The Progressive Musical Benevolent Society was a mutual aid and burial society for New York City klezmer musicians and their families. It was founded in the early 1910s, hit its peak in the interwar and postwar years, and declined by the 1970s. It was formally dissolved in around 2010, but by then the remaining members hadn’t officially met in decades. While I was doing research at YIVO back in the spring, I took many photographs of the two collections they have about the P.M.B.S. These are RG 2110 Records of Progressive Musical Benevolent Society and RG 2330 Progressive Musical Benevolent Society Records. The first collection dates to the late 1970s and 1980s from the era when the organization was winding down its activities under the leadership of Jack Yablokoff, and was mainly about deaths, burials and payments. The second collection is mostly legal documents about dissolution of the organization in the early 2000s, but also contains a cemetery map.

The organization was founded in around 1911, following the model of the many landsmanshaftn and trades-based mutual aid societies in the immigrant Jewish world of New York’s Lower East Side. (The exact date is inconsistent; some say 1911, 1913 or 1914, or even 1921. I tend to believe 1911.) As with other such organizations, the P.M.B.S.’s function was to offer stability to its members by way of sick pay, burial rights in the organization’s cemetery plots, and other forms of support. And over time it seems to have taken on an important social role for New York’s klezmer musicians, in addition to some kind of professional function as a known source of said musicians.

Given that the YIVO records start in the mid-1970s, it means that there is a six-decade gap in documentation about the activities of the organization. I can’t find it at the moment, but I recall reading a facebook comment that Jack Yablokoff, when he took over as head of the P.M.B.S. in that era, wasn’t given any of the meeting minutes or documentation from before his time. If true, that is quite a loss as we know very little about the inner workings of the organization during its prime years. Bits and pieces of oral history from descendants of members are very helpful, but cannot replace the detailed, contemporaneous procedural information of the type YIVO has collected about many other mutual aid societies.

Because of the family backgrounds & professional activities of many of its members, I see my research into the P.M.B.S.’s activities as a window into the social, family & economic world of New York’s historical klezmer musicians outside the limited scope of the recording industry. Among its members were not only famous soloists like Naftule Brandwein and Shlumke Beckerman, but dozens of lesser known and forgotten musicians. Since getting back from NYC in May, I’ve been gradually working through YIVO’s materials on the P.M.B.S. and building up my understanding of the organization’s membership. This month I’ve been trying to sort through some of the fruits of this research in preparation to give a talk about it at KlezKanada’s Yiddish Culture Jam in Montreal at the end of February. Here’s where I’m at with my research at so far.

Membership of the P.M.B.S.

The total list of names I have associated with the P.M.B.S. comes to about 550 people. This is based on the cemetery maps at YIVO, 1970s ledgers and funeral slips at YIVO, names of donors inscribed on the two cemetery gates,* and a list of members from the 1970s held by Henry Sapoznik. Of those 550, I have identified roughly 125 as being members of the musician’s union A.F.M. local 802 during the period of 1922–1945. That number will probably continue to grow as I identify more of the members, but generally the wives of musicians were not union musicians and many of their children were not, either.

40 of the members I have identified as being ‘klezmer musicians’ in other sources, but the real proportion is probably much higher. Being a working musician for the Jewish community is not something that was well documented in memoirs or newspaper coverage, and rarely anyone but the bandleader got mentioned in advertisements! Plenty of others worked in other parts of the music business: vaudeville, restaurants, theatre and classical orchestras, and so on.

The oldest members were born in Europe in the 1850s and 1860s, but the majority of the musicians were born in the 1880s and 1890s. That makes sense for an organization of working people founded in 1911. The youngest musicians in my list were born in the 1910s, but many of the grandchildren of the original members were born throughout the 20th century and are still alive—for example, Dave Levitt, who has been very helpful to me in my research. The earliest deaths I could find were of Samuel Klotzman in 1919—the infant son of Łódź-born drummer Abraham Klotzman—and the musician Joseph Machnowetsky, who died in 1920 and about whom I know almost nothing so far.

