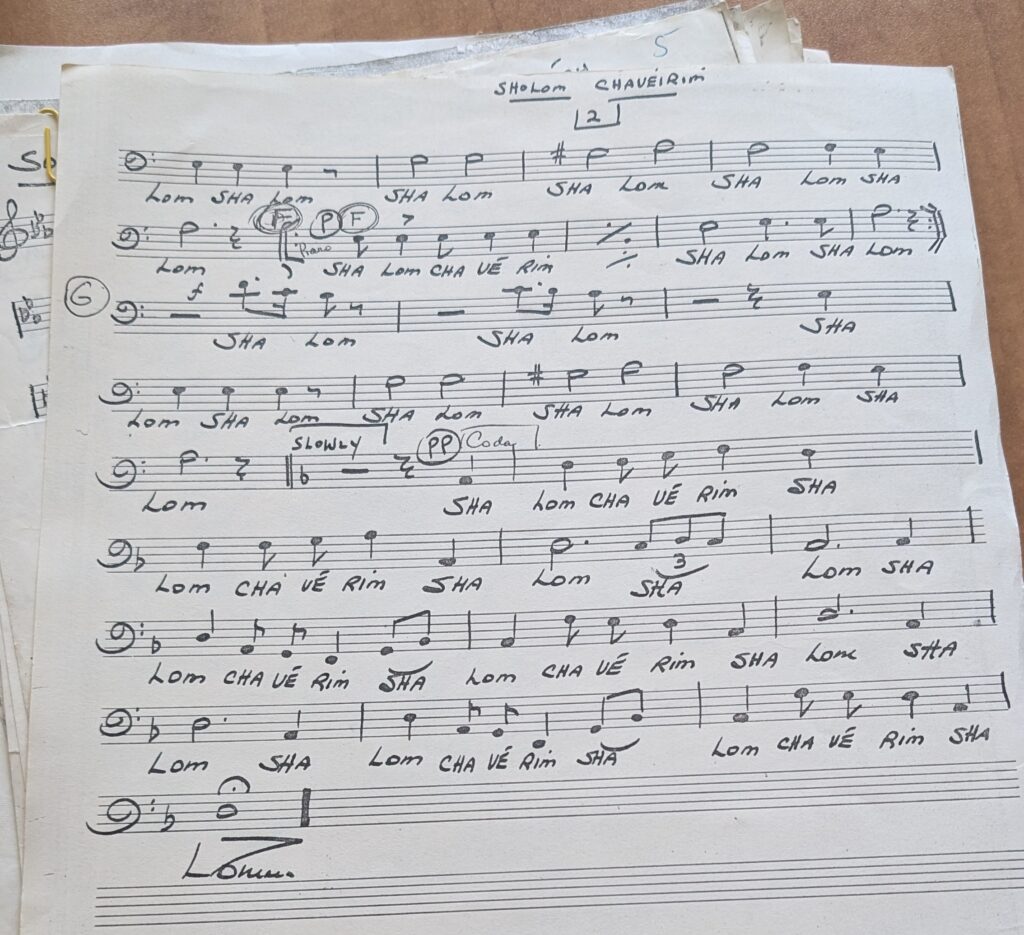

And maybe the same is true of Burko, but that’s… That seems weird, because in fact, that’s not the case. Because in the programs, it says accompanist so-and-so, it lists them off. A pianist who would have been playing along. So I’m not sure where those parts are, and I’m not sure how that you would recreate that, other than listening to the four-part Harmony, and then coming up with a new piano part. Which kind of makes the collection a little bit inaccessible, other than if you’re gonna sing everything a cappella. Which could be great, but I know from these, you know, from the programs that there were piano parts.

And I know from, the sort of commercial arrangements, the Octavos, or whatever they’re called, what are those things called? Octavos. Anyway, there’s a whole bunch of those, I think you took some of those commercially printed choral parts, which are sort of standard.

