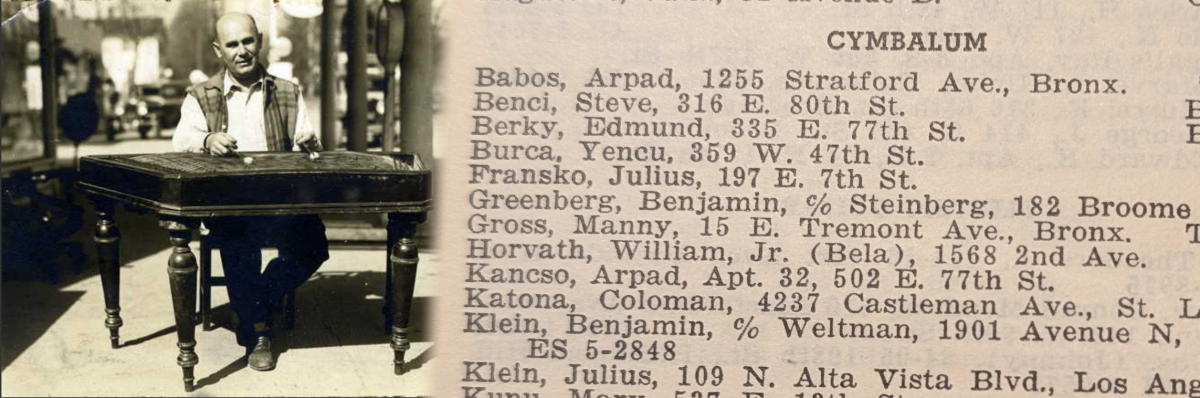

While I was in New York this spring, I visited the Tamiment Library at NYU and photographed a lot of American Federation of Musicians Local 802 directories, of which they have an impressive collection starting in 1922. The directories list all the active musicians in the New York area by year, which instrument they play, and their home address.

As a cimbalom player, I was naturally curious about which names would be listed under that instrument. In most of the years between 1922 and 1950 there were between 25 and 35 union cymbalists, with a mix of Jewish, Hungarian, Slovak, and a few Greek names. Some names came and went as older players passed on or moved away, and younger ones started working in New York.

Here is what I was able to figure out about the Jewish cimbalists in the local 802 directory. Keep in mind that many or most of these did not necessarily play ‘klezmer’ music most of the time or at all.

Joseph Moskowitz (1875–1954)

Joseph Moskowitz is probably the only Jewish-American cimbalist most 21st century klezmer fans could name. I’ve mentioned him on this blog before as he’s been a longstanding interest and influence on my playing. I won’t go into his biography in depth since it’s already covered on his Wikipedia page. Born in Galați, Romania in 1875, he seems to be the oldest of these local 802 cimbalists. Although he was active in New York since before WWI, he only appears in local 802 directories after 1929. From then he appears in most years up to 1941, when he was living in Akron, Ohio, and 1945–50 when he was living in Washington, D.C.

He died in Washington in 1954. See this page Remembering Joseph Moskowitz.

Samuel Greenberg (c.1880–1927)

After Moskowitz, Samuel Greenberg seems to have been the oldest of the Jewish cimbalists in local 802. He was born in Sniatyn, Galicia, in around 1880. This town was on the border with Bukovina; JewishGen has a page about its Jewish history. He was from a Yiddish and German speaking family. They seem to have emigrated together to New York in the late 1880s, but I was not able to find any trace of them until 1902 when Sam was living in the East Village. In that year Sam married Lucille Thérèse Dreyfus, who was born in NY and was the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine.

By 1905 he was living on East 51st in Manhattan along with Lucille and his brother Isidore, a violinist. Both brothers gave their occupation as “Musician, Hotel” in the 1910 census. By the 1920 census they were living in the Bronx; Samuel still worked as a hotel musician while his brother Isidore worked as a theatre musician, alongside his brother-in-law Samuel Mendelsohn, a drummer and fellow Galician immigrant who lived with him.

I couldn’t find anything about Samuel’s cimbalom playing outside the union directories. When local 802 was founded in the early 1920s, Samuel appears as a union cimbalist in the first directory (1922–23). He appeared for the next few years until 1927. In September of that year he contracted Bronchopneumonia and was hospitalized for a few weeks before passing away in early October. His brother Isidor also died in 1925; both died fairly young. They were buried in the Sniatyner landsmanshaft plot at Mt. Zion cemetery, as were the other relatives mentioned above.