Even if I eventually work my way through all the names in the cemetery maps and other lists, it’ll still be missing some names. This is because P.M.B.S. was a dues-paying organization which could expel delinquent members, as did all mutual aid societies of the time. Members could also pay dues for a time, but move back to Europe, or to Florida or California or elsewhere in the United States, and drop out of the organization and be buried locally. For example, Abraham Klotzman, who I mentioned above, seems to have left the organization by the 1930s when he died and was buried elsewhere.

Unless by some miracle the meeting minutes and ledgers from earlier eras resurface one day, I’ll have to make do. But the cemetery lists are still invaluable, as the people buried there show the trajectory of klezmer families over the course of the 20th century.

*The names on the two cemetery gates, erected in 1923 and 1939, contain a subset of names who were NY musicians who were not buried in either P.M.B.S. plot, but were definitely buried somewhere else with a landsmanshaft or some other society, such as Klotzman. Hard to say if all of these were members who left later on, or simply well-wishers who wanted to make a financial gesture to their fellow klezmorim.

The P.M.B.S. didn’t leave much of a public trace

Many Jewish immigrant mutual aid societies founded at around the same time advertised their social events in the Yiddish press and their activities were occasionally covered in short articles. The purpose of this was to invite in landsleit from nearby areas who were also in New York, and to attract new members, etc. They also sought to attract donors for their charitable projects, such as the construction of a hospital, study house or factory back home. But so far I haven’t been able to find any trace of the P.M.B.S. in Yiddish or English press archives, or being mentioned in old memoirs or music history books (except very recent ones). It doesn’t help that the name of the organization is made up of such common words; it’s much easier to do a targeted keyword search for Chotiner or Podolier than it is for Musical or Progressive.

Some of the other historical mutual aid societies didn’t leave much of a trace either. It isn’t unique to the P.M.B.S. While some sought to recruit strangers or to fraternize with their landsleit, others don’t seem to have advertised or left much of a trace beyond their cemetery plots. This is true, for example, of the society Abe Elenkrig, his family, and Meyer Kanewsky were members of, the Zolotonosher Friends. The cemetery section is there, and some paper ephemera were kept and digitized by descendants, but almost nothing has been printed publicly about it.

Not all NY klezmorim were members

There seems to have been a natural upper limit to the size of immigrant Jewish mutual aid societies in New York. This is why we see a long list of landsmanshaftn for immigrants from large cities or populous regions (such as Warsaw or Bessarabia). The existence of several ‘competing’ mutual aid societies was not always because of ideological or personal schisms, although that also happened. In fact, many of the landsmanshaftn from the same place got along well and would band together for charitable projects or to throw a big party. It’s just that the management of services by an elected board probably became too complicated once it involved hundreds of members. This is why I doubt the P.M.B.S. was trying to expand to gain some kind of monopoly over immigrant Jewish musicians in New York. There were simply far too many of them, and many already belonged to landsmanshaftn or other societies.

I will preface this list with a caveat that I’m only guessing these people were not members, because they weren’t buried in the P.M.B.S.’s plot and didn’t show up on any lists. Maybe they were at some point during its history.

Dave Tarras, the celebrity clarinetist, was the most famous NY klezmer to have not been a member. Many other recording artists of klezmer’s golden age weren’t either: Abe Schwartz, Max Yankowitz, Max Leibowitz, and Joseph Moskowitz, Israel J. Hochman, Abe Katzman, Beresh Katz, Joseph Frankel, Abe Elenkrig, Jacob Gegna, and so on. Same goes for many of the bandleaders I’ve been researching who were playing for the Jewish community back then: Joe Magaziner (1886–1971), Max Ausfresser (1880–1941), Max Ellenson (1878–19??), Aaron Greenspan (1881–1938), etc. The big Yiddish Theatre bandleaders and arrangers, who sometimes had one foot in the klezmer world, weren’t either: Abe Ellstein, Joseph Cherniavsky, Alexander Olshanetsky, Joseph Rumshinsky, and so on. With some large musician families like the Brandweins, Radermans, Beckermans and Fiedels, some of them were members and others weren’t.