D. Yeah. Like, the ones from New York.

J. Yeah, so everybody’s got those, so… so that’s not particularly interesting about the collection.

Um, so we’ve got folk songs. Definitely, there’s a lot of Holocaust repertoire. Definitely there’s a lot of worker’s songs, like, Worker’s Circle kind of repertoire? And Bund songs. This other name that keeps coming up is [David] Botwinik. He’s another very cool story. His son [Alexander] is a musician and a choir director who just released a triple album of his father’s music. And he was also a synagogue conductor, this guy, Botwinik.

D. In Montreal, or…?

J. In Montreal. Really interesting guy, published a book of Holocaust songs, original Holocaust songs that he wrote. A very nice, very well put together book, because the son has been putting out stuff of his father’s. He just put out these records of children’s music. And so there’s a bunch of Botwinik stuff in here.

Um, there’s… I’m just, opening it and seeing, like, here’s a setting of Rokhl Korn, who’s a Montreal poet.

D. Yeah.

J. So that’s pretty cool, like, there’s original songs that have never been heard since, you know? And of our repertoire of, Montreal repertoire, Montreal poets, Montreal arrangers, Montreal choir.

But then there’s just standard repertoire. Rozhinke mit Mandlen, and you know, A Freylekhs. A Gneyve, but maybe a different melody, because it’s arranged by Eli Rubinstein. A Gleyzele Yash, Arum dem Fayer.

Um, this is what I’ve got so far. I think you saw this.

Josh gestures to a stack of scores clipped together in sets.

D. Yeah.

J. This is the songs, like… A to B, or aleph to whatever.

Josh then turns the camera to several large boxes of papers in the corner of the room.

J. And… and what I have in the corner there is unopened. Well, it’s not unopened, it is unsorted, or whatever. And I haven’t even really counted. I think I did start a chart, a chart of just the names of every song. I think I was up to, like. 110 or something so far.

D. Yeah. That’s good to know.

J. Yeah.

D. So you said, you sort of tried, shopping them around to see if anybody’s interested in taking it as an archive, and so far nobody’s super jumping at it?

J. I didn’t really… I haven’t yet done that at all. But one thing that I was curious about was the Jewish Public Library. They already took a bunch of stuff. But they’re always trying to not take stuff, because they don’t have room. But then when I showed them the choir materials and what it would look like once I’ve organized it into one sheet of each… like, just one page…

Josh gestures again to the stack of organized scores clipped together.

J. I think this is very doable for them. Once I get like, 3 times this, they can just put that in a corner of the Jewish Public Library, because they already do have quite a collection of the Worker’s Circle papers and stuff. But I’m also tempted to see about giving it to the McGill Music Library.

D. Right.

J. The Schulich [School of Music] at McGill, just because now I’m at McGill, and it’s at McGill, and the students are… will be going through it again next semester.

D. Yeah.

J. Real scholars could do some cool work on this collection. And if it’s in the Jewish Public Library, it’ll just be a little bit less accessible to anybody other than somebody looking at the Jewish community. But this could actually be useful for the Montreal music community, somehow.

And I’m sure some of these are kind of written-out versions of… Those commercial charts?

D. Yeah, I think you showed me a bit of that when I was there. So it’s like… it’s pretty close, it’s just, one line from it or something.

J. They’re just sort of written out. Yeah. So that’s also not that interesting, but…

Yeah, I’m curious about the state of, like, the Head Office Worker’s Circle choir, you know? Like, in New York City. Do they have all the original Maurice Rauch papers? I bet they do.

D. Good question.

Josh and I spent some time discussing the little we know about the interactions between the New York and Montreal Workers Circle organizations and how they seem to have been very isolated from one another.

D. Yeah. So I asked you what you would do with the papers, but also, what would you like to do with the musical content? You know, to restage it, or to put it out there. Do you know what I mean?

J. There’s been a lot of interest. Just whenever I talk to people about this, about starting a choir. So that would be kind of the easiest thing.