Samuel Nusbaum (1882–1946)

Sam Nusbaum (sometimes spelled Nussbaum) was born in Lemberg (Lviv), Galicia in 1882. Like Sam Greenberg, he seems to be one of the few Galician Jewish cimbalists we know about from New York. Sam’s father Manny (Menashe) had passed away by 1910 when I found the first trace of Sam in the Census; his mother was called Mollie. By 1910 Sam already listed his occupation as a theater musician. I’m not sure what he was doing in the 1910s; there was also a violinist in NY with the same name, so I can’t say which one the various references to a vaudeville or novelty musician Sam Nussbaum refers to.

By 1920 Sam’s first wife had passed away and he remarried to someone named Regina Nudel. At the time he was still living on Attorney St. in the L.E.S. It’s in the 1920s that he starts to appear more clearly in the press as a touring solo artist. He toured New York state with various other singers and violinists in the winter of 1923–24.

The above two articles mention Nusbaum’s involvement with the Moscow Art Theater and the Pienele Musical Bureau in New York, about which I couldn’t find any more information. In the following February he toured with violinist Natasha Jacobs.

After that tour, I was unable to find any more newspaper coverage of his concerts. However, he remained a member of local 802 until at least 1943. In the 1940 census he gave his occupation as “Proprietor, Candy Store.”

He was diagnosed with cancer and was checked into the N.Y.C Cancer Institute in Manhattan in early 1946; he died there three months later.

Emmanuel “Manny” Gross (1883–1952)

Manny Gross was born in Hungary. I didn’t find any documents more specific than that in a quick search of Ancestry and FamilySearch—possibly in Sátoraljaújhely? His father, Joseph Gross, born c.1856 and also a musician, and his mother was called Clara Gelb. The whole family immigrated to New York in around 1889. During that time, I think he was still going by the name Isidor. By the time I locate him in the 1900 census, he’s living with the family on Avenue B and already working as a musician.

He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1914 and in 1915 got married to fellow Hungarian immigrant Ella Prince. On his WWI draft card he gave his place of employment as Klaw & Erlanger‘s New Amsterdam Theatre. The first mention I found of him in the press was talk of him as a soloist in an October 1916 People’s Symphony Concert at Carnegie Hall. Paul Gifford, author of The Hammered Dulcimer: a history, also mentioned that he believes Gross recorded two discs for Edison in 1916 as M. Nagy (the Hungarian version of his name).

In 1929 he played with Emery Deutsch’s “Gypsy Camp” orchestra on WABC (you can hear plenty of Deutsch’s recordings from the era on Internet Archive, though I’m not sure if Gross played on them). And in 1930 he resurfaces as a soloist playing Hungarian music in a nationally broadcast radio program Jack Frost’s Melody Moments, directed by violinist Eugene Ormandy.

By that time he was living in the Bronx. In the 1940 census he gave his occupation as “Musician, Club” and in 1950 “Musician, Orchestra.” He was also listed as a cimbalist in the local 802 directories for the entire run of years I was able to view (1922–1950). He died in the Bronx in February 1952.

Benjamin Greenberg (1883–1944)

Benjamin Greenberg is another obscure figure who was apparently a piano and cimbalom player in restaurants in New York between 1903 and the 1940s. He wasn’t related to Samuel Greenberg as far as I know. Born in Galați, the same small Romanian city as Joseph Moskowitz, he arrived in New York in 1903.

In 1905 Benjamin married Bella Kasser, another recent immigrant who was born in Grodno. What’s interesting is that one of the witnesses to their marriage was Rubin Popik, a small-time Yiddish actor born in Istanbul who recorded a few 78 rpm discs for the Rex Talking Machine Company in Philadelphia during WWI. After the war, Popik went into the restaurant business and owned various restaurants and nightclubs into the 1940s.

In the 1910 census Benjamin indicated his occupation as “Musician, Piano” and in 1920 as “Musician, Restaurant.” On the 1930 census he said “Musician, Theatre.” As far as I can tell, of all of Benjamin’s children, only Ida/Yetta (born 1906 in NYC) became a professional musician (a pianist).