As I said above, its most famous member to klezmer fans was surely Naftule Brandwein, as was his contemporary Shlumke Beckerman. Abraham Constantine (1891–1953), a cornetist who played on some classic recordings, was a member, as was trombonist Isidor Drutin (1884–1954). Probably all of the Epstein Brothers were, as were several of the Fiedel family, although I’m not sure about cornetist Alex Fiedel (1886–1957) who we know from old recordings. Some of the Rapfogel brothers, Galician-born musicians who seem to have worked with Israel J. Hochman, were members, as well as Jack and Marty Levitt. Harry Raderman (1897–1947), a drummer and not the famous jazz trombone player, was a member, as was Hyman Millrad (1882–1971), a composer and bassist who appears on many old recordings. Several members of the Grupp family, who were related to Alter Chudnover back home, were members as well. And from there we can add a long list of other musicians and their families, musicians who were small-time klezmer bandleaders, or sidemen, or played in all kinds of other parts of the music industry over time.

I’ve found it interesting to explore; in filling out the family tree of P.M.B.S. members, I realize that someone is related to a non-member I know from my klezmer research. For example, bandleaders & klezmers Leopold Zimbler (1853–1939), Sigmund Goldring (1888–1947) and Samuel Frankfort (1870–1956) all had children who were buried in P.M.B.S. cemetery sections, even if the fathers were buried elsewhere. Frankfort’s daughter Dora married into the aforementioned Fiedel family, so that both sides were connected to the P.M.B.S./klezmer circles.

Romanians were poorly represented in the P.M.B.S.