D. Yeah.

J. It wouldn’t be easy, but that would be a way to put this music to work. Whether it’s with McGill. Or if it’s just something in my apartment. And I’ve had a ton of people, old and young, be very interested in it: “oh, I’d love to join a Yiddish choir, sure.” And my students. This year, I’ve got twice as many students as last year. Somehow, it’s like, people are interested in this. And they’re telling each other…

Otherwise, what I’d really like to do, once I get to the bottom of the box, and I have a copy of each page. Then I will begin the next stage of… Of, like, turning this into an archive. Which will be digitizing. And making it available to the world. I guess, a website or affiliated with some other website?

Josh and I discussed various different organizations and institutions who were hosting content in the Yiddish music world.

D: It doesn’t hurt to have a Canadian organization doing it, too?

J. Or, it doesn’t have to. Yeah. Sure, if I could. I’m totally open… I have not yet explored or shopped around or seen who’s interested or not.

D. So, is there any type of Yiddish organization in Montreal now… what is there that is kinda equivalent to the Worker’s Circle?

J. I think there isn’t. There’s this… you know, have you met Eli [Benedict], the Israeli Hasidic Yiddish dance guy, he taught at Weimar this year?

D. No, I don’t think so.

J. Anyway, he’s this Hasidic guy. Funny dude, very passionate. He basically runs the Yung Yidish in Tel Aviv. You know that place with Mendy Cahan that is, like, in a bus station? It’s a kind of chaotic, but amazing space. So he runs that, and then he’s also doing one like that in Vienna. But now he has family in Montreal, so he just kind of started… He just basically took a bunch of stuff, I think, from the Worker’s Circle and from another place and put it all in a loft. That is looking like it’ll turn out to be a centre for this stuff. A lot of the books from the Worker’s Circle went there. Um… Shlomo and that crew are bringing stuff there. So at least it’s, like, young people that are interested and rocking it, but they have absolutely no resources at all. Like, it’s just… a piece of gum, like, sticking it all together.

D. Yeah.

J. Rocking it. But … they have meetings every week, and there’s stuff going on, and sing-alongs, and it’s like, it’s a new kind of scene. That’s not exactly the right place for this.

This could be anywhere, but also, once it’s digitized, it could be everywhere, so…

D. Let me just look up my questions from a while ago to see what else I haven’t asked you.

J. Okay. Okay.

D. I think I’ve pretty much covered my questions that I wrote months ago. How about: you talked about the themes, it’s a lot of folk songs and Holocaust and worker’s songs. So, I sort of remember there’s some Israeli stuff in the programs, at least. I don’t remember, but in the music. So when does it start having more Israeli stuff? Or was that always just a small part of it?

J. Um. Good question, and maybe we could… you could analyze the programs, I’ll send you… But also that would have been, probably, an influence by Rubinstein, who’d just come from Israel.

D. Yeah.

J. Yeah… you could also ask, maybe if you talk to Augenfeld. Kind of ask her about the evolution of the politics of the choir and the space. And just, what they were interested in, and how it became less about this, and more about that, sort of. Jewish identity in general, and that would include Israeli repertoire.

Also, maybe it reflected the guests they had. They always had guests. For each concert, they would have a soloist come in. Most of them were Yiddish-y early on… I mean, it’s total Yiddish stuff in the 50s and 60s. But then it gets to be more, probably, Israeli soloists and stuff. They would sing a Yiddish tune or two, maybe less Yiddish tunes.

But it’s definitely… yeah, no, I guess it’s mostly Yiddish, even up to the end. And not that much… Not that much Hebrew rep, to be honest.

D. Yeah…

J. Really mostly Yiddish rep. Mm-mm. It’s too bad about the piano… parts, though. I wonder where the hell that is. Now I have to track down the… accompanists, and then find their children, and then see if they have the papers of their parents who… kept all the papers of accompanying the Yiddish choir in 1952. I doubt it.

D. And it’s not in the Rubinstein archive in the [Jewish Public] library?

J. No, no. There’s, like, a folder of pictures of him at the theatre. And then a ton of his papers, but not really together, like, they just sort of go show by show. So, like, if he was the director of the show, okay, then you’ll get his score. But where are his papers? Where are his original songs? Where is… Great question.

J. Um, cool. Okay, I’m gonna… I gotta get to… Whew!

D. Yeah, I think we covered everything, yeah.