Strangely, I can’t find Benjamin in the local 802 directory in the 1920s. He appears as a cimbalom player in the 1931 directory and continues to appear most years until 1943. On his WWII draft card he indicated that he was employed by Markowitz & Kessler’s restaurant at 220 Eldridge Street. We can see it from the street on this 1939 tax photo.

Benjamin died in December 1944. He was buried in the Mount Judah Cemetery in Ridgewood, N.Y.

Julius Kessler (1884–1964)

Julius Kessler is another cimbalist whose music career remains fairly obscure. He was born in New York in 1884 into a Hungarian Jewish family; his mother Kate (Katti Prince) immigrated shortly before his birth with his older brother Harry (b.1882). I wasn’t able to find any trace of their father Michael Kessler in the US. By 1900, when I found him in the census, Julius and Harry were already working as musicians, with Julius listed as a “Cymbolist” in the 1910 census. He listed his occupation during WWI as being a musician at Cohan’s Theater at Broadway and 43rd Street. At around the same time he seems to have run a musical instrument store; I found an advertisement for it from 1917.

Kessler continued to be a union musician and appeared in the local 802 directory as a cimbalist between 1922 and 1925, after which he disappears from the directory. Unlike some of his contemporaries, I was not able to find newspaper coverage of any solo concerts of his.

In the mid 1920s, Kessler left New York and, as far as I can tell, professional cimbalom playing. He settled in Bushkill, Pennsylvania and opened a general store. Over time it expanded into being a soda parlor, restaurant and adjacent gas station; he also ran a vacation rental cottage business. He died in Bushkill in 1964.

Julius Klein (c.1887–1966)

Although his name may not mean much to my readers here, Julius Klein was certainly the most famous of all these cimbalists. Like Gross, he was born in Hungary in the 1880s, though I wasn’t able to find out exactly where (one newspaper biography suggests Budapest). His family immigrated to New York when he was only an infant. His father, Bernard Klein, was also a musician; his mother was called Dora (Neiderman?). Several of his brothers would become musicians in New York: Benjamin (b.1891, cimbalom), Louis (b. c.1899, drummer), David “Daniel” (b. c.1902, saxophone), etc.

By the 1900 census the Kleins are living on Attorney Street in the L.E.S. By the 1905 census Julius is working as a musician, and is listed in the 1910 census as “Musician, Cymbal.” In 1908 he married fellow Hungarian immigrant Rose Rosenberg. By 1920 he had relocated to the Bronx and was listed as a hotel musician. He appears as a local 802 cimbalist for essentially the entire run of directories I had access to, from 1922 to 1950. Paul Gifford informed me that Klein recorded some 1920 discs as Kiss Gyula (the Hungarian version of his name) accompanying the tarogato player Gyula Dandás, and that he also recorded with Paul Whiteman.

However, being described as an accompanist or hotel musician underplays the level of his fame; in the Lower East Side, Atlantic City and farther afield, he played for the ultra wealthy, for celebrities, and politicians. See this article about him from the Daily News in 1935 going over some of his celebrity fans:

He moved to the west coast during Prohibition, initially settling at Agua Caliente near Tijuana before Baron Long brought him to Los Angeles in 1934 to play at the newly reopened Biltmore Hotel. (I’m not sure of the exact timeline, as he continued to claim residence in the Bronx until he was living in Los Angeles.)

Playing in California in the 1930s, Klein continued to attract the attention of celebrities; a number of newspaper photos show him posing with his cimbalom and a variety of figures.

You can see him playing a bit in a Hungarian restaurant scene in the 1945 film The Dolly Sisters, about 2 minutes into the film. Per IMDB he also appears uncredited in Golden Earrings (1947), Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1942, playing solo near the start after 1:30) and The Mask of Dimitrios (1944).

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s he continued to play in California restaurants and casinos, and also in Las Vegas and elsewhere.

Here is another profile of Klein from 1957:

Newspaper mentions of Klein became scarce in the early 1960s; I’m not sure if he retired or just became less of an object of interest. He died in Hollywood in 1966. Members of his family continued to be notable in the LA music world; his son Harold (b.1910) was a violinist and his great grandson Dave Klein was the drummer in punk band Agent Orange during the 2010s.