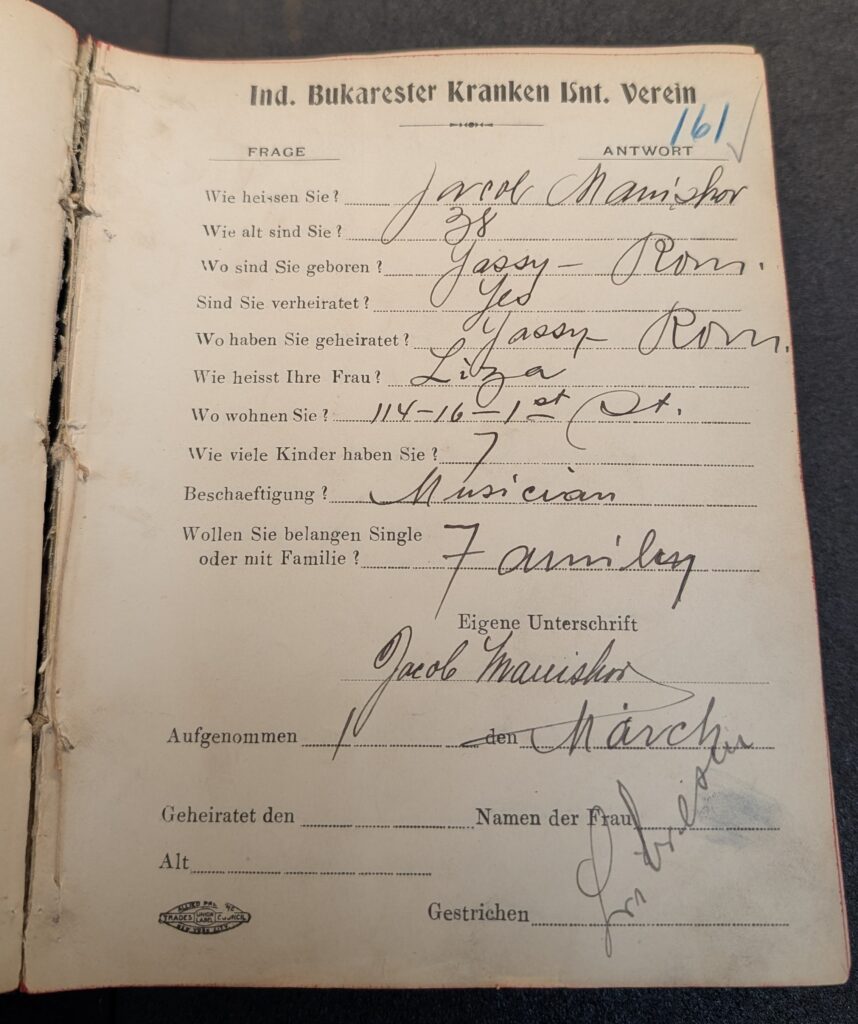

Romanian Jewish immigrants to New York City were far fewer in number than those from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. But they were over-represented among golden age klezmer recording artists: Joseph Moskowitz, Max Leibowitz, Abe Schwartz and Max Yankowitz were all Romanians, as were some notable klezmer bandleaders who didn’t record, such as Jacob Manishor (1865–1950). None of those musicians were members of the P.M.B.S., as far as I know. While I will probably find some eventually, I have yet to identify any Romanian-born musician members of the Society! Although there are some Bessarabians, who in cultural terms are of course closely connected to Romania.

So far, I would say two thirds of the musicians were from all parts of the Pale of Settlement (that is, the western Russian Empire), one sixth from Austria-Hungary, and one sixth American-born. Maybe the proportions will shift as I continue to investigate members on the list, but probably not by much.

Links between the P.M.B.S. and musicians’ unions are interesting

Finally, there are some interesting and notable connections between the P.M.B.S. and the music unions operating in New York. The earliest Jewish music union was founded in 1889 as part of an expansion of the United Hebrew Trades-affiliated locals; the Rusishe Progresiv Muzikal Yunyon No.1 fun Amerike, which James Loeffler wrote about in the linked article. It mainly represented Yiddish-speaking klezmer musicians. Loeffler suggests that the remnants of that union were incorporated into the P.M.B.S. in 1921 after A.F.M. local 802 to gained a monopoly over union musicians in New York. I’m unclear on the relationship between the functions and memberships of the Russian Progressive Musical Union and the P.M.B.S., but hopefully I will sort some of that out in my future research.

In the first decades of the 20th century, the A.F.M. affiliated union local 310 gained members and tried to pressure the U.H.T. affiliated music union to cease operating. I’m also unclear on the exact nature of that dispute, but it shows up in some A.F.M. conference discussions. Over the course of the 1910s, plenty of P.M.B.S. members joined local 310, whether after leaving the U.H.T. union or from being non-union. Each newly joined member was announced in International Musician magazine, so it’s easy enough to track.

Others probably worked as non-union musicians for very niche landsleit gigs; in his oral history with Henry Sapoznik, P.M.B.S. member Louis Grupp said that it sometimes took a few years of performing for weddings and simchas among their landsleit before musicians even joined a union. By the time local 310 was refounded as local 802 in around 1922, most of the P.M.B.S. members who were out regularly working in public should probably have been members of it. There were exceptions here and there, but it was frowned upon and would probably get someone in trouble eventually.

A few P.M.B.S. members were elected to notable roles in local 802 as well. (See The History of Local 802 on the union’s own website.) The best known among these was Max L. Arons (1904–1984). After rising through the ranks of elected roles starting in the 1930s, he became president of the union in 1965, a title he held until 1982. During the same time period, P.M.B.S. member Al Knopf also rose as high as Vice President of the union. Others worked in more humble roles; vaudeville drummer Jack Zimbler (1891–1965) and his sister, the cellist Mathilda Zimbler (1897–1990), children of Leopold Zimbler who I mentioned above, worked as clerks for local 802 in the 1940s–50s.

Conclusion

I’m still working through the materials I have about the Progressive Musical Benevolent Society, and hoping to find new angles into the history of this organization in 2026. Perhaps some printed materials about it are sitting somewhere in a box of a family member. But if I can’t find anything else, seeing the family and professional connections between the members of this fascinating organization has been leading me down all kinds of interesting research paths. Most likely, my talk in February will focus on the basic function of the organization and a who’s-who of some interesting members and what they got up to.