Benjamin Klein (1891–1968)

Benjamin Klein was Julius’ less famous cimbalist brother who was born in New York a few years after the family arrived. On his WWI draft card he is living in the Bronx and lists his occupation as “Musician, not employed at present.” In the 1920 census he is living in Philadelphia and appears with the occupation “Musician, Orchestra.” According to that census he was then married to a Russian Jewish immigrant named Martha and they had a young son called Arthur.

By the early 1920s he moved back to Brooklyn and settled in the same house with several of his musician brothers. This is where he appears as a local 802 cimbalist in the 1922 directory.

We can see one of the Klein brothers here (it’s unclear which) being quoted in an article about men’s fashion:

In the 1930 census he is listed as a theatre musician. At this time he was still living in Brooklyn. In 1933 he remarried to Genevieve Piechocki. He continued to appear in local 802 directories as a cimbalist although I was not able to discover much about what he was doing. He died in 1968 and was buried along with most of the Kleins in the Mount Zion Cemetery in Queens.

Helen Borsody-Sdoia (1895–1975)

Helen Borsody was one of the few Jewish women cimbalists of this era, although a fairly obscure figure. She was born in Hungary in 1895; her family seems to have immigrated to New York the year after, although on some censuses they later gave the year as 1901. Her father, Morris William Borsody, was a violinist, and her mother was called Rose. Her brother, Emil Borsody, became a cellist. Coverage of Helen’s musical activities is quite scarce; the only newspaper mention I could find was this classified ad she took out seeking a “lady drummer and lady ‘cellist” in 1915:

In the 1920 census Helen gave her occupation as “Clerk” and in 1930 “Bookkeeper, Office.” However, she was also a union musician and appears in the first (1922) local 802 directory as a cimbalist, continuing to appear there (living variously in Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx) for the next 4 decades.

She married a non-Jewish man Candido Sdoia in 1928. Their daughter Phyllis Sdoia-Satz became a music educator and writer. Helen died in New York in 1975.

Honourable Mentions

There are three other cimbalists in the local 802 directories (and one not in it) who I considered including.

Antoinette “Toni” Steiner-Koves (1918–2007), being of a younger generation than the above cimbalists, appears only in the last of the local 802 directories I had access to, the 1950 issue. A relative made a website dedicated to her. She was an interesting figure who was very active in promoting the instrument in the postwar era. I’m not actually sure if she was Jewish or not.

Herschel “Harry” Sacher (c.1890-1970?) does appear in the local 802 directories during this entire period, but as a bassist. Born in Dobromyl, Galicia, he could play bass, cello, and cimbalom. He recorded a single disc for Edison Records playing cimbalom in 1925 (Only One Vienna, March and Through Battle to Victory, March). He appears in the press playing cimbalom concerts at various times over the years: in the People’s Symphony Concert, honoring Liszt’s centenary in October 1911, and touring with Sigmund Romberg’s band in 1949.

Ladislas or László Kun (1870–1939) appears as a local 802 cimbalist during the 1920s and 1930s and was an interesting and well-documented figure. I’m also not sure if he was Jewish; I suspect not, but a few people I spoke with thought so. He was a child prodigy on the cimbalom back in Hungary and became a teacher, performer and composer. He immigrated to New York in 1921 and continued to work as a soloist, composer, arranger and conductor.

Regina Spielman (née Szigeti, 1885–1966), born in Máramarossziget, seems to have been the sister of violinist Joseph Szigeti or at least a relative. She married a violinist called Solomon Spielman, and they immigrated to New York in 1923, although as far as I can tell she never became a local 802 member. (Her husband did.) They played as a trio on WEAF radio in 1924 with pianist Louis Spielman (presumably another relative). Solomon died fairly young, in 1930, and as far as I can tell they never had children.

She died in the Bronx in 1966. I find her matching gravestones with her husband, complete with stylized violin and cimbalom, rather touching.

That’s it so far. There are other old New York Jewish cimbalist names floating around but local 802 membership feels like a pretty good indicator of active players. Feel free to pass along any info you have about these or any other old New York cimbalists. Thanks to Paul Gifford who has been researching some of these figures for much longer than me and helped me fill in some gaps.